Growing up Truscott

White, privileged, 6th great grandson of a president and that isn't the half of it

Some of my earliest memories are of visiting my grandparents at the farm they owned in Loudon County, Virginia. It was a wonderland for boys like me and my brother Frank, who was two years younger. There was a barn, of course, along with its attendant barn cats and their kittens and the occasional chicken who wandered in from the coop seeking a place to lay her eggs where she could sit on them without being disturbed by pesky humans who were in the habit of collecting them every day.

I remember one day Frank and I could hear a chicken clucking from somewhere within a huge pile of haybales. It was one of our jobs to seek out such a chicken and her illegal nest and carry her and her eggs back to the chicken house. Frank found a split between the hay bales just about wide enough for a chicken or, as it turned out, a boy, and we squiggled through and found her back there sitting on a nest of about six eggs. There were tons of bales of hay above us, but neither boys or chickens thought about stuff like the possibility of the stack shifting and entombing us. We grabbed her and her eggs and scooted back through the narrow opening in the pile of bales and delivered her and the eggs back to the coop, and then of course, we kept exploring: There was a workshop shed with a gigantic stone wheel for sharpening axes you powered by treading on two wooden slats connected to the turning mechanism by big leather straps. The shed smelled of motor oil and sweat and rusty iron, and when I visited the same farm about 20 years ago looking for Ruth Basil, their housekeeper, the workshop looked and smelled exactly the same as it did in 1951, complete with the big stone sharpening wheel.

