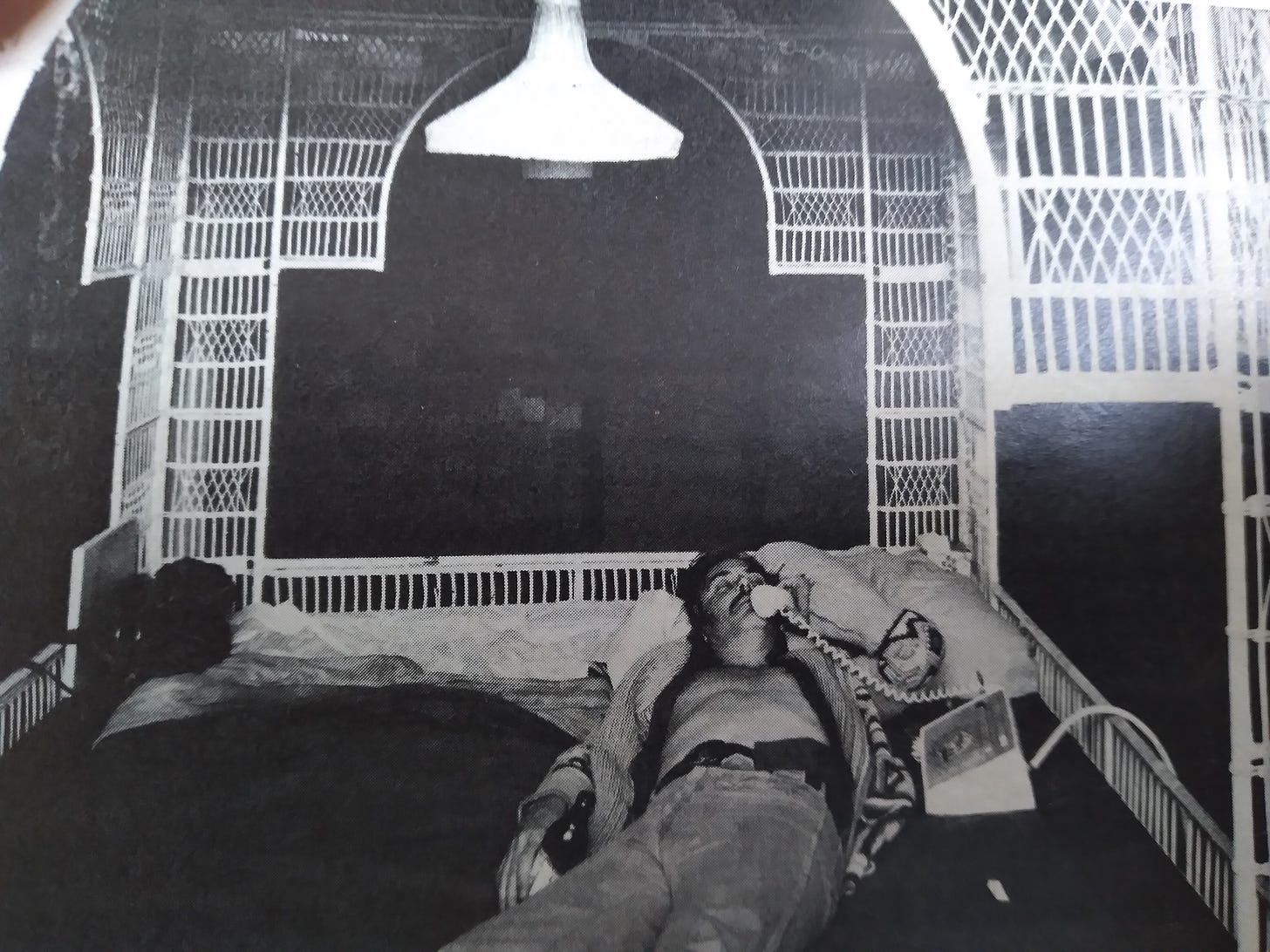

Gary Kellgren felt shitty. He was lying on a bed in the “Rack Room” of the Record Plant in Los Angeles in the summer of 1977, the multi-million dollar recording studio of which he was half-owner and creative genius, the place out of which the hits – “Hotel California,” “New Kid in Town,” “Isn’t She Lovely” – just kept on coming. And that morning at 3:00 am, as he did every other morning at 3:00 am, Gary Kellgren felt just terrible. He was lying on his back in the middle of a king size bed with his left arm flung across his forehead and had left word with the security desk that he would receive no visitors. Still, four solicitous friends conned their way past two guards and three locked doors and arrived in the Rack Room to find Gary pissing blood.

Gary pissed blood in a little bathroom just a few feet away from the king size bed, then he returned to his horizontal position only to rise again a few minutes later to piss some more blood. It was a painful sound, echoing through a narrow opening in the bathroom door…splat… pause…spat…irregular and suspenseful. It made everyone in the Rack Room nervous, but nobody did anything. They just sat there and watched Gary stumble from bed to bathroom to bed to bathroom, pissing blood.

