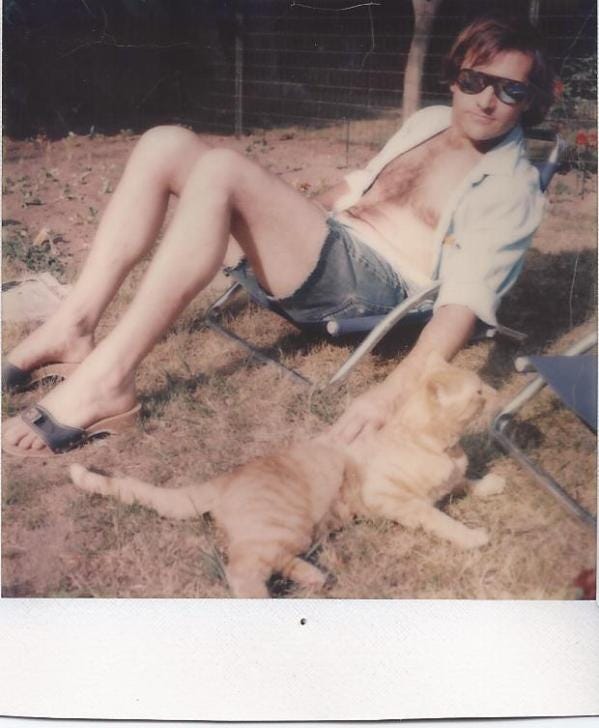

In the loft at 124 West Houston Street.

There is a very small number of relationships you can have with a cat. Ownership isn’t one of them, unless it’s the cat who owns you, which was the case with Orange, the greatest cat who ever allowed me the privilege of living with him.

That’s Orange on my lap in the loft at 124 West Houston Street in the winter of 1975. I had just returned from four months overseas reporting on terrorism for the Village Voice in Israel and Lebanon and spending a couple of weeks in the Netherlands with Frank Serpico that turned into a Voice cover story. I can tell when it was by the Christmas cards displayed on the sliding door between the living space and the bedroom just behind it, which was actually the rest of the loft, all the way to the back wall of windows.

I had gotten Orange on 6th Avenue on Christmas eve two years before. It was snowing sideways, I mean I was leaning into a curtain of the stuff on the street that night. You could just barely make out pedestrians ahead of you on the street, and there was the typical New York City puree of sloppy wet snow and street crud on the ground. I was picking my way through it on my way home from the Pioneer Supermarket on the corner of Bleecker street when I heard a voice call out to me. “Hey, mister! Do you want a kitten?”

I turned to look and saw an old man huddled against the side of a building trying to shelter from the blowing snow. He was holding a cardboard box. I walked over and he held out the box, showing me a single kitten cowering in a corner. “I only got one left. He’s the last one of the litter. I’ll give him to you, free.”

Of course he would. What else do you do with kittens but try to give them away? “I’ll give you some food for him, too,” the old man said, reaching down and picking up a small bag of dry cat food. He held the box and the bag out to me hopefully.

I already had two female cats who had moved into the loft with me from the barge where I had been living on the Hudson River several years before. They could best be described as shy, the kind of cats who lurk under the bed or behind armchairs only emerging to eat and get under the covers when it was bedtime. I didn’t need this kitten, scraggily and soaked to the skin from the snow, but it was Christmas eve. What was I going to do?

I picked him up from the box and tucked him into my bag of groceries, which was already getting wet from the snow and threatening to break open. “Merry Christmas and God bless you,” the old man called out as I headed down Bleecker Street toward McDougal where the lights of the Café Figaro twinkled on the corner.

I managed to make it home without the grocery bag letting go and carried him up the four flights of stairs to the loft. “Look what I got!” I called out to my girlfriend Peggy who already had Christmas dinner going on the stove. I put the bag down and pulled out the kitten and put him down on the floor. He gave his coat a good shake and looked around, quickly spying the bowl of cat food over by the front windows. He marched over there like he had lived in the loft since birth and began chowing down. Curious, the two gray cats came out of hiding and walked over to check him out. He stopped eating just long enough to take his wet front paw and smack each one of them on the nose telling them who was boss. Then he went back to eating.

