Dirt, smoke, fire and steel

The ear-splitting thunderous wonder of dirt track racing in America

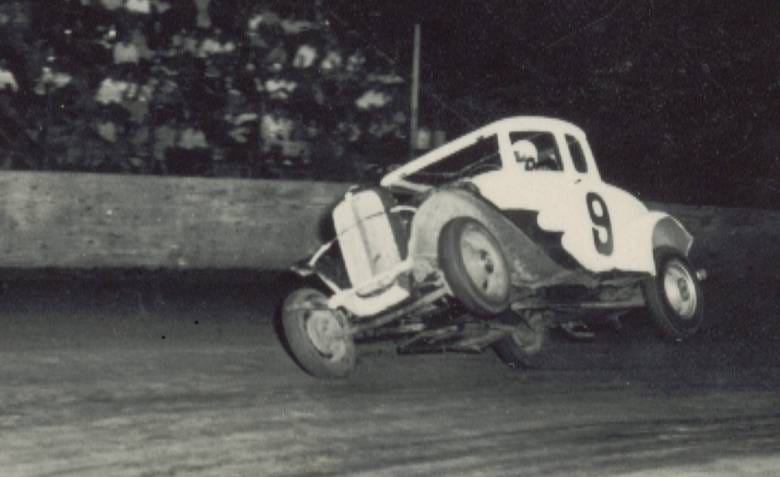

Dirt track modified racing in the 1960’s.

It happened this way. I was 16, my brother Frank was 14, and we were in Austin, Texas for a week visiting my Uncle James, who was flying B-52 bombers out of nearby Bergstrom Air Force Base. Uncle Jamie, as we called him, endeared himself to us early in life by being a car nut. He bought an Austin Healy 3000 when we lived in Germany and flipped it on a mountain road, but somehow survived and immediately bought a 356 Porsche Speedster.

He and his wingman – they were flying F-100 fighters back then -- used to drive the Porsche to visit us in Oberammergau from an airbase near Furstenfeldbruck, a small Bavarian town outside of Munich, from which they flew patrols along the Czechoslovakian border. We knew exactly when he was coming because we could hear the distinctive exhaust note of his air-cooled four-cylinder engine echoing from the mountainsides as they roared into the valley and screeched to a halt in the parking lot downstairs from our apartment.

That Speedster turned me into a car nut as well. Uncle Jamie still had it in ’63 when we visited him in Austin, and amazingly, he allowed me to drive it, which I did every chance I got. Saturday night came around, and Frank and I were itching to take the Speedster out for a drive and came up with the excuse that we just had to take the car to a race at a nearby dirt track. We didn’t know anything about automobile racing, but anything to get our butts into the bucket seats of that Porsche, don’t you know. We figured Uncle Jamie would approve our plan to take his precious car out at night if the destination was a racetrack, and we were correct.

We arrived at the track to discover a dilapidated set of wooden bleachers overlooking a sad little quarter-mile oval track. I think it cost us 25 cents each to get in. There was a hotdog stand in a lean-to shed behind the stands, so fortified with nickel hot dogs and nickel Cokes, we took our seats about half way up the bleachers and waited for the racing to begin.

The track was illuminated by a few forlorn spotlights mounted on pine telephone poles, and there was a chicken-wire fence about eight feet tall between the stands and the track allegedly protecting the spectators. Soon enough, they announced the first race over a tinny loudspeaker. They were called modified stock cars, but what they were was stripped down 1930 to 1940 Fords and Chevys. Their fenders and hoods had been removed, exposing the tires and engines. They were dented and wired-together and the numbers on the doors were hand painted, but they looked and boy did they sound like race cars.

A flagman standing in the infield dropped the green flag and off they went in a confusing mess of smoke and rubber and steel, bumping into each other as they jockeyed for position. The track had been watered to keep the dust under control, and the cars showered us with little bits of clay that flew from their tires as they skidded around the corners.

Finally a ’34 Ford emerged from the pack and took the lead. The driver must have been popular, because a cheer went up from the stands. He made a couple of laps and was crossing the start-finish line when suddenly there was a huge explosion and fire shot skyward from the car’s open engine. Frank and I looked on in wonder as a ball of flames arced into the sky higher and higher until it reached its apex and started coming down. It took us a moment to realize the ball of flames was descending straight towards us, and before we could do anything, a red hot piece of steel trailing a long tail of flames landed on the bleachers between us and bounced skyward, continuing its journey into the stands behind us where it finally came to rest, still glowing red hot and smoking.