His shirt was open to the waist, and in the dim light of the Rack Room, Gary’s chest was bony, pale. His salt and pepper head rested on a huge wooden roller, around which was coiled about 30 feet of thick hemp rope in the manner of a medieval torture rack. Gary’s eyelids hung at permanent half-mast, and his eyes had a dull finish, like varnish gone yellow. His spindly arms protruded from a brown print Qiana shirt and lay on the patchwork velvet bedspread like stains in the fabric. He was so wasted he made Mick Jagger look like Arnold Schwarzenegger; so gray he made Keith Richard look like a Beach Boy. His right foot tapped the air slowly, a count off the beat of the music that seeped into the room from speakers mounted above the bed. The music, in contrast to the bizarre surroundings, was what they called the “mellow sound.” Occasionally, Gary’s eyelids closed completely, his right foot stopped tapping the air, his chin fell to his skinny chest, his arms seemed to sag and got even thinner, and he looked…dead.

The people around Gary were very concerned. Their voices constantly whispered: “Gary, are you all right? Can we get you anything?” There was the voice of an A&R man for a major record label, and those of three women, or girls, actually. One of them, a darkly attractive Chinese-American; another a short brunette wearing a macramé top showing her unblushing nipples and aureole; the third a skinny blond with the squeaky gum-cracking voice of a 13 year old. They kept whispering to each other about how little sleep Gary had gotten over the past week, how long it had been since he ate anything, whether or not he wanted another Coors, another bottle of Calistoga water, another pill…

Indeed there was about the scene that surrounded Gary Kellgren on that night an atmosphere of reverence. We were in the presence of one who had made a lifestyle of suffering. Gary didn’t just feel shittier than the rest of us; he felt shitty FOR us. He seemed to have taken upon his narrow shoulders the entire weight of the old rock and roll ethic, the sensibility which demanded that you live life right out to the edge, that you take every chance, do every drug, experience every high, dig every low, keep yourself awake every possible moment until you finally crashed and reached the state of new bliss, the perpetual hangover.

Gary Kellgren had been hung over for years. Thirteen years, to be exact, in the rock and roll business…thirteen years of hassles, man…thirteen years of making hits and bucking those forces you couldn’t see…thirteen years of fighting off that little army of straight gnomes who are always ready to fuck things up. And all for what? For another night in the Rack Room? Another night spent Puzzling Out the Problem, Dreaming the Dream…how do you make the Record Plant bigger, make it better, make it the only recording studio anybody who is anybody would want to record in, the Last Recording Studio on Earth, the place that will contain Gary’s rock and roll dream, a dream of rock as the lifeblood of the New Hollywood, the thing that will keep all the other dreams alive, preserve the true spirit of Hollywood, a spirt of fantasy and magic…why, you remember the spirit! It was the heart of the Wizard of Oz: get to the Wizard and all your dreams come true! It was like that dream of childhood, that terminal kid-thing present in the game of Three Wishes. Every kid, at least once, tried the most obvious first wish, that all your other wishes would come true! Well, that was the rock and roll dream, really, and it was Gary’s dream. To achieve it, Gary cast himself in the role of the Wizard, the Man to See, the Man Behind the Curtain pulling the levers, running the machines. But somehow it had gotten twisted. Somehow Gary ended up in the Rack Room pissing blood.

He was up! Sitting, now standing on wobbly legs, Gary grimaced and everyone grimaced with him. His left arm rose, and their eyes followed it as if he were a magician holding aloft a scarf. Gary grimaced again, opened his eyes fully for the first time in hours, squinted across the room and waved his arm as if sweeping aside a curtain. He was trying to say something. Everyone sensed it and waited. No one dared move for fear they would break Gary’s fragile concentration. Gary’s face, usually an impassive mask, contorted into a fierce sneer.

His hands moved in quick, karate-like chops, then they stop. Gary was peering between a narrow slit formed by his hands…stiff and knife edged. His right hand circled slowly to the side, then down. At the bottom of its arc, his hand formed a fist and jabbed sharply up, like an uppercut.

“Vision,” said Gary in a throaty authoritarian rumble. His right fist hung in the air, then circled down and jabbed up again and again to punctuate his words: “New-jab-vision-jab. Look-jab-at-jab-the-jab-business-jab-man! Chrome-jab-steel-jab-stainless-jab-steel. Only-jab-business-jab-shines. Rock-jab-is gone-jab!”

Gary swallowed the final word like a Quaalude. His fist was hanging in the air, and he gazed slowly around the room, grinning. Heads nodded in silent agreement. Gary just explained the Death of Rock. Unlike the businessmen who run rock and roll, the media who suck it dry, Gary had no excuses. He looked like he’s about to die because he understood that rock and roll always meant you could never grow old. Gary was 38. His face twitched in handsome agony.

One of the girls helped him to the bathroom to piss some more blood. The other girls tip-toed from the Rack Room. Gary might crash, they whisper. It was 5:00 am, and for the first time in more than two days and nights, Gary Kellgren looked like he might get some sleep.

