Philip Roth cancels himself

Careful how you pick your own biographer. It might turn out that the "perfect" writer is a little too perfect for your own good.

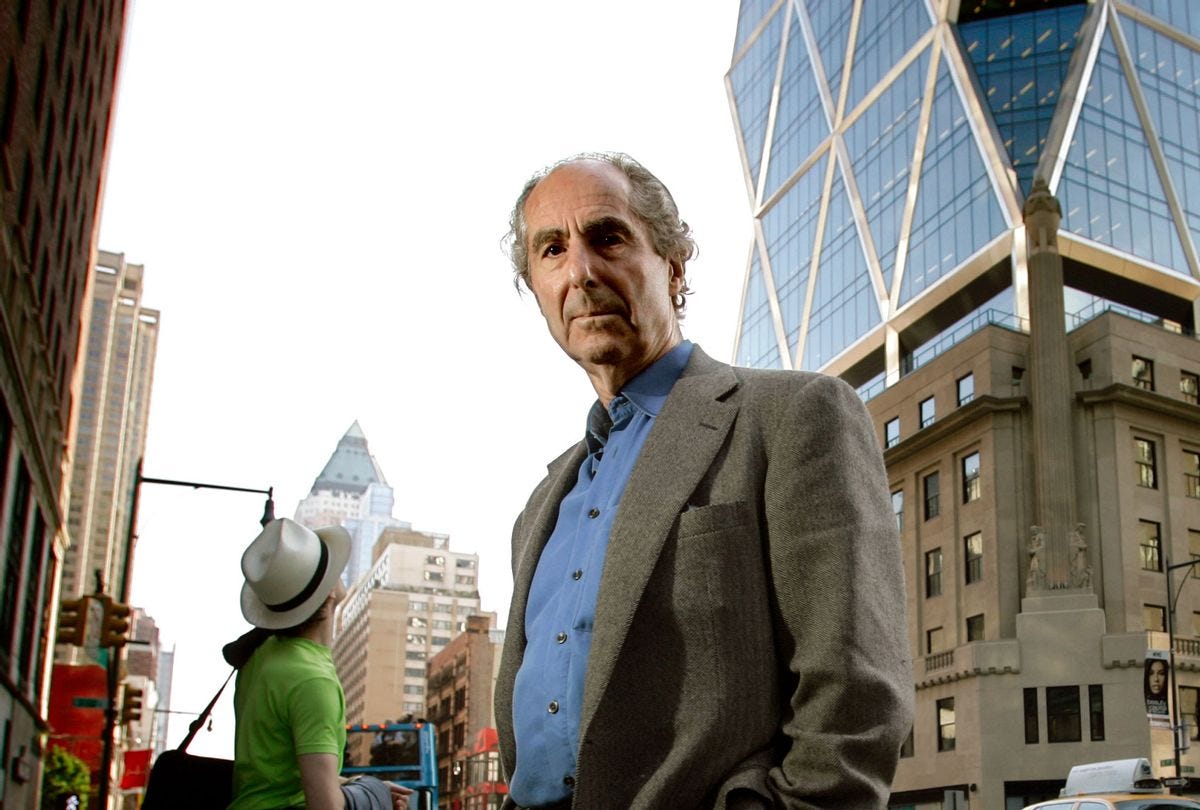

Novelist Philip Roth contemplates his literary legacy

It isn’t often you get to see someone reach out from the grave and do more damage to himself than he managed to do while he was alive, but novelist Philip Roth has apparently succeeded in pulling off this neat trick. On Thursday, publisher W.W. Norton announced it was halting all shipment and promotion of “Philip Roth: The Biography” following allegations that its author, Blake Bailey, had raped two women and sexually “groomed” middle-school girls as a teacher in the 1990s.

Bailey was Roth’s hand-picked biographer. Every review of the book recounts the lengthy and arduous path of Roth’s search for the “perfect” person to write his biography. He began by trying to convince two of his friends and literary soulmates, Judith Thurman and Hermione Lee, who are well known for their literary biographies of Isak Dinesen and Virginia Woolf, respectively. When his entreaties didn’t work out, he turned to another friend, Ross Miller, an English professor at the University of Connecticut. Miller signed a contract to write a Roth biography in 2004, but it didn’t take long for the relationship between author and subject to go sour. Roth apparently thought Miller was concentrating too much on the famous author’s notoriously difficult relationships with his two ex-wives and literally fired him by fax, declaring that he was “too fucking angry” to talk to his biographer. Miller, who had never written a biography before but who was already deep into interviews with Roth’s friends and acquaintances, told friends that Roth was “surrounded by sycophants” and walked away from the project.

After briefly considering James Atlas, author of a well-received biography of Saul Bellow, Roth settled on Bailey, who had written well-received biographies of John Cheever and Richard Yates. Bailey proved far more simpatico to the prickly Roth, who was famously obsessed with both his literary reputation and also with his reputation as what we might call a “ladies’ man.”