Frank turned to me open-mouthed and said “cool!” Down on the track a safety crew was spraying the flaming race car with fire extinguishers. A man wearing huge leather gloves came running up the stands and picked up the red-hot glowing piece of steel and carried it past us, heading for the pits. It was a carburetor.

That was all it took. I was hooked. I went to every dirt track race I could find in the years to come, from Williams Grove Speedway in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, to a little track outside Colorado Springs where I was stationed in the Army. I found a track near New Orleans when I lived there in the ‘80s, and in 1992, when I moved to Los Angeles, I discovered Ventura Speedway on the fairgrounds at the beachside town about an hour out of Hollywood.

I went to practically every race they held there for the next 15 years, and to races at Perris Auto Speedway out near Riverside, and the dirt track in Bakersfield to the north in Kern County, and to a delicious little oval cut into a hillside right next to the 101 freeway near Santa Maria on the Central Coast.

What I enjoyed most in California was sprint car racing – small, open-wheeled cars that dated back to the earliest days of auto racing in this country in the 1920’s. They were primitive – essentially an engine, two axels and four wheels and a roll cage with barely enough room for a driver and a boat-tailed gas tank hanging off the rear end like an afterthought. They weighed about 1300 pounds wet (with gas) and ran alcohol-fueled V-8 racing engines with about 750 to 800 horsepower, one of the highest power-to-weight rations in all of auto racing. Sitting in the pits behind their trailers as crews worked on them before races, they looked cute. On the track, they were fearsome powerful beasts which on the 1/5th mile oval at Ventura spent nearly the entire time they were on the track going sideways with both rear tires smoking.

I went to so many races I got to know most of the people who sat around me in the stands and a good number of the drivers as well. I took my daughter Lilly to the races with me from the time she was three years old. Lilly and I took my son Lucian to his first sprint car race when he was one year old. I figured out a way to take two buckled nylon straps and fasten his stroller onto the bleachers, where he sat happily watching the races until he was three. By that time he had gotten to know the two sons of Chris Wakim, one of the best drivers at Ventura, a wonderful guy who had a day job as a machinist. Lucian and Chris’ boys would go down to the bottom rows of the stands and gather the bits of clay that flew off the race cars’ tires and carry them back up into the stands and mold them into a small banked clay oval and “race” their Hot Wheels sprint cars around their track.

It was good old fashioned family fun every Saturday night. Admission was $12 for adults, $10 for kids over the age of 12, with younger kids free. A hamburger at the concession behind the stands was three bucks, a Coke was a dollar, and popcorn was $1.50. Sitting in the stands at Ventura, you could see the foothills of the Santa Monica mountains straight ahead, and if you turned your head, you could see the sweep of the Ventura bay just past the track parking lot to the right. In July, when it was 90 in L.A., you had to bring a jacket or a sweater to the races in Ventura where the temperature went into the 50’s after the sun went down. It was heaven on earth.

Damien “The Demon” Gardner taking a corner at Perris Auto Speedway

Out at the Perris speedway, my favorite driver was a 17 year old kid named Damien Gardner from northern California whose father and mother amounted to the entirety of his pit crew. He raced against veterans who came to the track in tractor-trailers with two and sometimes three back-up cars. I remember the first night Damien ran at Perris. He qualified in the top five and won his heat race, so he made the “Dash,” a three-lap race for the top six finishers in the heat races that determined the starting places on the grid for the 30-lap feature race for the night. Damien started on the third row. Ahead of him were three of the best sprint car racers in the United States: Rip Williams, who had been driving for about 20 years and had won more than 50 features; Corey Kruseman, about 30, who had won almost as many features as Rip; and Richard “Gas Man” Griffin from Albuquerque, New Mexico, who had won more than both of them.

The starter dropped the green flag and somehow on the first lap 17 year old Damien Gardner shot through all five of the other cars. As he came around the fourth turn and drove his sprint car at over 130 miles per hour down the front straight, he waved his hand and pulled away from the veterans, finishing almost 10 car lengths ahead of the next racer.

When the speedway announcer interviewed him still sitting in his car right after the race, he asked Damien how it felt to have beaten three of the best sprint car drivers in the country. “Fuckin’ great, man!” shouted the excited 17 year old. The stands went wild, and a sprint car legend was born. From that moment on, his moniker was Damien “The Demon” Gardner.