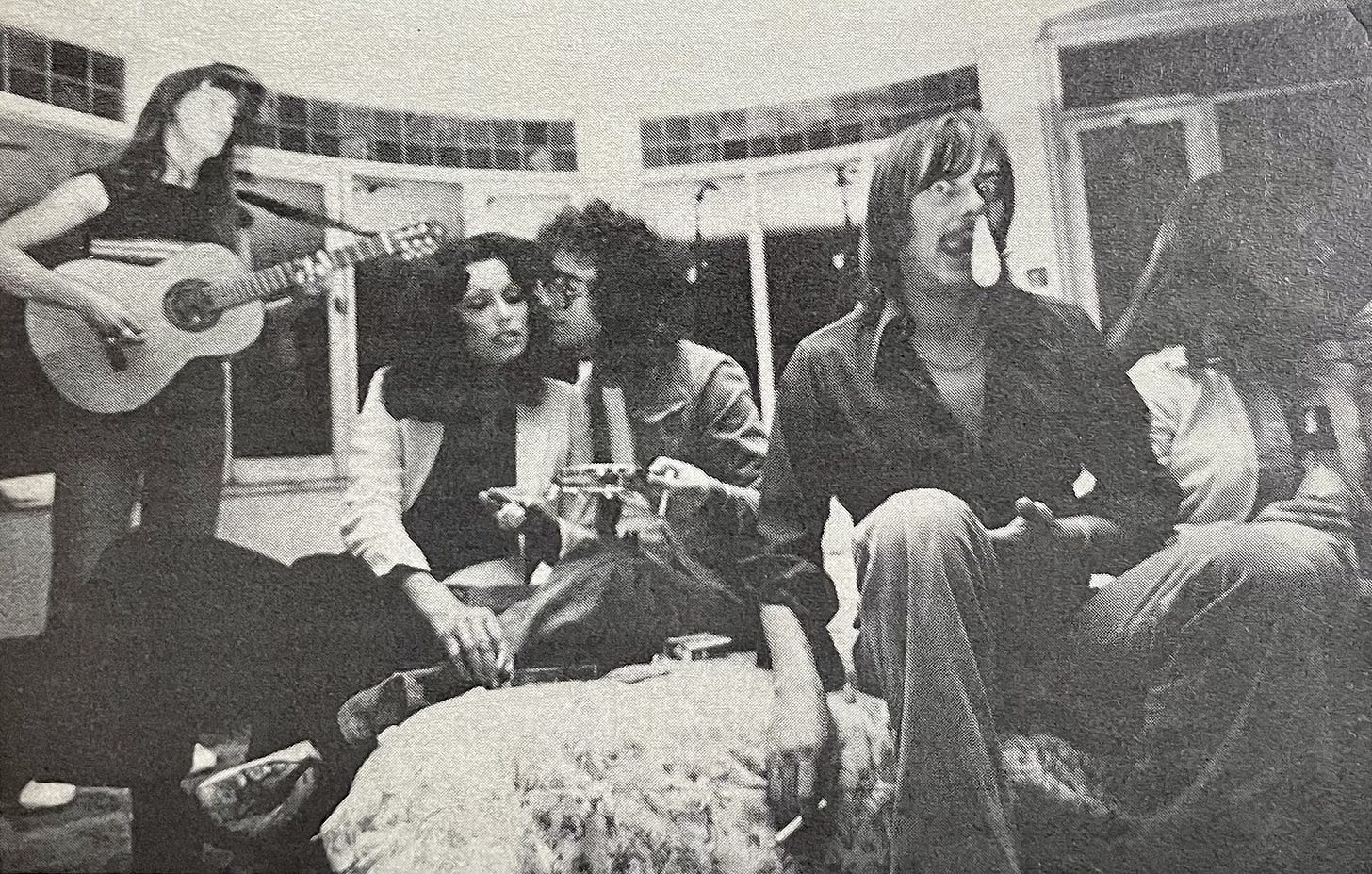

Twenty-four hours later, Gary was in Studio A of the Record Plant. He seems rested. He just came from the Rack Room, where for two hours he was drinking Coors and reading Billboard and consulting the Record Plant schedule. As usual, all four studios were booked nearly around the clock. At that very moment, Bette Midler was working Studio B, and Frank Zappa had set up a second home in Studio C. The Eagles and the Tubes were recent departures, as were Dave Mason and Bill Withers. The Record Plant was so popular that some groups used the Rack Room, the Sissy Room, and the Boat Room, with a nautical motif, like motel rooms. There was also another room they jokingly referred to as the Anne Frank Room, because it contained a hidden cubby-hole beneath a loft bed. The Eagles’ hit single “Hotel California” was written about the Record Plant, with its famous refrain, “You can check out, but you can never leave.” It seemed possible to enter the huge Hollywood complex and never return, the place had such a vortex-like quality built into it at Gary’s design.

“I opened this place in 1969,” Gary said, standing in the middle of Studio A, bringing to mind the image of him in the “Hotel California” lyric, “So I called up the captain, please bring me my wine, he said we haven’t had that spirit here since 1969.” “Eight years ago, this studio was the only one of its kind in the world. We had a party here in this very room. Princes and princesses, pimps and aristocrats, dealers and movie start, all of them came to the opening of the Record Plant. It was like the beginning of the dream I started back in an old warehouse off tin-pan alley in New York: the idea that a studio is your home because it’s my home, too. I stayed up for a whole year, 1969, working on this place. That’s what you have to do to make it in the music business. You work six days a week, and then on the seventh day, you keep on working. It’s beyond a god trip, man. You want to make it in this business, you do the same thing the stars do. They’ve got to be on top of their image thing, the studio thing, the performance thing, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, all year long. People think rock and roll is what they read in Rolling Stone. People don’t know shit.”

