It turned out to be one of those experiences that is burned into your consciousness, branding you for life. But its beginning was far more prosaic and odd, when I really think about it. It was the spring of 1966, and I was a Plebe, a first-year cadet, at West Point. We Plebes were not allowed weekend leaves, or any other sort of time off the campus other than for Christmas and the Army-Navy football game in Philadelphia, so time away from the Academy was precious.

But now West Point had qualified for the NIT basketball tournament, and the games were being played at the old Madison Square Garden on 8th Avenue in New York City, and the entire Corps of Cadets was bussed down to the city for the game. I had little interest in basketball – I don’t think I had attended a single game at the Army Field House on the Academy grounds – so when the trip was announced, I figured I could skate out of going to the game and meet my girlfriend and do something I really wanted to do, which was to see Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot, a jazz club on St. Marks Place, a gig he was playing I had read about in the Village Voice.

So that’s what we did. I met my girlfriend, a secretary from Staten Island, on the street outside the Garden and we took a subway down to the Village and walked across 8th Street to the Five Spot, just off the corner of The Bowery. It was a small club, one of those beatnik-era places with tables that seemed no bigger than a dinner plate with a bandstand, if you could call a platform about a foot high a bandstand, up against one wall, and a bar along the other.

It was a rainy night, and my girlfriend and I had gotten there early for a jazz club, probably around 9 p.m. I was in my Dress Gray uniform, because we were required to wear our uniforms to the basketball game, and we were wet from crossing 8th Street from the subway stop on 6th Avenue. Monk’s band trickled in – in think it was a quintet that night – and took their places on the little bandstand, the sax player honking, the drummer practicing fills on his snare, when Monk walked in from the street. He passed right by our table, walked onto the bandstand, shook the rain from his chincey-brim hat and hung his overcoat from a peg on the wall.

Without even looking at the members of his band, Monk took his place at the piano, reached down to the floor next to the pedals and picked up a thick copy of the New York Yellow Pages. He flipped through it for a moment, as if he were looking for a specific page. Apparently finding the page he was looking for, he put the thick book on the piano’s music rest and began to play the first notes of “Epistrophy.” The band kicked in, and they were off.

Seeing Thelonious Monk playing at the Five Spot as an 18-year-old would seem to have been enough of a high spot to remember. But the night was young, as they say. I had to be up on 10th Avenue somewhere in the 40’s by one a.m., so we left the club around midnight just to be sure I would make the bus back to the Academy. Just as we walked out the door of the Five Spot, there was a commotion up the street toward 2nd Avenue. A group of people were exiting The Dom, a discotheque a few doors down. They were talking loudly, almost shouting at each other. It had stopped raining, but the street was still wet, and the lights of the storefronts and apartment windows along St. Marks Place were reflected in puddles and wet pavement. Suddenly, a nymph-like figure appeared, dressed in silver lame from head to toe. It was a young woman. She had silver hair and gigantic silver loops dangled from her ears, and she began to dance in the middle of the street, waving her arms above her head and kicking her legs as if all her limbs were in slow motion.

