It’s 2021, man. How about subscribing?

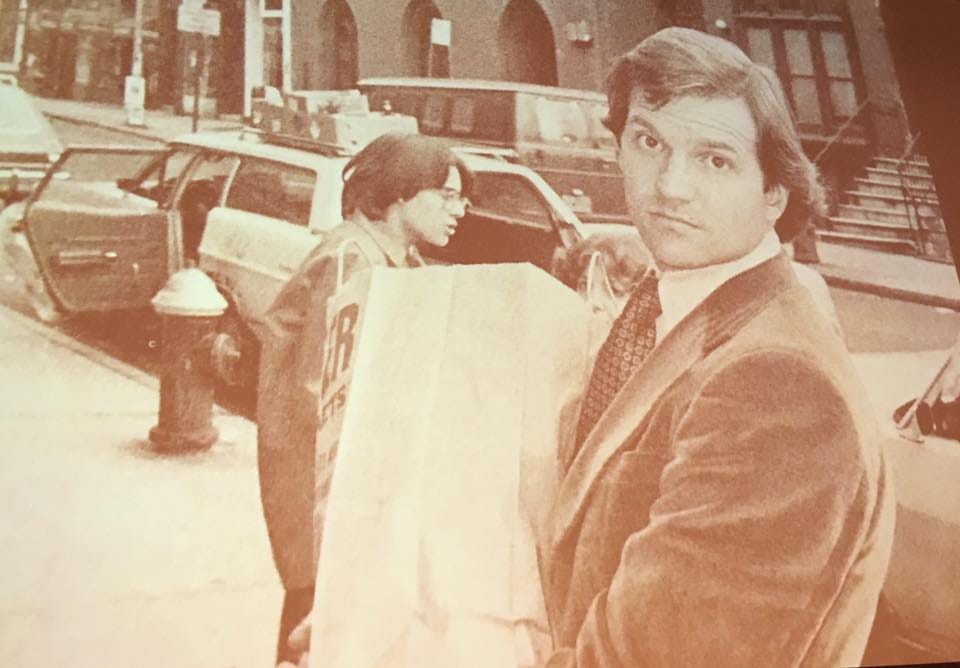

The author in the 70’s.

The subway ride on the IRT Lexington line uptown to the Madison Avenue offices of Esquire Magazine was one of the most exciting you could take back in the day. Along its length were the exits you took for the offices of most of the slick magazines of the era – New York, Harper’s, The Saturday Review, The New Yorker, Penthouse, Time, Newsweek, GQ, Life, and of course, the Cadillac of the men’s magazines, Esquire itself. Every once in a while, a friend toiling away as a “researcher” or as some sort of junior assistant editor would invite you up to the office for a Friday afternoon blow-out celebrating the 20 years some alked-out senior editor had put in, so you’d take a ride uptown and get to hang out in an office with views of Central Park and drink the free booze and gobble down the mini-roast beef sandwiches and listen to grizzled veterans of the magazine wars tell stories about the time they got drunk with Kirk Douglas on the set of a movie in Mexico.

And then there came the day you were downtown in your cubicle at the Village Voice on University Place, and the phone rang and you were summoned to the offices overseen by the legendary Harold Hayes, the Esquire editor who set the standard for men’s magazines in mid-century America. You were going to walk the boards trod by Norman Mailer, Nora Ephron, Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe, John Sack, and too many others to count. You were going to peer into the same offices, drink from the same water fountain, walk the same hallway lined with the magazine’s classic covers, most of them designed by the famous art director, George Lois.

And oh, let’s not forget that you’d get to check out the same editorial assistants in their uptown short skirts and high heels and shiny lipstick and manicured nails, so unlike the downtown girls you were used to in their black stockings and black boots and long, straight hair. Which you proceeded to do, the minute the assistant to Tom Hedley, who served as Esquire’s youth and trends editor, came out to reception to take you back through the warren of offices to her desk, where you took a chair and waited to see Tom, who she informed you was “finishing up a call.”

It was the first of many times over the years you would hear those words. It would seem that uptown magazine editors and Hollywood production executives and big-time literary and film agents were always “finishing up a call.” And so you were left in the company of their assistants, who were in nearly every case on both coasts female and young and astoundingly good looking.