Bob Margouleff joined Gary. He had just finished co-producing Billy Preston’s latest album, and was credited by those in-the-know with having for being the genius behind the scenes on Stevie Wonder’s monster album, “Songs in the Key of Life.” But Margouleff dropped by the Record Plant for the same reason the place was a hang-out for members of the Rolling Stones, for ex-Beatles, for Eric Clapton, for Stevie Winwood. The heaviest rock and rollers came to the Record plant because its studios have a certain sound they were looking for, and they came because of Gary Kellgren. Gary not only had “ears,” he had ears. Christ Stone, Gary’s long-time friend and half-owner of the Record Plant, knew about Gary’s ears. “I was there when he recoded Barbara Streisand, Paul Anka. He recorded Anka for years. Everything he touched in the studio was a hit. Gar is remarkable in the studio. He is like a secret Phil Spector.”

Producer Margouleff brought two tapes with him, cut by groups he produced and managed. He wanted to play them for Kellgren, and would wait expectantly for his response. The first was a soul/disco group, pumped up with strings, synthesizers and electronic effects that pushed disco into a kind of modern Young Rascals sound. Kellgren closed his eyes and nodded his head. After two cuts, he raised his hand. That was enough.

Margouleff scrambled to play the second tape. He wraped the wide 16-track tape around the idler wheels and tape head of a master machine and punched a button and the big Westlake Studio Monitors (designed by Kellgren and Tom Hidley) played a country rock tune. The music was an undistinguished hybrid of early Byrds and modern “outlaw” country. Gary does not move. The song finished and Margouleff pushed a fast-forward button. The monitors screamed as he searched for another cut. A second country rock tune, this one more Eagles-influenced. Less than a minute into the song, Gary got up from his reclining leather producer’s chair, walked across the control room, and punched a large red lever marked “STOP.” He walked back and flopped into his chair. He ran both hands through his graying hair, looking tired again. “This music isn’t saying anything to me,” he said. The tape rewinds with a soft whisper. Margouleff had a look of resignation on his face. The next day, he would fly to Indianapolis to pick up a Lamborghini Countach. On this night, he claimed not to be surprised by Gary’s blunt comment. “That’s why I came over to play the songs for, man,” he explained. “One listen from Gary can save you thousands and thousands in studio time.”

Gary Kellgren existed in a sphere of pure sound. He always did. Engineer Jimmy Robinson was with Kellgren in the early days before the Record Plant. “Gary had a dubbing studio around the corner from 1619 Broadway, the Brill Building,” Robinson recalled. “Everybody from 1619 used to come over to cut demos with him. Carole King. Neil Diamond. Paul Anka. The whole early 60’s rock and roll scene would be there. Neil Diamond would be up in 1619 in his little cubicle, and he’d write five songs, and he’d run around the corner to Gary’s studio, and he’d put down $50 for 30 minutes of studio time, cut five tunes backing himself on guitar, run back around the corner to 1619 and sell the songs for $50 each for a $200 profit. Then Gary opened up a regular studio, with like, a two-track tape system, the early days of stereo. But he was never satisfied. All the studios were like bare rooms with green paint and linoleum floors. It was like making music in a hospital ward. So finally, in 1967, he got together with Chris Stone, was working for Revlon, and this heiress to the Revlon fortune. Stone was the businessman, Gary was the engineer, and the lady was the bread. When they built the first Record Plant, it was like a rock and roll spaceship.”

Gary wandered from one studio to another in an almost sleepwalk state, shuffling along in loafers that were one size too big, so he could slip into them without reaching down and spending the extra energy to pull them on. Nothing mattered but the sound that was being produced in Studio A, Studio B, Studio C, Studio D. Every room could be completely closed-off, darkened, turned into a capsule in which there was no day, no night, no input other than that which was created by the musician in residence. Gary specialized in creating environments in which musicians could work at the top of their game. Studio B in the L.A. Record Plant was created specifically for Stevie Wonder. One of the studios in the Sausalito Record Plant, a place known as “The Pit,” was built specifically for Sly Stone. Kellgren’s reputation as a sound engineer knew know bounds. He was the first engineer to invent “phasing,” an electronic signal modifier that produces a jet-type sound from a guitar. Until that point, recording had a one-dimensional quality. Gary experimented constantly. He changed rock and roll. His reputation was built up, little by little.

Jimi Hendrix was in one of the Record Plant studios, blocked. He wanted to create a sound, a specific sound just like this – he pursed his lips and out came a high-pitched wheeze, almost a whistle – and nothing he did on the guitar could produce that sound. Gary appeared. He listened to Hendrix’s pursed lips. Hendrix explained he wanted to re-create the sound he heard in his ears when he jumped out of an airplane with the 101st Airborne Division when he was in the Army. Gary’s ears focused on the wheeze, exactly what the wheeze sounded like. He disappeared into a workroom. After a while, he reappeared with a small metal box. Inside could be seen resistors, transistors, capacitors, endless little electronic gadgets. Into one side of the box, he plugged Hendrix’s guitar. Into the other side, he plugged the lead to the amp. He told Hendrix to strum a certain chord. Gary picked up the box and adjusted a small knob. He told Hendrix to strum the same chord again. The amp blasted the wheeze. Only moments ago, Hendrix was wheezing through pursed lips. Now he wheezed with the strum of a chord on his guitar. His block was broken. Gary disappeared. Hendrix went back to work.

