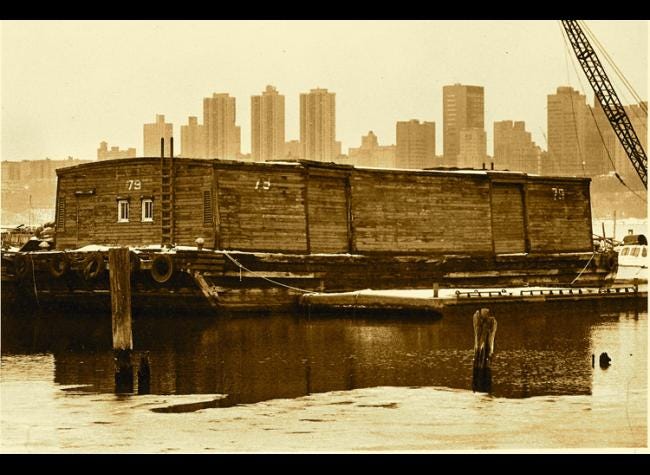

They were there before we were, by which I mean the cats were, before I moved in. I bought half of an old Pennsylvania Railroad barge on the Hudson River in the spring of 1971. The thing was at least 120 feet long and 30 feet wide. I bought my half from an actor who was rehearsing for a role in one of the productions of Shakespeare in the Park that summer. We were supposed to pay $50 a month dock fee to the mob, but they never showed up to collect, so after paying for the barge, we lived there for free.

The barge was tied up to a deteriorated dock on River Road in New Jersey. Technically, the barge was in West New York, one of the little Hudson County towns that lined the river, but the community, such as it was, along River Road at the bottom of the palisades was a world unto itself in those days. There was an old diner just downriver from the dock, and a few factories left over from the industrial boom along the river during World War II. Hardly anyone lived down there on the river. There were no houses, no apartment complexes like there are now – nothing, really, but landfill from illegal dumping that had occurred down there over the years – stacks of old wooden pallets, rusting truck carcasses, heaps of rotting plasterboard…the detritus of a world that once was.

The guy who sold me half the barge – for $500 in cash, a fortune in those days – had fixed up his half, but my end of the barge, the one that looked straight across the river at the 79th Street Boat Basin and downriver all the way to the Statue of Liberty, was raw space. It was sold as unoccupied, but I quickly discovered that wasn’t the case. A cat was living there, a big black cat with white markings on his face and white feet, and the first day I crossed the gangplank and opened the door to the barge, he was standing there looking at me, like, who the hell are you, Jack?

I checked with the guy on the other end of the barge to see if he owned the cat, and he said something like, “Oh, he’s just one of the river cats, there’s a few of them around. Be nice to them. They protect the barge from the rats.”

I soon discovered the rats he referred to were known along the river as Norwegian river rats, said to have escaped a ship from Norway decades, even hundreds of years before, and taken up residence along the Hudson. They were enormous things, nearly the size of a cat, with longer tails than rats I had seen going in and out of my building on Ave. B on the Lower East Side, which I had fled for the barge after a spate of robberies denuded five apartments on my floor of the occupants’ every possession, down to and including bathroom towels and kitchen implements.

The rats appeared to have extra-long snouts, too, and they swam in the waters around the barge like otters, diving and swimming great distances underwater every time they spied one of the barge cats patrolling the gunwales of the barge.

We were indeed dependent on the cats to keep us safe from the rats, who were said to carry rabies and God-only-knew whatever other diseases. Or maybe the whole diseased-rat thing was just prejudice against nosy rodents who were capable of cleaning out the kitchen of everything edible in a matter of minutes if the cats for some reason dropped their guard, which they did only once while I lived there on a day when Weird – that was the name I gave the big male cat after I had observed him for a few days – went on one of his occasional forays upriver to Edgewater where an ex-longshoreman I met told me he had a second family.

See what I mean about a separate world along the river? In a matter of a few weeks, I became acquainted with several former longshoremen and shad fishermen who had a makeshift marina upriver near the George Washington Bridge. Apparently, Weird had once lived there and had moved downriver in the last year or so, or so the old guys said. One of them seemed to know the family history of a dozen or more river cats who lived between West New York and Edgewater. Weird had been the alpha cat at their marina until an enormous yellow cat made his way down the palisades from Fort Lee and ran Weird off and took up residence with what had been Weird’s family of two females and an evolving number of kittens.

I was surprised and more than a little pleased when one night not long after I took up residence on the barge and had set up my typewriter and was working on a story for the Voice, Weird hopped up on the desk and strolled over and flopped onto the keyboard and promptly went to sleep. I had a little Olivetti Lettra 22, a portable that was about as flat as a typewriter could get in those days, the mid-century equivalent of a laptop, I guess you could say. Weird’s body covered the entire machine -- its keyboard and carriage buried in fur -- so I stopped writing and ran my hand along his side and scratched him behind his ears. He immediately started purring loudly.

I had never had a cat before, so I was just copying what I had done with the dog I grew up with, Chute, a dachshund we got when my father was stationed in Germany in the mid-50’s. It turned out that dogs and cats pretty much liked the same things, scratching and rubbing bellies and so forth, except cats purred, apparently as a way to encourage you to keep going with the affection.

