Ed Fancher, the publisher of the Village Voice, died at 100 years of age last September. This column is an expanded version of my remarks delivered by Zoom on Saturday for his memorial, held at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park, near where Ed lived.

Ed Fancher was one of the three men who founded the Village Voice in 1955. The others were Daniel Wolf and Norman Mailer. All three were Infantry veterans of World War II. They returned from the war to a country that, having won the war, had settled into the stultifying years of the 1950’s. None had any experience in journalism, but dissatisfied by the daily newspapers that dominated the New York City landscape, they decided to found a weekly that would break out of the mold of conventional newspapers. They ended up changing journalism itself.

I met Ed when I was invited to the Village Voice Christmas party in December of 1967. I had been writing letters to the editor of the Voice from West Point for the previous year, and Wolf and Fancher decided to invite this unusual cadet to their party. Little did I know, but my name was familiar to them, as Ed Fancher had served under my grandfather when he commanded the 5th Army in Italy.

The party happened on the weekend of the Navy game, so I was attired in my Dress Gray uniform when I knocked on the door of an apartment on West 10th Street in Greenwich Village. I asked to meet the founders of the Voice, and after making my way through the crowded space that included guests such as Mayor John Lindsay, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and Ayeh Neier, the president of the ACLU, I found Wolf and Fancher and Mailer in a back room standing together with their backs to a bookcase. I introduced myself. Wolf shook my hand and informed me that he was an infantry veteran of the war in the Pacific. Mailer said the same thing. When I shook Ed’s hand, he told me he had served in the 10th Mountain Division under General Truscott in Italy.

Astounded, I told Ed that I had thought that a party given by the Village Voice in Greenwich Village was about as far away as I could be from my heritage, and yet, “here you are, another guy who fought under my grandfather. I give up.”

That got a laugh. Little did I know that the next three years would see me graduate from West Point, leave the Army, and end up working for Wolf and Fancher at the Village Voice.

At the Voice, Ed didn’t make a big deal out of his service in the army in World War II, but his time serving in the United States Army was extraordinary, and I want to celebrate it here.

He enlisted and joined the 10th Mountain Division and went for ski and mountaineering training in Leadville, Colorado. He fought to save not only our democracy but all of Europe from Adolph Hitler. More than 300,000 survivors of the Holocaust were liberated from the camps at least in part because of what Ed did one night in February of 1945. He was enormously proud of his service in the 10th Mountain, and he had a right to be.

My grandfather, Lieutenant General Lucian K. Truscott Jr., commander of the U.S. Fifth Army in Italy, ordered General George Hays to deploy the 10th Mountain Division in the valley and hilltop villages below Mount Belvedere and to begin planning an attack—to be known as Operation Encore—for late February 1945. This attack became known as the Battle of Riva Ridge, named after 4,642-foot Monte Riva, that overlooked the entirety of the Belvedere massif. Because Mount Riva was fronted by a nearly sheer cliff more than 2,000 feet high, the Germans thought it the least likely of the Belvedere mountainous region to be attacked. The thousand-man 1st Battalion of the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment, with the addition of F Company from the 2nd Battalion, was given the mission.

The Nazis did not count on the mountain training of the 10th Mountain Division. To take Riva Ridge, the 10th Mountain dispatched rock climbers from the 86th Regiment to reconnoiter the east side of the ridge. Ed was one of those rock climbers.

One time when I visited Ed and his wife Vivian at their apartment on Gramercy Park, he took me into his study and proudly showed me a photograph of him and two Italian partisans who had fought in the Italian resistance. That was Ed’s team of scouts. It took over a week for the scouts of the 10th to plot five routes of attack. Ed told me he and his Italian partisans made three climbs up Riva Ridge at night, looking for the best route to the top. Eventually, they mapped out one of the four trails that were picked for the attack.

As night fell on Sunday, February 18, the men from units of the 86th set out to climb the five snow-covered trails to the summit of Riva Ridge. The the Nazi positions at the top of the ridge had not been shelled in advance by the 10th Mountain’s artillery, because the attack had to be a complete surprise, or the attacking soldiers would have been fired upon by the Germans occupying positions at the top of the ridge.

Ed was at the point of one of the advanced climbing parties that led the rest of the battalion up the mountain. They wore soft caps so that helmets could not fall off and make noise clattering down the rocks. Four lanes of attack were chosen from the five that had been mapped out. In the dark of night, the soldiers had to climb in single file, so they could follow the scouts who knew the way. This made them even more vulnerable to attack by the Germans if they were found out.

The climb took all night. Ed said that at dawn, the raiders reached the crest of the cliff and caught the Nazi soldiers sleeping in their foxholes. Hearing firing from the 10th Mountain attack, German soldiers held in reserve on the far side of the ridge came out of their foxholes still in their underwear and were killed or taken prisoner immediately. Once soldiers from the 10th Mountain had secured the top of Riva Ridge, the battle for the Mount Belvedere area continued with continual German counterattacks. The Division ended up suffering more than 900 casualties, with 192 killed in action and 700 wounded. But the battle that had been expected to take two weeks was won in five days. Ed and his scouts were unsung heroes of that battle. It was because of their reconnaissance that the first Battalion suffered only one casualty in the initial nighttime attack on Riva Ridge.