The first monster hit album the Record Plant produced was Hendrix’s “Electric Ladyland.” (When Hendrix died, Gary turned over 80 tapes of Hendrix’s outtakes…1,200 hours of Jimi…to the Hendrix estate.) The first hit single recorded at the Record Plant was “Don’t Bogart That Joint,” by the Fraternity of Man. Hundreds of rock starts have plugged into the Record Plant consoles since then. All of Ringo Star’s L.A. hits were recorded there. The place was a second home to groups like the eagles, starts like Rod Stewart. When the Concert for Bangladesh was taped, it was to Kellgren the heavies turned as engineer to master the recording. He engineered and produced hits for Ron Wood and Bill Wyman (Stone Alone). Even if he had done nothing else in his life, Kellgren would be famous among musicians for a jam he recorded in 1975, a never-released song called “Too Many Cooks.” Present for the session were John Lennon, Stevie Wonder, Billy Preston, Mick Jagger, Al Wilson, Harry Nilsson, Jim Keltner, Ringo Starr and Danny Kootch. The song was aptly titled. At one point, Jagger expressed displeasure with the way things were going. Gary reportedly told him to “sit on it.”

You get the sense after a while that Gary Kellgren’s command of the technological milieu he dominated put him out of reach of conventional adulation. Gary figured fame out. To him, fame was a series of boxes, one within the other. The biggest box was the fans. They were constantly trying to get inside the next smallest box, which contained the rock stars. The fans want to get backstage, they want to be in the rock star’s hotel room, they hunger at the door of the studio. But there was another box, inside the box containing the rock stars. It was a box the fans didn’t even know about. The box was the Record Plant. The box contained Gary Kellgren. He simply laid there every night on his back in the Rack Room or the Sissy Room waiting for the rock stars to knock on his door, waiting for his multi-line mega-phone to buzz.

Sooner or later, it happened. This one wanted a favor. That one wanted Gary to listen to his latest cut, listen with those Ears to see if the horns needed to be brought up a little, if the bass could use more BOOM. They came to the Record Plant and paid for Gary’s marvelous machines and they paid for his Ears and they paid in the true currency of celebrity: cash.

Kellgren’s groupies were rock stars. His Record Plant was the small intestine in the digestive system of the rock and roll business. His machines broke music down into its nutritional components, they turned sound into electrical energy and placed it on electromagnetic tape, from whence it was transferred onto plastic discs, where it was picked up by diamond styluses and became electrical impulses once again, which were amplified through speakers, pushing air molecules into motion, which is what the musicians played to begin with. The Record Plant’s marvelous machines turned rock and roll into ear food for the masses, and Gary Kellgren was the appendix of the music. He just laid there and absorbed the poisons.

Self-indulgence and abuse of his own body were Gary’s way of life. The by-product was thinness, a measure of dedication. Fucking with technological systems and with your own body became synonymous. Gary was not alone. It wasn’t uncommon to visit one of the restaurants frequented by actors, actresses, singers and musicians in Hollywood and find someone in the stall next to you with a spoon up the nose or a finger down the throat, throwing up a meal just shared with an agent. Such was the premium placed on indulgence and abuse that the constant sniffle of the cocaine cold, the sound of up-chuck, and the ringing of the telephone were the sounds of the Hollywood struggle. Gary often hung up the phone after a long, stage-whispered conversation and announced to those who surrounded him on the bed in the Rack Room, “Jesus, that chick gives great phone.”

The next morning, since nobody else would, I took Kellgren to the emergency room at Cedars Sinai. When he emerged a few hours later, I drove him back to the Record Plant, and there, sitting on the bed in the Sissy Room in the company of two rather brutal looking guys from East L.A. who had come bearing condoms filled with cocaine, Gary described his visit to Cedars. “Turns out I’ve got a kidney stone, man.” He is unusually talkative and excited, sniffling from ingesting the shiny white powder. “I should have figured what it was, with all the blood I’ve been pissing.” It was pointed out that a kidney stone had become a minor medical matter, requiring only the administration of a drug that dissolves the stone, which is passed from the body in urine.

“Yeah, the doctor told me about that, but I’m not taking it. I told him, forget it. I want to be cut.” One of the guys from East L.A. was visibly agitated at the thought.

“I already had the doctor book the surgery,” Gary explained, noticing the queasy look on the guy’s face. “I’m gonna have him open me up and cut the little fucker out. He said it’s been in there so long, it’s about the size of my thumbnail. It’s like a ball of calcium, with sharp little edges that cut into the walls of the kidney and made me bleed. I’m gonna have him cut it out and then I’m gonna have a ring made, so when I walk into a room and somebody says, hey, man, that’s a far-out ring. What kind of stone is it? I can hold it up – it’ll have a gold mounting and the doctor said it will look all white and shiny – I can hold it up to the light and say, ‘kidney, man.’”