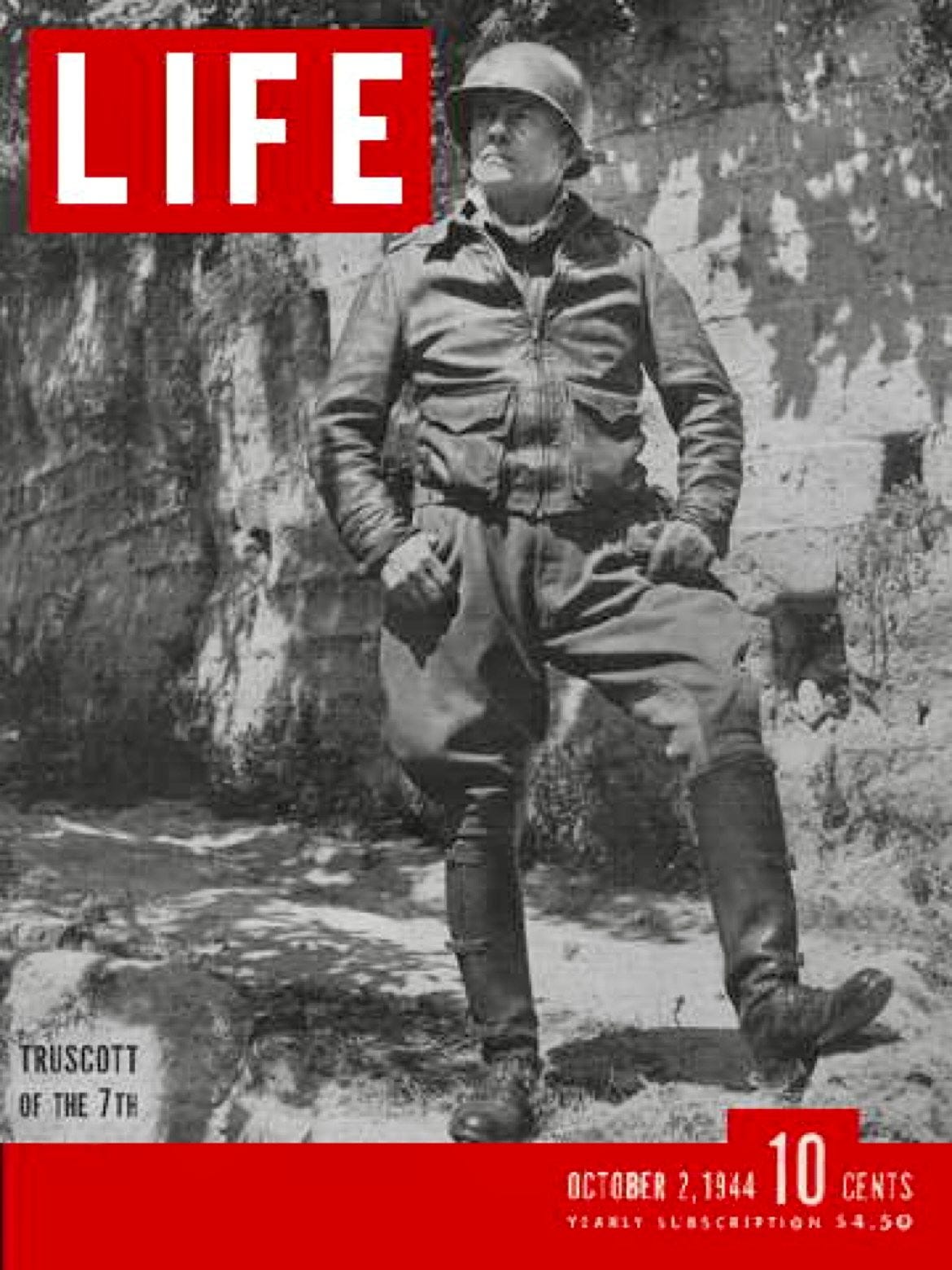

The reason we were there of course was to visit grandma, Sara Randolph Truscott, and grandpa, General Lucian K. Truscott Jr., who was only a few years removed from his command of the 3rd Infantry Division, the 6th Corps, the 7th Army and the 5th Army during World War II. Everyone but Frank and me and Grandma called him “The General,” and would until the end of his life in 1965. Grandma called him “Looooshin,” his name strung out like that in her distinctive Virginia drawl, and it was a family joke that when she would go out on the back porch of the farmhouse, which was constructed of local stone and roughhewn wood, and called out his name, three of us named Lucian would come running.

I knew he was a big general in the war, but it would be years before I realized just how well regarded and famous he was and what that meant. Great men came to visit him out there in Loudon County, among them General Walter “Beetle” Smith, who had been General Eisenhower’s chief of staff during the war and by 1950 had been appointed Director of the CIA. He is a character in the movie “Patton,” as is grandpa, and if you want to know the fame that attached to the greatness of those men in that war, there it is, larger than life on the silver screen – or these days on cable television. I still hear from people who have watched “Patton” with questions about the scene between grandpa and old “Blood and Guts” in a bunker during the battle for Sicily. It’s totally accurate because it was taken almost verbatim from grandpa’s war memoir, “Command Missions,” which did not mince words in its depictions of others in the war, including men like Patton and Mark Clark.

I heard officers who were friends of my father during the 50’s and 60’s when they visited our house talking admiringly with dad about his father the general. During the summers when Frank and I visited grandma and grandpa where they settled later just outside Washington D.C. when he was a deputy director of the CIA, I would find myself serving martinis to and at dinner seated next to men like Allen Dulles, director of the CIA, and Richard Helms, a future director who at that time was described to me as grandpa’s aide. They would visit late on Friday afternoons and sit out on the screen porch, and it was my job, attired in khaki pants and a starched white shirt, to sit just inside the door from the porch on a dining room chair and wait for grandpa to bellow, “Boy! Bring us another pitcher of martinis out here!” I would scurry out to the porch and collect the empty pitcher and mix a new batch in the kitchen and deliver it to the porch and take my seat inside the door, awaiting the next bellowing command from the general.

When I started dating, I was questioned about grandpa by girls’ fathers, who were majors and colonels on Army posts: what kind of a man was he to be around, was he as tough as his reputation. As the years went by, I ran into man after man after man who had served under him in the war and recognizing my name, would engage me in conversation about him, or tell stories they had heard about him. For years, it was simply a consequence of being General Truscott’s grandson and nothing more.