Until that moment, I had never gotten close enough to pet either Weird or the female cat who lived there, who I came to call Big Gray. The decision to approach me, and indeed occupy the one spot in the barge I spent a good deal of my time other than in the kitchen, was his. Weird and Big Gray lived there. The barge was theirs before it became mine, and so was the waterfront and the river. They knew the river. They knew its currents and its moods and its delights and its dangers far better than I ever would.

I’ll give you a good example. Several months after my friend and classmate David Vaught arrived on the barge to help build-out the bathroom and bedrooms and attend NYU Law School, I was up on the roof installing a skylight where one of the hatches had been when David climbed up the ladder on the fantail and called to me. “Lucian, get your ass down here. You have got to see this.”

Big Gray had recently crawled into the sock drawer in my dresser and had deposited a litter of eight kittens. We had watched, fascinated, as she fed them and cleaned them and after their eyes opened, carried them around the barge, seemingly introducing them to their surroundings. I climbed down the ladder and followed David into my bedroom and stood there watching as Big Gray carried a kitten in her mouth over to a little hole in the wall in the kitchen where electric and water lines came into the barge. She went through the hole with the kitten in her mouth and promptly dropped her down the side of the barge into the river. Then she jumped into water after her and using her nose, guided the kitten over to one of the pilings and pushed her until the kitten got the message and grabbed onto the piling with her claws and climbed up.

Big Gray followed her up the piling and went straight back to the drawer and retrieved another kitten and did exactly the same thing. She was a river cat, and she was teaching her young ones how to survive life on a river that on the outgoing tide ran more than five miles an hour into the bay.

All the cats could swim. There was always the chance of losing their footing and falling in, but they needed to know how to swim for another important reason. Every time they would chase rats, the rats would dive into the water and the cats would dive in right after them. The landfill was several hundred feet away at the end of the broken-down dock, so the rats ran along the dock when they could, and when the cats would get wind of them, into the water both the rats and the cats would go.

Chasing rats was primarily Weird’s job. He was fond of perching atop a piling that rose about 10 feet above the surface of the dock, and when he saw a rat, he would launch himself from his perch attempting to land atop the rat but always missing. Apparently, even when they were facing away from Weird, they could detect him coming through the air and away they would go into the water with Weird following.

Weird would always come back into the barge and take a place on one of the rugs or, in the winter, under the potbellied stove we used to heat the place, and lick himself dry. David and I used to think we could see embarrassment on his face, that once again he had missed his mark and a rat had gotten away, but of course what we were experiencing for the first time – neither of us had ever had a cat – was humanizing the animal, reading into his behavior what would have been our own instincts or reactions had we been cats. Which was ridiculous but enormously entertaining as a trade-off between species. Weird took care of us by keeping the rats away, and we took care of him and Big Gray and the kittens by feeding them and giving them a warm, dry place to live, especially in winter, when temperatures plunged to single digits and the wind blew down the Hudson like an icy, invisible freight train.

The other cross-species thing we delighted in was coming up with words to describe cat behavior we were just becoming acquainted with. David was the master-name-giver for cat stuff. When the cats would take up a comfy spot somewhere and fold their front paws under their chests, David called it “tucking in.” Weird had a way of snapping his tail straight up in the air when on the prowl for rats, which became known as “dock-tailing.” When the cats would rub up against our legs or climb into our laps and turn upside down looking for attention, we called it “mongling,” for some long-forgotten reason. When they would scamper across the barge’s thick-beamed floors chasing real or imaginary dust-balls, they were “thundering.” We even named the position they took when curling up as “head-twist” because of the unique (to us) way they cranked their necks into seemingly impossible positions to get even more comfortable. And of course, when they would climb into our beds in the winter to spend the night atop our electric blankets, it became known as “coze,” short for the cozy spaces they created around our legs and feet.

Life on the river for humans after a year and a half of storms and thrashing waves and stifling heat and freezing cold became more than we could take. David moved back home and entered Southern Illinois University Law School, and I found the loft at 124 West Houston Street, and we left the barge without even looking to sell my half. The kittens had been given away one by one to visitors, and I took Weird and Big Gray with me to the city. Big Gray adapted readily to life in a Soho loft as big as the barge, but not Weird. Right from the start, as I was working on the loft building some walls and tiling kitchen counters, Weird would sit in the open front windows looking west down Houston Street with his nose in the air. When the wind was right, coming from the west nearly every day, I could smell the river, and if I could, I knew for sure that’s what Weird was doing.

Who knew how old he was, but he had been a river cat for his entire life, and it was sad seeing him sitting in the window and moping around the loft with nothing to do. So, one day I picked him up and carried him downstairs to the car and we drove over to River Road, and out there at the end of the dock where his tall piling stood in the sun, I let him go. He sniffed the air and took off without a look back. There were river rats that needed chasing, and if the old longshoreman was right, there was another family upriver in Edgewater he could take back if he could fight off the big yellow cat.

As I watched him lope down the dock, there was little doubt in my mind that Weird would at least give it a try. It was his world, not mine. He lived there on the river. I had been just a visitor.

Great story. I've been a cat guy all my life because their habits mimic mine. They don't try to engratiate themselves like dogs, and they're cleaner and more self-sufficient. And the don't bark when the doorbell rings.

The part about the kittens in your sock drawer made me remember the time when I was about 9 years old and my mom woke me up in the middle of the night to show me that our cat, Pussums, had had her litter of kittens on my bed, right between my legs, while I slept spread-eagled.

Your story was a welcome addition to my day!