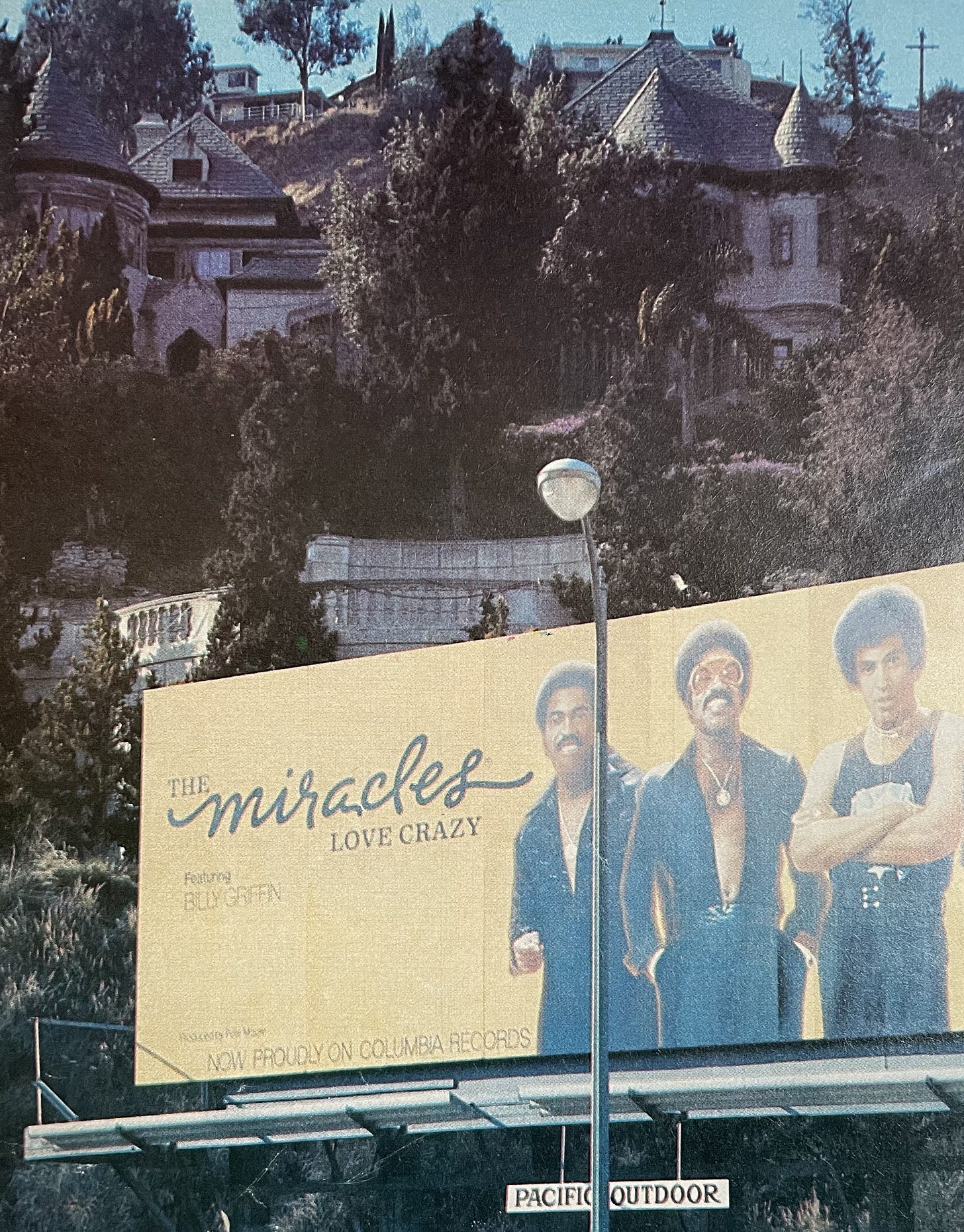

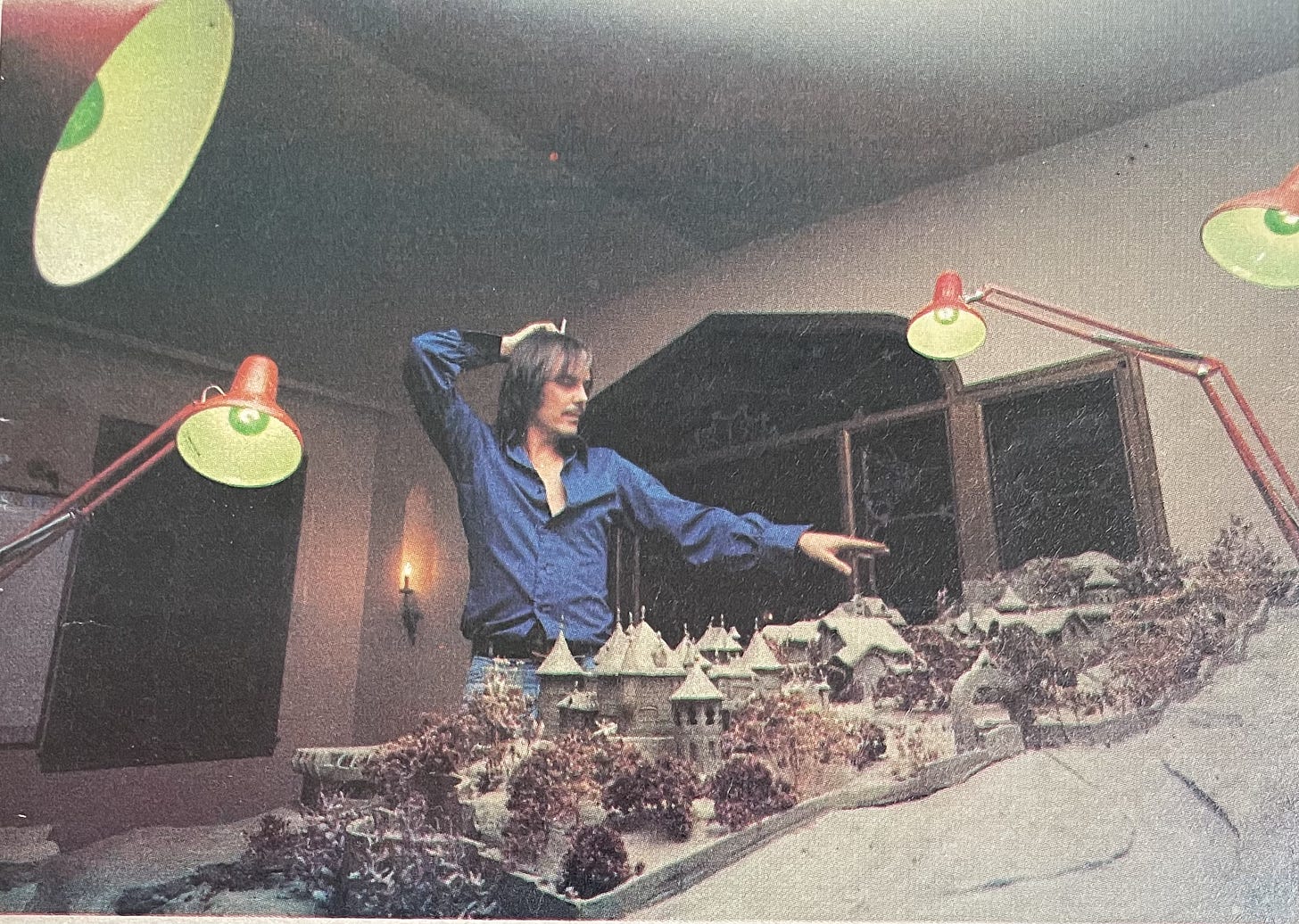

Gary rented a rambling old castle above Sunset Boulevard built in 1929, once owned by Buster Keaton. Noah Dietrich, the top aide to the late billionaire Howard Hughes, owned it before Gary rented it, and today it’s owned by Johnny Depp. But on this night, in the empty grand ballroom, near a 50 foot expanse of leaded windows overlooking the Los Angeles Basin, Gary stands before a large plywood board on which is mounted an exact, to-scale replica of the property. The mansion was set on four acres that ran in a narrow rectangle up the hill above Sunset Boulevard. It was one of the last great Hollywood mansions, and one of the largest pieces of real estate in L.A.

The model was elaborately detailed. Every tree was accurately reproduced and the castle itself was carefully etched in clay, every stone wall and turret carved to scale. The plywood board was slanted, approximating the angle of the hillside land. Above the castle, where now there was only scrub oak and pine, the model showed a medieval village, a collection of thatched roof cottages connected by pathways. The clay model was surrounded by a stone wall, turning the entire hillside into a compound, a fort accessible through a single gate where Sweetzer Street dead ended.