That changed one day at LaGuardia airport when I deplaned from a flight somewhere and discovered I had only a dollar in my wallet, not enough money for the bus from the airport to the city, much less the bus from Port Authority back to West Point. In those days before cash machines, some airports had counters for banks like Manufacturers Hanover Trust where you could cash a check if you had an account there. I approached such a counter with a check written to cash – a great big $10 – from my bank near West Point and asked the teller if I could cash it. He sort of chuckled and asked if it was a Manny-Hanny check, and I answered no. He said, well I can’t cash it for you. Sorry. Desperate, I shoved the check across the counter. He looked down and saw my name printed on the check and looked up at me, startled. “Are you related to General Truscott?” he asked, open-mouthed. “He’s my grandfather,” I answered. The teller took the check and held it aloft like it was a treasure of some sort. “Well, young man, it will be my privilege to cash your check. Let me tell you about the months and years I served under him in North Africa and Sicily and Italy,” and off he went with his stories about the fabled “Truscott Trot,” which was grandpa’s tactic with the 3rd Infantry Division when he ordered them to run for 50 minutes and rest for 10 all the way across the island of Sicily as a way to surprise German units who were unaware that an entire division of soldiers could move so fast on foot.

My name did not grant me any advantages at West Point however, despite the fact that grandpa’s portrait hung in Grant Hall alongside those of Pershing and Eisenhower and Patton. West Point strove to be egalitarian with its Corps of Cadets, among whom were more cadets who were descended from other famous generals. But there would be other times and places when my name was recognized and being General Truscott’s grandson was advantageous. It happened again when I was invited to the Village Voice Christmas party in December of 1967.

I had been writing rather contentious letters to the editor of the Voice for over a year by then, and I can’t tell you how surprised I was when one day in the mail arrived the invitation to the party on a Friday evening on West 10th Street in the Village at the home of the Voice’s publisher, Edwin Fancher. It so happened that I had that Friday off because of the Navy game the next day in Philadelphia, so I made my way down to the Village in my Dress Gray uniform and long gray overcoat, which I hung on a rack in the hallway of the townhouse where the party was. I knocked on the door a couple of times, but nobody answered. I could hear the party in there, and I knew I was at the right place, so I just opened the door and walked in. The door hit Mayor Lindsay’s arm, causing him to toss his drink right into the chest of Bob Dylan.

That was my entrance to the Village Voice Christmas party. Because I was in uniform, I was easily recognizable, and people who worked at or wrote for the Voice immediately engaged me in conversations about a particular letter I had written or with questions about how a West Point cadet had ended up writing letters to the Village Voice. I was looking for Dan Wolf, the editor of the Voice, and Ed Fancher, and Norman Mailer, who founded the paper with the others in 1955 and was still a part owner. It took me more than an hour to work my way through the crowd to a back room in the townhouse where I was directed to three rather distinguished looking men standing across the room near a bookcase.

I recognized Mailer from his photographs, of course, but I walked up to one of the other men and stuck out my hand and introduced myself and thanked him for inviting me to the Voice Christmas party. “I’m Dan Wolf,” he said. “We’re happy to have you. By the way, I served as an infantryman in the Pacific.” He turned to the next man and said to me, “Lucian, this is Ed Fancher, our publisher.” I shook his hand and as I did so, he looked at me smiling widely and said, “It’s great to finally meet you, Lucian. I served under your grandfather in Northern Italy in the 10th Mountain Division when he commanded the 5th Army.” Then he turned to introduce me to Mailer, who had also served in the infantry during the war in the Pacific and had written the famous war novel, “The Naked and the Dead.”

I shook Mailer’s hand and said I was glad to meet him, and then I turned to Fancher and Wolf and said, “I’ve been trying to get out from under the shadow of my grandfather for years, and here I am in Greenwich Village at the Village Voice Christmas party with Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs and Joan Baez, and I find three more infantrymen, and one of them served under my grandfather. I give up.”

They laughed and so did I, and the irony wasn’t lost on any of us. But an uncomfortable fact was right there in front of me: Even at the Village Voice my name and heritage had been recognized and had probably influenced the decision to publish my letters to the editor. The same thing would prove true when I was invited to the offices of the New York Times by its famous Pulitzer Prize winning correspondent Harrison Salisbury, who had recently been appointed to be the first editor of the new “Op-Ed” page of the Times. It turned out that Salisbury had met grandpa when he was with the United Press during the war. Salisbury had also known him when he was Moscow Bureau Chief for the Times in the early 1950’s during the time grandpa was running the CIA in Europe from 1951 to 1955. He asked me if I wanted to write for the op-ed page, which I did, and for which I have written ever since.