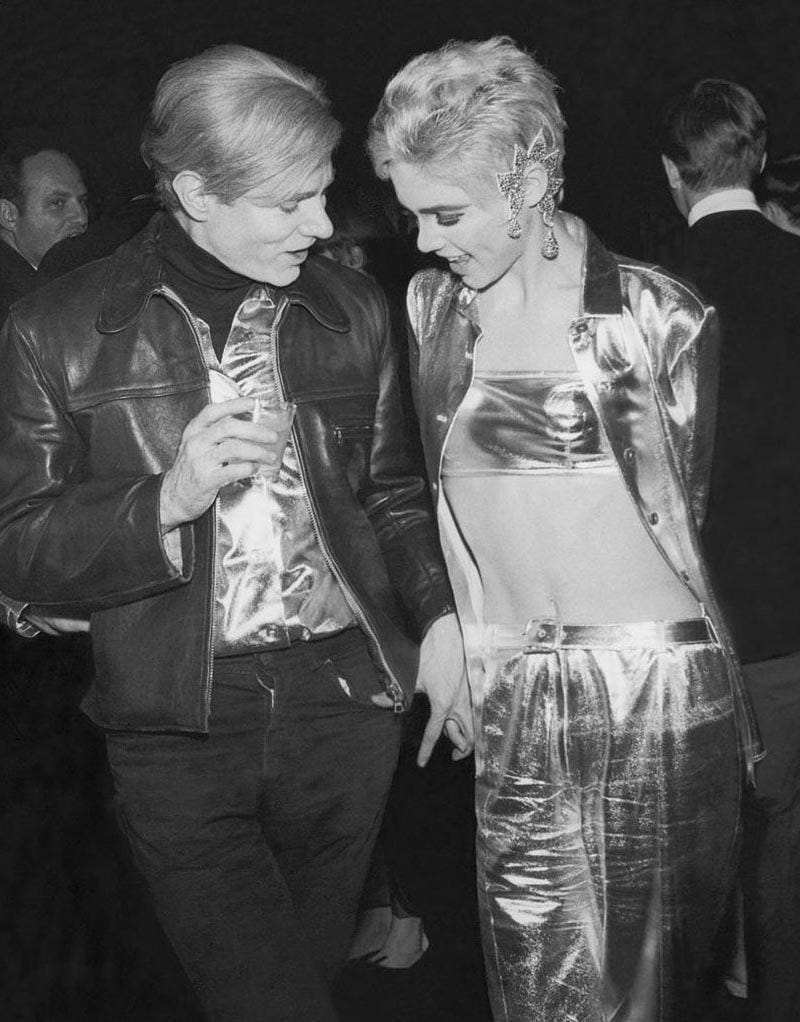

A man in a black leather jacket who had silver hair just like the girl’s was standing there watching, and someone else was calling to her, trying to get her attention as a black limousine pulled up along the curb. But she kept dancing in the middle of the street, spinning slowly, her arms and legs liquid in the lights from above and reflected from the street.

It was like something had escaped from an unseen corner of the night. I knew enough right then to realize that you didn’t see things like that out in the world. As I would come to learn, in 1966, and even in later years, you might see someone dance like the girl in the middle of St. Marks Place, but you had to go to a performance of Martha Graham or Merce Cunningham in a venue like the Judson Church to witness such a human spectacle, and even then, you would see it stripped of the context of that night – a girl alone in the middle of a wet street moving by herself through the lights and the night.

I figured out who she was because I had seen her picture in the Village Voice, and I had seen his picture too. It was Andy Warhol and his first superstar, Edie Sedgwick, who had burst upon the scene the year before. She would die only five years later of a drug overdose in Santa Barbara, California, where she was originally from. But before she went, Edie Sedgwick would become famous for something that with the help of Warhol, she created: She wasn’t a dancer, or a singer, or an actress, but even on that night in 1966, she was famous simply for who she was. She was an image.

What caused me to remember that night and to write this was running across an interview with Edie’s older sister, Alice Sedgwick Wohl, published two days ago in Graydon Carter’s online magazine, “Airmail.” The interview was occasioned by the publication of her book, “As It Turns Out,” by Farrar, Straus and Giroux this month. I immediately ordered the book and consumed it like an ice cream cone on a hot day, and I can confirm that the book is, in the words of the “Airmail” interviewer, Lili Anolik, “a history that is also a present and a future, a brilliant and profound work, and, by the end, an almost unbearably moving one.”

Wohl spends the book remembering her own, and Edie’s (and her brothers’ and sisters’) upbringing on a cattle ranch outside Santa Barbara by parents who were, in a phrase that’s now familiar, not present, allowing, or perhaps more accurately, causing, their children to invent themselves. The mother was a damaged heiress more interested in horses than in children, and the father was a wildly ambitious man – Wohl calls him “priapic” – who after graduating from Harvard with a membership in its storied Porcellian Club that had been passed down through the family, called himself an artist and a sculptor but never really worked a day in his life either on his art or to make a living.

Wohl, who traveled across the country by train as a teenager to a private school on the east coast, and Edie, who ten years her junior was essentially left to fend for herself on the ranch and in a series of mental hospitals her father checked her into to shut her up after she walked in on him fucking her mother’s best friend. He also apparently abused her, although Wohl says she has no evidence other than Edie’s own, often drug-fueled, stories she told others.

The parts of the book about the California ranches – there were two of them after oil was struck on the first, and the father could afford to buy a larger, more showy second one – are fascinating as a glimpse into the secrets of an entirely dysfunctional family of wealth and privilege. But it’s the section on Edie’s time as a Warhol superstar that makes both the “Airmail” interview and the book worth reading (you have to provide your email to access the interview.) https://airmail.news/issues/2022-8-20/super-star-power

Listen to Wohl as she describes suddenly encountering her sister’s image in a visit a few years ago to the Addison Philips gallery at the private school, Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts:

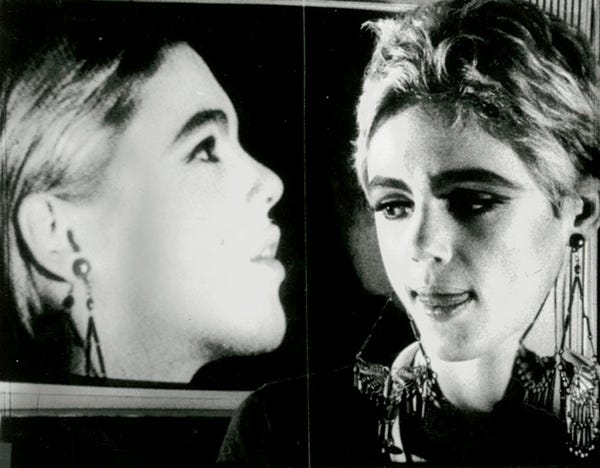

“I remember climbing these wooden steps, by myself, to the top floor. And there, in front of me, on a film screen, were two enormous heads of Edie. On the left was an Edie who was very pale, with silvery hair and a kind of mystical look on her face, and she was speaking slowly, and there was no sound. And then there was a darker head that was smaller and on the right. The Edie on the left was responding to the Edie on the right. And she never stopped moving, talking, smoking, reacting. She was absolutely kinetic. Just so alive, more alive than I’d ever seen her in real life. I couldn’t take my eyes off her.