The clay model was built by a well-known architect, and plans existed for the construction of the four-acre fort. The mansion was known around the Record Plant as “The Castle,” after its turreted gothic architecture, and it was Gary’s final obsession. He spent upwards of $150,000 on the plans for what he hoped would be his ultimate vision of the Record Plant as it truly should be: a place apart in time and space from the rest of the world, a sphere in which rock and roll could once again be magical, in which Gary would be undisputed master magician.

But at 4:00 am in the main ballroom of the castle, Gary was alone, pacing its terra cotta floors, lamenting the demise of his dream. For no matter how many strings he pulled, how many friends he called on for help, how many parties he threw at the castle, spinning his vision of the dream long into the night, standing at the model, pointing to its exquisite details, its delicious excess, all of it in the “true spirit of Hollywood” as he explained, no matter what he did or how much money he spent, nothing could bring about the zoning ordinance changes necessary to transfer the castle and its four empty acres from residential to commercial. Without such a zoning change, Gary’s dream for the Ultimate Record Plant was dead. It was that little army of straight gnomes again, nibbling away at his dream.

There were only a few days left on his lease, for which Gary had been paying $4,500 a month. All the furniture had been moved out of the mansion, and the place had a dusty, decaying feel. None of its half-dozen or so bathroom had been cleaned in weeks, and the kitchen looked like something out of a Dennis Hopper movie about the grooviness of communes. Everywhere there is garbage and filth, the silent remains of defeat.