There is a nearly overwhelming desire to begin the next sentence with the words, “as a young man,” for that is indeed what you were, but that’s not why. Looking for a reason to excuse the behavior of this “young man” is more to the point, as if the exigencies of youth were there for you to get away with exploiting every opportunity that came knocking in heels and lipstick.

The way the world organized itself back then was already overwhelmingly to your advantage, and then lo and behold, along came the 60’s with its dreams that everything would be cool, man, all you had to do was sit back and let the grooviness wash over you in clouds of pot smoke and languorous (female) fingers of free love. They put this new world order on the covers of Time and Newsweek and ascribed it to “hippies,” but everybody knew that was bullshit. Hippies didn’t have to think up another way to exploit the trick-bag of maleness.

Putting sex on the top shelf at the American supermarket was hard to miss. They featured “the pill” on the cover of the news magazines, for crying out loud! It was like advertising a sale at the morality store. It wasn’t lost on preternaturally eager young male minds that not only was “the pill” girls’ responsibility, they were the ones who paid for them. If you had grown up in the repressive 1950’s and early 1960’s when sex was treated like something you had to wait for like good weather, the idea that anything having to do with the female body being “free” was manna from heaven.

When you arrived in the chair next to the desk of the gorgeous young assistant to the “youth” editor at Esquire, you were wearing a fringed suede jacket you had bought in a western store back in Colorado, and a pair of Levis and rough-out cowboy boots and a wide-brimmed African safari hat you had picked up in a store called Hunting World somewhere on the east side, and you probably would have looked absolutely ridiculous, except it was 1970 and you were 23 and walking around dressed like you were some kind of cowboy outlaw made perfect sense.

It apparently made sense to the comely young editorial assistant at Esquire, too, because lo and behold, after your meeting with Mr. Hedley, it was just about quitting time, and she was straightening up her desk and getting her purse and preparing to leave for the day when she announced that she and a bunch of her friends were meeting for a drink after work, and did you want to join them?

She was from Ohio, had gone to Smith -- or was it Vassar -- she was working her way up the editorial food chain at Esquire, her friends were in advertising, or banking, or publishing, and they were all way over-educated for their jobs, and everyone was in their 20’s in New York City, and the guys were in suits and ties and the girls were in their short skirts and tasteful blouses, and you joined her friends at some midtown boite and you stuck out in your fringed suede jacket and cowboy boots because you were supposed to stick out. It occurred to you about half way through the slew of beers the group was quaffing that she was showing you off, and why not? You had a piece on the front page of the Voice that week, you’d written for the Saturday Review, you just nailed down an assignment at Esquire, and the world, as they say, was your oyster.

After the drinks with her friends, you walked her to the nearest Lexington IRT stop and what do you know, but she invited you up to her studio apartment on the East Side and before you knew it, you were snuggled beneath the obligatory racoon fur throw she had picked up on St. Marks Place that was exactly like the racoon fur throw you had on your bed in your $40 a month sixth floor walk-up on Avenue B.

So that’s what the free love deal was about! Suddenly the whole male-female thing wasn’t hidden away down a rabbit warren of rules and moral decisions and judgements and weirdness, it was right there out in the open. Sex wasn’t something you negotiated your way through like a maze. You just went for it, both of you.

But lying there in the dark afterward with her asleep on your shoulder, you knew that free love wasn’t a “deal,” and it wasn’t fair. Sure, it took two to tango and you were the same age and at about the same station in life, and both of you had moved to the city within the last year. Both of you were in your first apartments. Both of you were still feeling your way in your jobs, unsure of where the shoals and rocks were, sailing through a fog of uncertainty and newness.

Going to bed “on the first date” was what it was about, it had been a mutual decision, but you knew you held the upper hand. You couldn’t spell it out for yourself, but you knew. Even though you were in her apartment, in her bed, at her invitation, it wasn’t a level playing field, not even close, and both of you knew it about as deep down as either of you were capable of going at that moment. Even nakedness was unequal. You just stripped off your jeans and shirt and underwear and hopped under the covers, but for her there was a thing she went through, a trip to the bathroom was involved, with an appearance at the bedside in some kind of nightdress, and when she slid into bed next to you, her nudity wasn’t just there, like yours. It was revealed. That it was a bigger deal was unspoken, but it was there. Yours was a reaction. Hers, somehow, was still a decision, even though it was supposedly “free” and unattached to the old rules, which hung around the sides of the bed like a silent chorus ready to sing out judgement and cost.