The victory at Riva Ridge helped the 10th Mountain Division open the pass that led to the Po Valley. The division was the first to cross the Po River on the 23rd of April. Two days later, they had taken Verona. They fought their way through the hills and mountains to Lake Garda and launched an amphibious attack on Mussolini’s headquarters in a villa on an island in the middle of the lake. The German Army surrendered on May 2, 1945, which became known as V-I day, for Victory in Italy. The war in Europe ended six days later on May 8 with the surrender of the Nazi army in Berlin. The men of the 10th Mountain celebrated victory by holding a ski race in the still-snow covered Italian alps

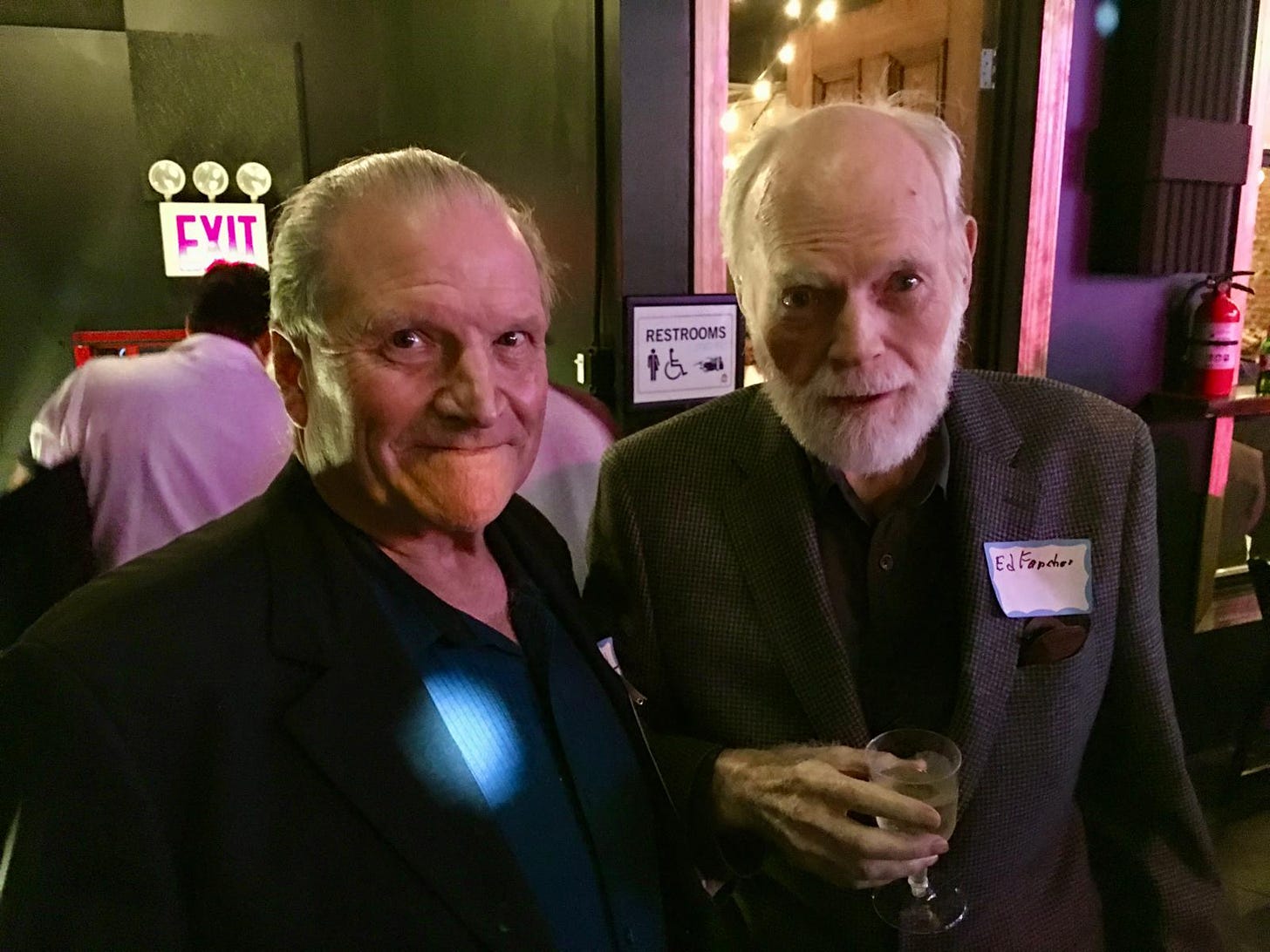

Ed and I remained friends for the next 56 years. We always thought that there was a certain symmetry to the fact that the grandson of a general ended up working for one of the soldiers who fought under his command years later in New York City.

I loved Ed. We all did at the Voice. I felt privileged to know this man who had three distinguished careers: one as a soldier, one as a psychologist, and the other as the publisher of the Village Voice. I miss him, and I salute him.

This is a beautiful story…. Thanks for sharing such an outstanding memory with us.

Damn, can you write, Lucien. I was headed in to help get dinner ready when your post popped up and I thought I'd give it a quick scan and read it later. HA! Three words in, and I'm still in my office, late again. We all need more of you, just writing. As I've said before, the shit won't smell any worse if we ignore it for a day or two, once in while. Thank you for sharing another great one with us.