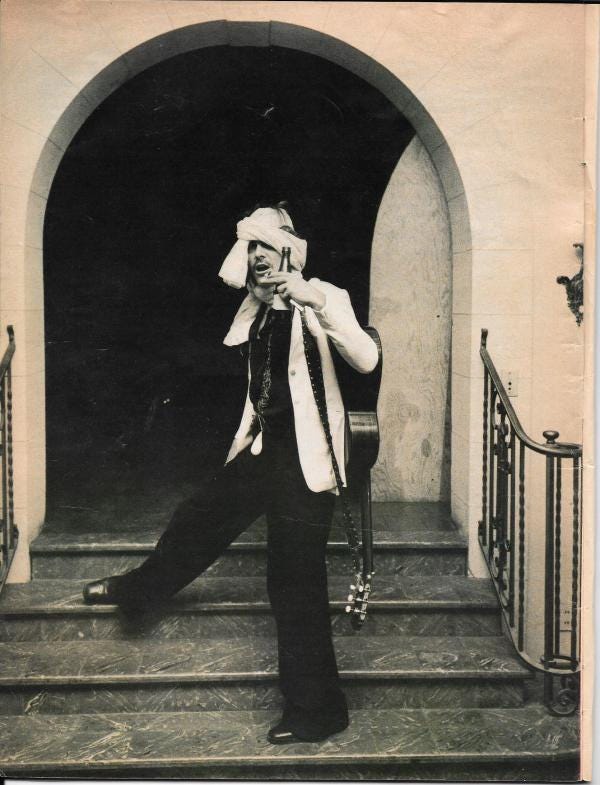

Upstairs, there were noises, a blaring stereo, a television turned up to compete with the music, a final party at the castle. And now Gary and a group of his friends descended a winding grand staircase. He had gotten himself up as a jester…or was he a wizard. A long piece of white silk was wrapped around his head like a turban, and another piece formed a sash about his waist. Hanging from the front of the sash was a condom filled with two ounces of cocaine. In his right hand was a wooden pointer, and in his left, a bottle of Coors. He mounted a platform next to the model of his Record Plant Dream Village. Four green lights surrounded the model, and their hoods illuminated him from the waist down, but not his face, giving his words a weird, disembodied feel. In the empty ballroom with its dirty terra cotta floors, his voice echoed eerily as he cracked the pointer against the plywood base of the model in anger. The pointer came down again and again, the sharp sound of wood against wood echoing through the old mansion like gunshots:

“Debbie Reynolds (CRACK) is behind this thing 100 percent (CRACK),” Gary said, shifting his weight from one foot to another. “She is sitting there (CRACK) with $3 million (CRACK) in furniture and memorabilia (CRACK), including part of the set of the Wizard of Oz (CRACK), starring Judy Garland (CRACK). This is my Emerald City (CRACK), Oz (CRACK) a take-off from the name Ez (CRACK). All I’m trying to do (CRACK) is preserve this place (CRACK), preserve a little of the old Hollywood (CRACK). But I’m gonna lose it (CRACK). And then it’s up for grabs (CRACK). They’ll build some kind of tinsel tower (CRACK) where I wanted to build my vision of the Record Plant (CRACK), turn it into everything it should be (CRACK). Now it’s just going to be pissed away (CRACK), because we can’t get a fucking (CRACK) zoning (CRACK) ordinance (CRACK) changed (CRACK). It’s sick, man (CRACK). Sick (CRACK).”

Later that same night, Gary was back in the Rack Room. It was getting light outside, an occasion that always seemed to depress Gary. He and a young lady were standing in the bathroom going through a process which Gary repeated at least a dozen times a day. He took a glass, added two tablespoons of baking soda, filled it with water, handed it to the girl, instructing her to gargle. She does. When she finished, he added another couple of tablespoons of baking soda to the glass, filled it with water, and he gargled, smacking his tongue against the roof of his mouth. Then he pulled the condom filled with cocaine from the sash around his waist, and with the corner of book of Record Plant matches, he shoveled a portion of cocaine into the mouth of the girl, telling her to swallow it. She did. He took the same quantity on the back of his tongue and with a grin, swallowed it. The girl had a perplexed look on her face. “I can never get used to that stuff,” she said.

Kellgren seemed suddenly agitated, full of energy. It was as if the eulogy for his Emerald City had never been delivered. Resting against the roller of the bed in the Rack Room, he read the latest issue of Billboard. He picked up the Record Plant schedule for the next day and studied it. Then, to no one in particular, with the girl gently stroking his bare chest, he talked about dying. It was a subject to which he returned almost every morning when he knows that outside, the sun has come up.

“When I go, I’m goin’ in class,” he said, his left arm thrown across his eyes. “I’m gonna call a limousine, have it pull right up outside here in the parking lot, and I’m gonna climb in the back seat and tell the driver to take me down to the beach. It’s gonna be one of those limos with the smoked glass, so you can see out, but they can’t see in. I’m gonna sit back there with my feet up, with some tunes on the tape deck, and I’m gonna polish my nails as we drive to the beach. I’m gonna polish and polish them, shine them and polish them until they gleam like chrome. When I go, I’m gonna have Electraglide nails, man, because I can’t think of anything worse than having dirty nails, man. They my nails catch the light, they’re gonna be as bright as chrome. They’re gonna blind you, man. I’m gonna have Electraglide nails when I die. Let those fuckers try to take that away from me, man. Just let ‘em.”

Gary Kellgren died a few weeks later.

This article originally appeared in the August 5, 1977 issue of New Times.

I like to think I’m a good writer. Then I read this brilliance and realize I’m not even close. Panting pictures with words - so beautiful.

Well that was harrowing and all I did was read about it. I cannot imagine actually being there.