Peggy laughed at the little guy’s display of mini-macho, and a short time later as Peggy and I sat down to eat our Christmas dinner, he walked up to the table and jumped up on my lap, and from there, climbed up my sweater and laid himself out across the back of my neck. One of the great questions about pets has always been, who lives here – you or me?

That question had apparently been settled once and for all, as it was his habit from that day forth to jump up on a table or chair and onto my shoulders every single time I walked into the loft. We named him after his color as we had the other cats, who we called Little Gray and Big Gray. He had a great coat of ginger fur, but I had had a girlfriend whose name was Ginger when I was much younger, and since that was a girl’s name, we called him Orange. He responded to his name the way a dog would. If he was in the back of the loft and you couldn’t see him, all you had to do was call out “Orange!” and he would come running, straight up onto a table or a kitchen counter and from there to my shoulders. When he got big, he would drape himself behind my neck across my shoulders, with his front legs hanging down one side and his back legs down the other. He never used his claws to stay up there. He seemed to have this unusual confidence that if he got up there, I wouldn’t make any moves that would cause him to fall off. Over the years, I didn’t and he didn’t.

The other dog-like thing Orange did was fetch. One day he found a cap from a Coke bottle somewhere and started batting it and chasing it across the floor. That same day, he carried it in his mouth to where I was sitting and jumped up into my lap and put the cap down on my stomach and then just sat there and looked at me until I picked it up and threw it. He would chase the cap and bat it around for a few moments and then pick it up and carry it back and do it again. When guests came to the loft for drinks or dinner, he would carry the cap right up to them and jump into their laps and put it down and wait until they threw it. Orange became famous in our small circle of friends in the Village as the cat who fetched.

He taught also himself to climb up on top of the three-quarter wall between the living space and the bedroom and leap across a six foot gap onto the bed like a flying squirrel – all four legs extended, flying through the air until he landed on the comforter – and then he would do it again. And again. And again. It took a while to convince him that 3:00 a.m. was not the best time of the day for his flying squirrel act, and he caught on. But he loved it when people would come over to visit who knew his trick, and they would go into the bedroom and slap the top of the bed and wherever he was, Orange would race through the loft and up onto that little secretary you can see behind me in the photo, and from there to the top of the wall from whence he would leap onto the bed to our friends’ great delight.

I took him out to Sag Harbor with me when a few summers later I rented a house where I would write “Dress Gray.” Orange loved it out there, exploring the back and side yards of the house. He would bring his Coke bottle caps outside and carry them to you and get you to throw them across the grass, and he would chase them and bring them back. We didn’t let him out unless we were outside to watch him, and it was a great summer in the little house on High Street until one afternoon when I came back from the beach, Orange wasn’t there. There wasn’t any air conditioning, so nearly every window in the house was open. Apparently he had pushed aside a corner of one of the window screens and gotten out.

We Xeroxed photos of him and plastered the neighborhood, and I went to the police station and the sanitation garage and got the cops and sanitation guys to look for him as they made their rounds. They knew to look for his body as well as an orange cat scampering through one of the neighbor’s yards, but he never turned up, not alive, not dead.

One of the Sag Harbor cops told me that neighborhood around High and Rysam and Franklin Avenue had a lot of old ladies living in the little run-down Saltboxes and “Watchcase factory” houses that had been built around the turn of the century to house the workers at the Bulova Factory on Division Street. One of the old ladies probably took him in, the cop suggested. I chose to believe in his theory. Orange was unafraid of strangers, eager to show off his tricks, one of the friendliest, most out-going cats imaginable. I continued to look for him for the rest of the summer and into the fall, but he never showed up and I never found him. I grew comfortable, finally, with the idea that one of Sag Harbor’s many widows had found herself one of the most amazing cats I had ever encountered.

In the yard on High Street in Sag Harbor.

Orange tabbies are brilliant. Chatham was given to me by his feral mother in Memphis in 1975. He spent three years in Pittsburgh, then fourteen more in Virginia. He owned wherever we lived and always my heart. ♥️

Lucian: I like the photos. They somehow enhance your writing... Makes it real... As for cats? In our concerts at one point near the end Tim turns to me and mentions how it's time to get home to our wives, girlfriends... and cats. The audience cracks up. I don't know why, but I have a hunch cat lovers generally understand this strange communication. Jay Leno once said, "If you think you're rich, famous and powerful, try ordering your cat across the room." It can't be done. That's the thing about cats. They don't give a shit.