Breakfast in the morning was at a nearby Greek diner, and you were both chatty and relatively free of awkwardness, even though you barely knew each other, and that felt right, like it was supposed to be like that. You rode the subway downtown together, she got off after a few stops to walk over to the Esquire office, and you continued downtown to Union Square, the stop for the Voice. You called her later that day. You couldn’t meet up after work – the Voice city editor had you covering a local planning board meeting on a Rockefeller plan to demolish the West Side highway to make room for high rise apartments along the riverfront – but you made a date for the next day.

You picked her up at Esquire and headed uptown to her place. This time, passing a market on the way, you suggested picking up something for dinner. You’d make steak and baked potatoes. It would be fun to stay in, maybe watch an old movie on TV.

Dinner was an exercise in how unprepared her bachelorette kitchen was for actual cooking and eating a real dinner – you found a frying pan but there was nothing to flip the steaks with -- but it worked out, the two of you eating off plates on your laps watching a black-and-white noir on her TV with rabbit ears and a snowy picture. This time there seemed to be a mutual decision to get ready for bed, both of you making trips to the bathroom, brushing of teeth, all the rest of it. The phrase like grownups came to mind as you waited for her under the racoon fur comforter.

You could tell there was something off the minute she got into bed. You kissed her, and then she hid her face in your shoulder and you could feel her tears. She was crying. Not sobbing, just crying gently, almost to herself. She pulled away and started to apologize. She wanted you to know it wasn’t about you, it wasn’t about having sex, or not having sex, or about having had sex before, which would have made a certain kind of sense given the complete absence of rules both of you seemed to recognize without talking about it out loud. No, she cried because she was lonely, and she was homesick, and she wondered if she had made a mistake moving to New York like her friends and getting a job at a big magazine and doing all the exciting stuff she was supposed to be doing because her friends were doing it, going to clubs, and staying up late, and smoking pot and drinking more than a little too much almost every night, and then ending up back in her studio apartment on East Ninety-something street by herself eating take-out from the corner deli and crying herself to sleep almost every night even though if you asked her she would tell you honestly that she loved her job and most of the time living in New York was lots of fun, everything it was supposed to be.

So you stayed up that night talking and you even admitted that you had your moments down on Avenue B, when the only people to talk to were across the street at Stanley’s Bar on the corner, and they were all at least 10 years older than you, and to tell the truth, it wasn’t that much fun hanging out there and talking into the night.

But even your confessions to one another were unequal. She seemed to be coming from someplace vulnerable, and you were just complaining. It wasn’t the same, and because of that you couldn’t wait to get out of there. You even toyed with the idea of coming up with some reason to leave, but you couldn’t think of one that was even marginally believable, so you stuck it out, and the next morning neither of you wanted breakfast and she got off the subway at the same stop for Esquire and you continued downtown to the Voice.

This time you didn’t call her right away, you waited. A day became a week. You thought maybe she would call you, but she didn’t. You were working on the story for Esquire, and there wasn’t any reason to stop by the office until you were finished and it was time to turn in the piece to Hedley, so you waited some more.

By the time you turned in the piece, she was gone, and there was a new girl in her place, just as pretty, just as young, just as sexy in her little black skirt and heels. This time nothing happened between you, and it was just as well. You were already hanging out with one of the waitresses from the Lion’s Head, the writers’ bar on Sheridan Square where people from the Voice and the Times and the Post and the News hung out, along with a few novelists and short story writers who had the covers of their books framed and displayed on the wall across from the bar.

You were moving on, because you could. That’s what it was like to be young and be a guy back then. There weren’t any rules tying you down and obligating you to do anything but keep moving. You were learning there was a new game between men and women. Free love wasn’t free, and at least some of the time, it wasn’t love, but that didn’t matter because everybody knew all you had to do was wait and the rules would change, just like the weather.

Yup, it was the 70's. There were lots of 20 something women with the same thought pattern as you. We were not all insecure. We were experimenting and having a great time, just like you and holding the responsibility for our bodies. Never a better time to be alive.

Another great one Lucian, evocative of an era that seemed so full of unlimited prospects for all that is good and important, socially, politically, personally. When and where did the train leave the tracks?