One of those times was the day I called the editor of the op-ed page and asked if they wanted a story on the controversy surrounding the release of the DNA evidence which seemed to prove that Thomas Jefferson had fathered the children of his slave Sally Hemings. I told him I was a sixth great grandson of Jefferson and would be attending the annual meeting of the Monticello Association, which was and is comprised of the white descendants of Jefferson. Clearly the DNA evidence would come up at the meeting, and it did, and I wrote about it in the Times. At no point did anyone at the Times ask me how I was descended from Jefferson or ask me for any sort of proof. I had been known to the Times at that point for almost two decades, but never as a Jefferson descendant. In fact, this would be the first time I wrote about it. But I was Lucian Truscott. It was just assumed that I was telling the truth. I came from a great American family not even taking into account the Jefferson connection. It was yet another time when having the name Truscott moved me to the front of an imaginary line.

And then there was the time when being a Truscott delivered instead of privilege an unexpected delight. It happened in 1985 when I was living in the French Quarter in New Orleans. I got an invitation out of the blue to a kind of “spring fling” party in the most famous garden in the Quarter. It was a walled garden belonging to a grand house on Ursulines Street I had heard about but never seen. When I entered, the party was in full swing. I looked around for who had invited me and was led to a book-lined study in the house where I was greeted by two men who were in the middle of watching a baseball game on TV. They introduced themselves and then one of them took the other’s hand and said, “We owe our lives together to serving under your grandfather. You see, we met in a foxhole in Italy when we were serving in the 10th Mountain Division in the winter of 1944, and we’ve been together ever since.”

Grandpa had taken the first step to integrate Black soldiers into the Army as commander of the 5th Army in Italy when he formed two all-Black regiments in the 92nd Infantry Division and prepared them for combat. Black soldiers were serving in segregated units and were given noncombatant tasks during the war such as driving trucks that ferried supplies to the front and acting as cooks and dishwashers and other menial jobs. In fact, grandpa had to create a mini-basic training camp behind the lines in Italy to train the Black soldiers for combat, as most of them hadn’t been issued rifles or trained to shoot them. The 92nd Infantry Division had a good record in Italy, and at least in part it was their performance in combat that led President Truman to issue an executive order integrating all branches of the military in 1948. Generals Eisenhower and Bradley, who were retired, testified against integration of the military at a hearing by the Senate Armed Services Committee. Grandpa was among only a few general officers to support Truman’s act to integrate the military years before the Supreme Court would order a greater integration of the country with Brown v Board of Education in 1954.

It was my great honor to travel to Capitol Hill in 1993 and lobby both the House and the Senate in favor of integrating the military for gay soldiers, sailors, Marines, and Airmen. President Clinton was forced to drop his plans to issue a Truman-style executive order to integrate gays in the military. Congress responded to pressure by conservative lawmakers and the Joint Chiefs of Staff by including language in the Defense Authorization Act enshrining a ban on gays serving in the military that had been passed in 1982. President Clinton issued a “compromise” Defense Directive in December of 1993 that became the dreadful “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy of not asking recruits whether they were gay but allowing expulsion if soldiers “told” and came out.

Looking on those dark days from now, when gay people serve openly in all the services and the Supreme Court has made same-sex marriage the law of the land, is a little strange. But it’s no less strange than looking back on a military that banned Black soldiers from combat units and segregated the races.

I like to think it’s no accident that Truscotts had a hand in overturning both of those disgusting racist discriminatory practices. I’m proud to have been born into my family for many reasons, but the greatest privilege of my birthright of all has been having a voice that carries as strongly as it does and is listened to at least in part because of its attachment to my family name.

To help support this newsletter and read more stories like this one, subscribe for only $60 a year or $5 a month.

I read your stuff because you are interesting, because you're a good writer and a good storyteller and because you have your own very interesting voice and ideas I would read your stuff if you, like me, were a 6th great grandson of nobody in particular. Not that my 6th great grandparents thought of themselves that way.

My father worked with him at the CIA and greatly admired him. I sat with those men at dinners, too. I remember hearing them talk about The General. You probably served a martini or two to Dad at the farm. It is always an honor to know a true hero. Thank you for this post.