How Rupert Murdoch began his career in ruining America

A tale of envy, avarice and incipient fascism in three parts

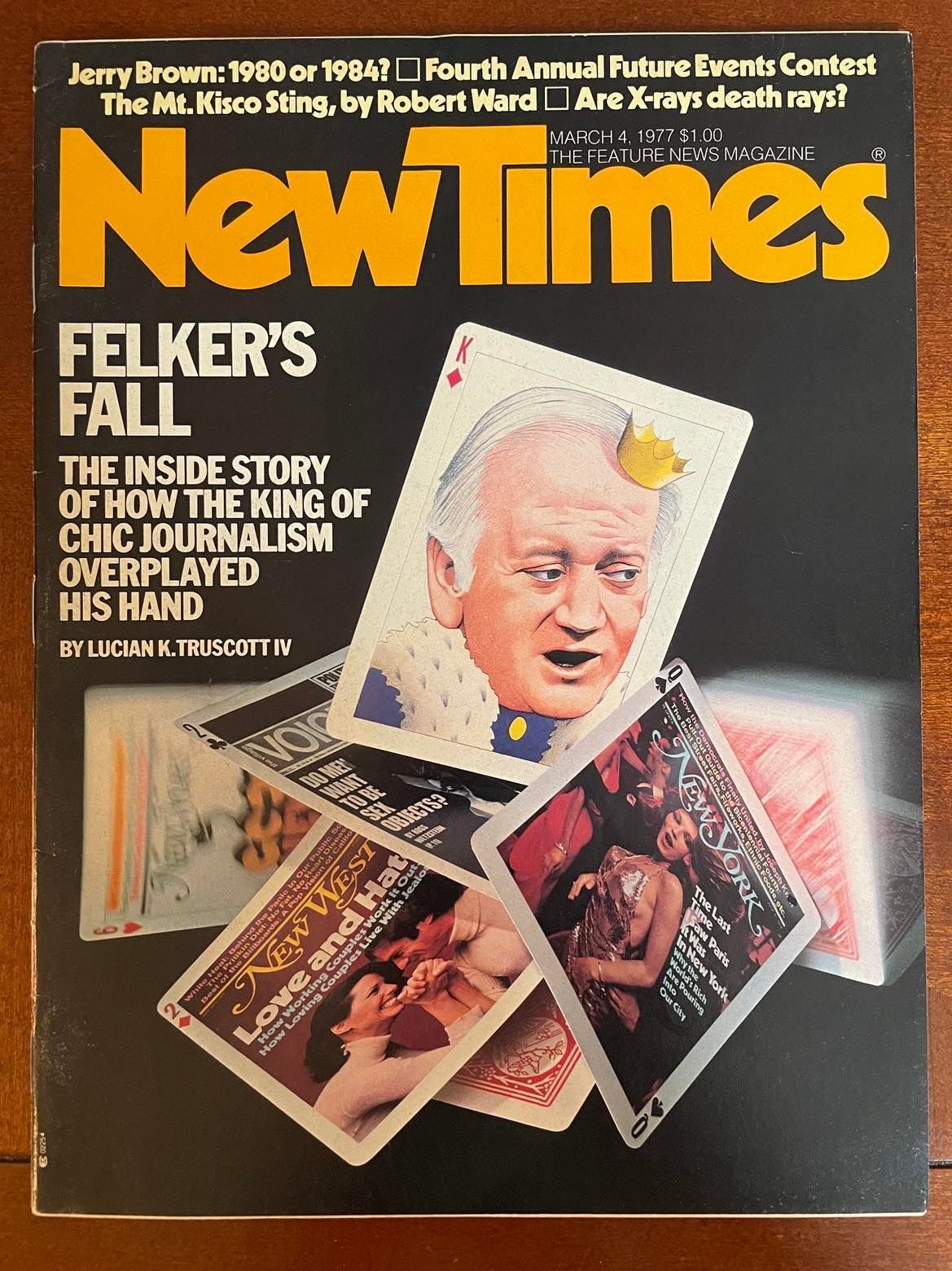

This is a story I wrote for New Times Magazine in March of 1977 about how Rupert Murdoch made his first move in American journalism by taking over the New York Magazine empire that then included The Village Voice from its chief executive, Clay Felker.