Many race car drivers say if you can drive a sprint car and win, you can drive anything. In this country, at least, they are correct. I saw two of the winningest NASCAR drivers ever, Jeff Gordon and Tony Stewart, drive sprint cars at Ventura Speedway as teenagers. Other top NASCAR drivers got their start in sprint cars on dirt, as well – Kurt and Kyle Busch, Kyle Larsen, J.J. Yeley, Dale Blaney – the list goes on.

Dirt track racers learn to drive so-called “loose” cars, which is to say, cars that aren’t “hooked-up,” cars that lose traction in the corners. Because that’s the whole point of sprint car racing. The cars take the corners going sideways, with their back ends hanging out, wheels spinning, searching for traction, until the car completes the corner and heads down the straight for the next one, where the driver uses the brake to throw the car into another slide around the corner.

All race car drivers spend all of their time accurately aiming the car, integrating a zillion factors at once – their speed, tire adhesion, angle of the car, whether they should go low or high on the track, if they’re passing someone, whether there’s room between those two cars ahead of them…can they shoot that gap, or can’t they? Every moment of every race is a series of tiny, yet extraordinarily consequential decisions, because it takes only the smallest mistake for their car to “take ‘em for a ride,” in driver parlance. In other words, you are driving the car until the car is driving you, when you lose control and you are going for a ride.

Dirt tracks aren’t smooth. They’re rough, they’re rutted, they change from lap to lap, from race to race, so sprint car drivers learn to make an endless series of adjustments as a race goes on. Traction is good “at the top” of the track, near the fence…and then it’s not. “Down low” is good, near the inside of the track…and then it’s not. The best drivers feel the car through their butts, they can tell what the car is doing, how far they can push it, how it will adhere to the track if they turn sharply, how to ride a skid up in front of another car in what they call “a slide job” to pass, all because they can feel it through their butts.

Every once in a while you’ll see a driver shoot a gap between two cars that doesn’t look like it’s there. They can tell an opening will appear before it happens. Drivers like Damien Gardner not only feel their own cars, they feel the other cars. They can tell when the car ahead of them will lose traction and skid up the racetrack and open up a space they can drive through. They can predict a change in the surface of the track from one lap to the next. They’ll know when the “bottom opens up” before other drivers do. They can pass another car with just a tiny twist of the wheel to push their rear wheels past the front end of another car by inches because they feel it. That’s how they make it happen.

There used to be a paperback book you could buy that listed all the dirt tracks around the country. I remember back in the ‘90’s, there were about 1,500 of them. I saw an older edition of the book from the ‘70’s when there were 2,500 local dirt tracks, most of them on the edges of small towns in what used to be corn or wheat fields or old industrial sites. Gradually, many towns expanded and housing developments moved in and people started to complain about the noise of the largely unmuffled race cars and tracks were forced to close by zoning boards that listened to voters rather than racers.

That almost happened in Ventura back in the late ‘90’s. Some wealthy subdivisions sprang up on the side of the hills above Ventura and McMansion owners started to complain to the town council and there was talk of closing the track on the fairgrounds. A bunch of fans and drivers formed a committee to save the racetrack. One of the drivers and I went to the local historical association and found an old photograph of Ventura that showed the town in the foreground, with wooden sidewalks and horses tied up to rails outside stores, and in the background, down there near the ocean, in the middle of farmland owned by a local family was a half-mile dirt oval used for horse racing. The date on the photo was 1890. The horse track turned into a race track for cars sometime in the ‘20’s. There had been racing of one kind or another at what later became the Ventura County fairgrounds for over a hundred years.

We won the fight to save Ventura Raceway with petitions and history and votes. There is racing almost every Saturday night, now with mufflers in deference to the McMansion owners across the way. And these days you can see sprint car racing from the Midwest on MAVTV Motorsports Network on cable, satellite and ROKU and streaming services on tablets and cell phones. There’s a subscription service that shows dozens of dirt and pavement track races all around the country every week called Floracing. For a monthly fee of $12.50, about what I used to pay for the Saturday night races, I can watch Damien Gardner and Rip Williams’ two sons race their sprint carts on the same tracks I took my kids to back when a teenage Lilly was indulging her father and Lucian was pushing Hot Wheels around his little clay track with the other boys. And I can do it all sitting on my couch right here on the East End of Long Island.

Is this a great country, or what?

Thanks for today's great escape❣

Cottage Grove, Oregon has a dirt track like you describe.