And when I saw what Andy had made of her—all the layers and dimensions that were at play in this film—I thought, Warhol is a genius. That’s what I thought. And I finally understood that the two of them, together, had set in motion something that we’re living out in the present. I hadn’t understood it at the time, but now, seeing this masterpiece—Outer and Inner Space, it’s called—I did. And I realized that I’d got everything wrong.”

What Wohl had gotten wrong was a life-long assumption that her sister, in all of her glitter and drugs and anomie, had never accomplished anything. “Edie was confined in one way or another until she was 20 years old,” Wohl says in the interview. “Edie was someone who had no inner structure. She had no attributes, no conversation, no education. She didn’t read. She didn’t care. She wasn’t interested.”

But seeing her sister’s image in the film Warhol made of her – his first use of a video camera lent to him by a store that hoped he would popularize it – changed Wohl’s perception. And the interview with her changed mine: “But she was smart! You can tell from the transcript of Afternoon [the 1965 Warhol film starring Edie, Ondine, and Dorothy Dean] that she was picking things up, that she could hold her own. And she was an amazing athlete—a natural rider, absolutely fearless, and a beautiful swimmer. And she had a tremendous amount of charm. It’s why she never learned to function, because she had such irresistible charm she could manipulate everybody to do things for her. Edie was all energy and no outlets. So the energy was just bursting out of her. Andy captured that. I said in my book that she came through the lens like a fist, and she did.”

Wohl describes Patti Smith’s reaction to Edie as a teenager. She would travel to New York and hang around places she had read that Edie was seen, like The Dom, and took the bus from her home in Southern New Jersey to a Warhol opening at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia at which Edie made a famous appearance that dominated the entire scene. “Patti said, “She was such a strong image that I thought, ‘That’s it,’” Wohl says in the interview. “What’s so interesting to me about Patti’s statement is that she doesn’t speak of Edie as having an image. No, Edie was the image. That’s what was new about Edie, and it was Andy’s doing. What Andy was giving people with Edie was an image of a way of being. And that way of being appealed to Patti Smith and to many other people. There’s a word in French—déclencher. It means ‘to unleash’ or ‘to activate,’ and that’s what Edie and Andy did. Together they unleashed something that society was ready for. Andy was its consciousness and Edie was its face. Andy’s key insight, I think, was to realize that it was movie stars that were the cultural contribution. Movies themselves were incidental. Andy didn’t want Edie to act. He wanted Edie to just be. And that’s the modern form of stardom.”

See what I mean? I didn’t realize when I started reading the interview with Wohl in “Airmail” that I would encounter people I knew in real life, starting with Patti Smith and on through Bob Dylan and Bob Neuwirth (whom Wohl describes as “the love of Edie’s life) and George Plimpton and several other people I would come to know in New York when I worked at the Village Voice. All were famous in their own rights because of what they did with their lives, the art they made, the work they did. But Edie was famous because she was Edie Sedgwick.

Fame is complicated, but real fame isn’t because it is agreed upon by a population and by a culture over time. The extraordinary thing about the life of Edie Sedgwick, so aptly captured by her sister both in her book and the “Airmail” interview, is that despite the fact that Edie Sedgwick existed then and now as flickering images in Warhol films and in black and white photographs taken of a moment in a club or at Warhol’s Factory or at an opening, nearly all of them spontaneous, un-posed – fleeting – her fame isn’t.

She burned like an exploding star, but she didn’t leave a black hole. She left an unforgettable legacy like the image in my memory of the nymph dancing in the street on St. Marks Place, flashes of silver and light and wet reflections in the dark.

I've known women whose existence was marked by an incandensce likened to a pyrotechnic flare. They were a world apart from the rest of us. They were risk takers who seemed to glide through the chaos that followed them as if it were the tail of a comet. They attracted celebrities in the way that bar magnets attract iron filings. They also attract their own special breed of predators who eventually will destroy them. There are no happy endings. The predators frequently skate, but their victims generally do not. The cautionary tale of Little Red Riding Hood ended up in with her in the belly of the Big Bad Wolf. Celebrity itself is a gravitational attractor, which means that the free spirit has no chance whatsoever to escape, because rejecting celebrity is the price of a chance to live a normal existence. The Geoffrey Epsteins of the world are usually more successful than not. That is terribly sad, because accepting normality giving up that transient high that makes people want to risk it all, just to keep it going.

Wohl is Warhol with a couple of letters missing. Edie flashed for an instant, her image seared into pop history before she so soon became repellent due to drug abuse and penury thus not so appealing to predator Andy. Always interesting to read of encounters between civilians and celebrities. Edie's moment was the flash of a camera, the Beatles "moment" was the blast of a solar flare. Andy's fame was / is like a welding torch turned up to 11 in mid-60s then always on, his own "fifteen minutes" will end up being 150 years. So cool to read about casual, ordinary moments of legends at work (Thelonious in this case).