I had worked for the Voice as a freelance and a staff writer from 1968 until 1975, when I resigned from the paper specifically because Clay Felker’s editorship of the Voice had changed it from an eccentric and unpredictable downtown weekly into a newsprint version of People Magazine. Felker had bought controlling interest in the Voice in 1974 and set about immediately ruining it in the eyes of many of its readers and most of its staff. He fired the editor in chief and the publisher and several other editors on the staff, and there were immediate resignations from some writers.

Felker’s first cover story was a celebrity profile of, I think, the actress Jill St. John the week she had a movie coming out. The Voice had never before done a celebrity profile, much less run it as the entire front page of the newspaper. Felker had a reputation for yelling at his employees, and after a week or two of relative quiet at the Voice offices, he lived up to his reputation. One day I asked him if we could have coffee. At a nearby coffee shop, Felker asked me what was on my mind. I told him that he could yell and scream at everyone who worked at the Voice, but he wasn’t going to raise his voice at me. He looked stunned. I walked out just as our coffee was being delivered to the table.

Two days later, Felker gave me an assignment to the Middle East to cover a war that was supposedly brewing between Israel and Lebanon over the resigning of the Golan Heights peace accords. The war never broke out, so I ended up reporting on terrorism from Israel and Lebanon for several months and returned to find the Voice even worse than it was when I had left. Three months later, after the new editor Felker had appointed refused to publish several of my stories, including one on the month of rehearsals Dylan held at the Bitter End for his upcoming Rolling Thunder Tour, I resigned.

Two years later, in 1977, I was assigned to write this piece on how Rupert Murdoch had taken over New York Magazine, The Voice and New West Magazine from Clay Felker.

Murdoch was new to the United States and wouldn’t become a citizen until 10 years later when FCC rules required that only U.S. citizens could own broadcasting companies. He wanted to buy a small network called Metromedia that he would turn into the Fox Network, so with the help of his friend the president, Ronald Reagan, Murdoch raised his right hand and swore allegiance to his new country.

It was all uphill for Murdoch from then on, and downhill for the rest of us. That year, for this story, I interviewed him at his apartment one night after he got off a flight from Sydney, Australia, where he owned a large chain of newspapers. The interview lasted three hours. I already knew the answers to most of the questions I asked him, because a member of the board of New York Magazine Inc. had given me the corporation books. Apparently having been informed of this, Murdoch sat there with a kind of Cheshire cat smile on his face and answered all my questions truthfully.

I didn’t see him then in this way, but looking back, I now realize that Murdoch landed in the United States and went looking for wounded people who had a history of shooting themselves in the foot and found his first victim in Clay Felker. This is the story of Clay Felker’s shot foot and how Rupert Murdoch stomped on it. As we all know by now, he’s been stomping on the foundations of American democracy ever since.

Part One

Late afternoon, the 22nd of July, 1976. The staff dining room of New York Magazine, Inc. Around a large conference table are seated nine of twelve NYM Inc. directors and the company's vice president for finance. The company's three properties -- New York Magazine, The Village Voice, and L.A.-based New West -- are perceived as hot, flashy, successful. But for months, the New York journalistic community has buzzed about the moving force behind NYM Inc., its Editor in Chief, Clay Felker, a man who at 51 can boast that in nine short years, he turned the dead logo of the old Herald Tribune Sunday Magazine into a live empire, a man whose reputation in the publishing business is exceeded only by his good friends Kay Graham, owner of the Washington Post, and Dorothy Schiff, the owner of the New York Post. On this day, he is riding the crest of a new wave. His latest venture, New West, has, according to his own publicists, "broken out of the gates like a Brahma bull." If his rivals sometimes see him as Citizen Kane, he knows he is the new Henry Luce. He is the toast of both coasts. When he walks into Chasen's in L.A., tables literally turn. At Elaines, while he wolfs down his fettuccini, writers tap at him like woodpeckers. He is the Concorde of the New Journalism. Everybody wants a seat.

So why is Clay Felker crying?

Indeed, right here inside the wood paneled walls of his staff dining room, with executive chef, Felipe Rojas-Lombardi toiling away at $25,000-a-year, a fortune in those days, in the kitchen, Clay S. Felker is standing before a quorum of his board of directors with tears in his eyes. His hands are resting on the table before him. His graying, thinning hair is disheveled. His Saville Row suit is sagging like a damp t-shirt.

"You don't understand!" he screams at his board. "You're all rich! You're rich kids! You grew up rich! You've all got houses in East Hampton! You don't know what it's like to come up from the bottom! You don't know what it's like to come from Webster Groves, Missouri, and make it in New York!"

Felker's voice is a high-pitched whine; he knows he has failed to move the board, and they sit impassively, watching their chief executive officer make a fool of himself. No one says much. They have heard it all before, and they’ve watched his tears flow. Clay Felker wants a raise. He'll quit if he doesn't get it.

Felker didn’t quit. He didn’t get a raise, either. Instead, in a two-week frenzy between Christmas of 1976 and the New Year, Felker lost his empire to Rupert Murdoch, 48, scion of a wealthy Melbourne, Australia publishing family and owner, presently, of 85 newspapers and two magazines. Ironically, Murdoch is the man Felker always wanted to be: a businessman who didn't make news but published it. Felker lost because he ran into someone as obsessed by power as himself and who was infinitely better at wielding it. To win the battle over NYM Inc., Murdoch had some help from Clay Felker himself. One NYM Inc. board member recalls, "Clay Felker was the only executive in Manhattan with a self-destruct button on his desk."

Felker’s life was journalism, but a peculiar Felkeresque kind of journalism that dominated the magazine style of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. As an editor, he had a Madison Avenue knack for “now,” a nose for the essence of the present tense. He conceptualized the go-go years before they went. He peeked through the Swiss cheese of the radical libbers and saw chic. Everywhere he looked, he saw people just like him: people who wanted a raise.

Felker knew that readers no longer had time to read, so he created a collapsible magazine full of disposable information. People save The New Yorker. No one saves New York. The first issues of New York were jammed with the kinds of punchy, personal pieces that would become synonymous with the New Journalism: Gloria Steinem with Mayor John Lindsay on the night Martin Luther King Died. Jimmy Breslin on Living in the Golden City; Albert Goldman on Mel Brooks and Lenny Bruce; Caterine Milinaire on Fashion From the Streets; Tom Wolfe on New York Accents; Gail Sheehy on Teenage Junkies. The features were big, fast and sometimes even good, but Felker sensed they were far from enough. In early 1968, New York was in the midst of a $1.5 million refinancing, and investors needed something to hang their bucks on. With the May 20th issue of that year, Felker turned New York into a how-to guide for the upwardly mobile. Three features dominated the front of the book: “Appraising the Most Expensive Apartment Houses in the City;” “The Decline and Fall of the Chocolate Malt;” and “The Gallery of the Year.” Also introduced was the “Passionate Shopper” column, soon to become a mainstay of Felker’s approach to his magazine. In the pages of New York, the world was on sale, and the sale ended Thursday. New York went beyond slick. It was fast-food information. Every issue of New York gave you just enough to get through next week’s cocktail parties. For 10 years, Felker was the best packager in the journalism business.

* * *

“It’s the end of an era,” said Robert Towbin, investment banker and NYM Inc. board member, after the smoke had cleared and Rupert Murdoch was the new owner of the New York Magazine empire. “I saw Gael Greene (the New York restaurant columnist) at a party the other night, and she pointed at me and said, ‘That’s the guy who sold us out! Towbin!’ Hell, we didn’t sell anybody out. We were bought out by Rupert Murdoch, and so was Felker. The really sad thing is this: It didn’t have to happen. Clay could have had 12 good friends on his board, and together we could have withstood any kind of hostile takeover Rupert Murdoch brought against us. In the end, we weren’t even people anymore. We were only what we could do good for Clay, or bad against him.”

“We were the prisoners of Felker’s image as an editor and publisher,” recalls Carter Burden, City Councilman and former majority shareholder in NYM Inc. “He used his image in the media as a kind of psychological blackmail against us. He was always threatening to quit, and we really couldn’t face the idea of the company without him. But you know something? I think he ended up as much a prisoner of his image as we were, and that’s what Murdoch saw and took advantage of.”

* * *

For 10 years, Clay Felker had us all fooled. From the outside he looked like a genius: a brilliant editor, a powerful publisher, a successful businessman in he world of Big Time magazine publishing. Because his obsession with power was reflected week after week in the pages of his magazines, he appeared powerful himself. He could command by-lines like Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, Mario Puzo. His name kept appearing in salty little column items: lunch with Governor Jerry Brown of California; evenings on the town with investment banker Felix Rohatyn; openings with Washington Post owner Kay Graham clinging to his sleeve; nuzzling “frequent companion” and best-selling author Gail Sheehy in the pages of People magazine…

Felker floated his image the way a city in debt floats a bond issue: with hustle, hype, and other people’s money. And he did it by keeping secret those little truths about himself and his business which would have blown the whole thing up. Felkerism was a dream of instant success and stardom.

For a long time, it worked. People believed in Clay Felker’s successful image because they wanted to believe in the dream his magazine was selling: the pleasures of success and money. Those who truly believed in the man and his dream were the beneficiaries of those pleasures. Careers were born in Felker’s pages. When he lost some of his regular heavies like Jimmy Breslin back in 1971 over a brouhaha about editorial policy, he started a star system and made somebodies out of nobodies. But Felker’s dream was bigger than his stars. His dreams of a publishing empire were an extension of the modern American Dream, the belief that hustle, hype, and promotion are all that really matters.

In recent months, reality began to intrude. The feature pages of New York and New West were padded with book excerpts like “The Me Generation,” and “Good News about Sex.” Felker was having problems getting the kind of nuts and bolts features that had made the reputations of the writers who had left his stable over the years. For many reasons, practical as well as philosophical, the best of his writers simply didn’t want to work for NYM Inc. anymore. To get Norman Mailer’s piece on the CIA, Felker bid $15,000 at a “literary auction” arranged by Mailer’s agent, beating out Playboy and Esquire. Felker’s editorial expenses averaged 18 percent of gross revenues. The industry average, according to the Magazine Publisher’s Association, is 11 percent.

In 1974, Felker bought The Village Voice. He turned the downtown paper that served as a kind of court of last resort for American journalism (the Voice ran many New York and New Yorker rejects over the years) into a tabloid People in newsprint. He filled the Voice with quickie whack-ups, puff-pieces on the star of the week. Felker opted for rock and roll, movie stars, and lifestyle pieces because he thought he could compete with Rolling Stone. He was wrong. A reader survey he commissioned in late 1974, six months after he put his stamp on the paper, was suppressed and then ignored by Felker. Voice circulation fell 20,000 from 150,000 when he took over the paper and rose to 140,000 in 1975. According to Rupert Murdoch, who perused the Voice books after he took over NYM Inc., the only reason circulation went up was because “Clay was virtually giving away subscriptions.”

Similarly, New West was a carbon copy of New York, pitched at the West Coast and incorporating many columns and features already published New York. It wasn’t a brilliant editorial idea. It was Clay Felker’s Rolling Clone.

According to figures I got from one of the NYM Inc. board members that were later confirmed by new-owner Rupert Murdoch, the year before Felker took over the Village Voice, the Greenwich Village tabloid was twice as profitable as New York, with pre-tax earnings of over $1 million a year. New York’s pre-tax earnings were $531,141. According to Murdoch, six months after Felker took over the Village Voice, the NYM Inc. earnings, including the Voice, were less profitable than the Voice had been alone, before Felker bought it.

In 1975, the first full year that NYM Inc. owned the Voice, the paper will have pre-tax earnings of only $500,000, half of what it earned before he took over. NYM Inc. after-tax income for that year represented about three percent of gross revenues. That year, NYM Inc. took in $18.6 million, but its operating expenses were $17.5 million.

* * *

There is another side to all this, of course: Felker’s side. For Clay Felker, spending was a way of life. As he explained the business of NYM Inc. recently, “I wanted to build rapidly and plow profits back into growth. This was the thing which was driving me crazy. We were in a phase of rapid, significant growth, and it was important for us as a company to spend three to five years of devoting resources to this kind of growth.”

And so Felker spent. And spent. And spent. Figures I got from Rupert Murdoch for 1976 expenditures for New York Magazine and The Village Voice are representative of what Murdoch called “the equation in Felker’s head between spending and growth.”

In 1974, when Felker took over the Voice, he announced that within one year Voice circulation would increase from 150,000 to 250,000. Claims for New York were not as grandiose, but he promised to increase circulation there, too. So, let’s take a look at the growth Felker achieved against his single most important area of spending: editorial salaries and expenses.

In 1976, Felker spent about $2.5 million on editorial salaries and expenses, an increase of about 15 percent over the previous year. For his money, Felker received a whopping 2.7 percent increase in circulation and held pre-tax profits steady at their 1975 levels.

For the Voice, Felker spent about $1.4 million on editorial expenses and salaries for 1976. This is also an increase of about 15 percent over the same costs for 1975. Felker’s spending realized a 10 percent gain that brought Voice circulation back to what it was when he bought the paper two years earlier. His increased spending got him a pre-tax earnings gain of only 10 percent.

Again according to figures from Rupert Murdoch, the gain in circulation was almost completely attributable to a give-away subscription panic the company dove into late in 1976. The subscription deal offered the weekly Voice at only 17 cents per issue while newsstand prices were 60 cents. NYM Inc., according to Murdoch, ended up with only one cent per subscriber copy, a total of 52 cents per subscriber for the year.

“Felker got caught in a famous trap in the publishing business,” said Edwin Fancher, for 20 years the publisher of The Village Voice before Felker fired him a month after he took over the paper in 1974. “His ego was completely involved with growth in a Madison Avenue image sense. To Felker, growth was expanding, blowing up the Madison Avenue balloon. He was much more interested in appearing successful than in real success itself, the numbers on the bottom line.”

In 1975, the last year that NYM Inc. turned a profit, Felker earned three cents for every dollar he spent. According to Rupert Murdoch, the man who took over Felker’s empire, it was Felker’s desperate attempt at empire building that brought him down.

“I guess,” Felker reflected, “the beginning of the end for me was when we bought the Village Voice.”

To Be Continued

From day one Rupert Murdoch engaged down market tactics. Appeal to every man’s prejudices not in a loud way but enough to keep his audience. He knew that the masses wanted red meat and a cause to Pursue He trashed the dignity of politics and chased scandals that could keep revenue high for years at a time. On TV he gave the audience sensationalism and often misrepresented facts cheating his viewers by selling them distortion and outright lies. In 2023 much of the media and the public have realized FOX is poison to a responsible society. Perhaps in 2024 we will see the last gasp of Trump and FOX and Murdoch? Maybe.

Great article Lucian you bring such detail and illuminate the past brilliantly. Thank you,

In the early 1980s I was interviewing John Travolta in the restaurant at the UN Plaza hotel. At one point, Travolta sees Felker (didn't he own New York magazine when it published "Saturday Night Fever"?) and says, "watch this." Travolta got down on all fours, snuck up to Felker's table like an affable big pup, just to surprise him. Then Travolta came back and we continued our chat.