The two “ladies” Roth was most obsessed with were his wives, Margaret Martinson, a former waitress from Chicago, and Claire Bloom, the English actress. His marriages to both women were, shall we say, tempestuous. Martinson conned him into marrying her by faking a pregnancy, buying urine from a pregnant woman, and then faking an abortion — this alongside having had two actual abortions after becoming pregnant by Roth, one before the one she faked, and one demanded by Roth during their marriage. He did wring some use out of his marriage to Martinson by basing the two main female characters in “Letting Go” and “When She Was Good” on her, and he eventually made use of what he and Bailey both refer to as “the urine fraud” by having the main female character in “My Life as a Man” perpetrate the same marital treachery.

Generally, Roth’s interest in casting his ex-wives as betrayers was in “winning” wars against them that divorce could never satisfy. Bailey provides help to Roth by transforming both women into literary cannon fodder. In Bailey’s book, women in general, but the two former wives in particular, are depicted as harridans who continually make unreasonable demands on the great writer’s time. Bailey seems to be entirely in Roth’s corner when he describes the way women in his life constantly nagged him to pick up something at the grocery store or take them shopping or drop them off at the hairdressers. It seems that when women weren’t making themselves available for Roth’s horizontal gymnastics, they were of little use to him.

Roth’s relationship with actress Claire Bloom was, to put it mildly, peculiar. At one point, Bloom went to visit Roth in a psychiatric facility he had checked himself into to be treated for depression — from which he suffered throughout his life — only to end up checking herself into the same facility. But Bailey most tellingly takes Roth’s side in his description of the novelist’s relationship, if it could be called that, with Bloom’s teenage daughter, Anna. Roth is described as constantly complaining about the young girl’s weight, telling friends how fat she is. Bailey describes him as so jealous of Bloom’s relationship with her daughter that he eventually demands, in writing, that Bloom’s daughter had to go or he would. Bloom gave in, and later described Roth’s demands in a distinctly unflattering light in her own memoir, “Leaving the Doll’s House.”

Bailey tells of Roth at one point making an aggressive sexual pass at one of Anna’s friends. When rejected, he makes insulting comments to her every time she visits Anna. Bailey describes Roth defending his behavior, quoting him saying, “What’s the point of having a pretty girl in the house if you don’t fuck her?” Bailey describes this remark as Roth’s “impulse to mock a certain kind of bourgeois piety,” which — given this week’s news of Bailey’s alleged “grooming” of teenage girls for sex, and his alleged rapes — has become an aside that now appears in an entirely new light. “Bourgeois piety?” Whose bourgeois piety could he be referring to, pray tell?

Bailey’s biography of Roth, who made no secret of his sexual obsessions and did little to conceal the numerous affairs he had with women he was not married to during his lifetime, appears now as a telling document of obsessions he obviously shared with his subject. Bailey takes Roth’s side throughout the book in his many contretemps, large and small, with the women in his life. Roth is described as constantly having to put up with women’s pettiness and annoying demands on his time. The women are, Bailey seems to agree, a singular threat to the great man’s genius, and when Roth is attacked by Bloom in her memoir, a threat to his literary career as well. It’s surprising, finally, that Bailey doesn’t blame Roth’s failure to receive the Nobel Prize on Claire Bloom or his extensive list of lovers. Such is the burden of greatness, Bailey seems to be saying on behalf of his subject.

Given the events of the last 48 hours in the life of Blake Bailey, he may well rue the day he ever agreed to write the biography of perhaps the most sex-obsessed man in American letters. And from the grave, Philip Roth must be ruing that he picked Bailey as the man to whom he would entrust his literary reputation. A canceled book, even one as glowingly complimentary as Bailey’s biography of Roth, will be difficult to check out of a college library if it’s not there.

The proverbial chickens have come home to the proverbial roost in the lit-world. Bailey quotes Roth as complaining that things have turned so puritanical that if you sleep with young women who are your students these days, “you go to feminist prison.”

You’re going to look good in your orange feminist prison jumpsuit, Blake my boy. It’s too bad Philip Roth left this mortal coil before his biography was published. They would have made great cellmates.

Lately, I've been thinking about the great artist/terrible person conundrum, although I alluded to it some years ago here: https://selfabsorbedboomer.blogspot.com/2008/05/so-just-what-is-art-anyway.html

I've not read much of Philip Roth's works. I read Portnoy's Complaint not long after it was published, and must confess that, as a horny early twentysomething, I took some pleasure in its misogyny. I think if I read it now I wouldn't enjoy it. Later in life I read The Ghost Writer, in which the protagonist, Roth's literary alter ego Zuckerman, becomes obsessed with a young woman he is convinced is really Anne Frank, who somehow managed to survive. It left me feeling vaguely uneasy.

For a long time I've been troubled by the overt antisemitism expressed in a few of T.S. Eliot's poems, and by F. Scott Fitzgerald at the conclusion of The Great Gatsby. There are other hard cases, for example, the fascism of Ezra Pound and of William Butler Yeats. I don't think these writers should be "cancelled." I think the hysteria over "cancel culture," as evinced by the recent brouhaha over the withdrawal of four Dr. Seuss books from publication, is silly. I'm planning to write more on this subject soon.

Let’s not forget, though, that there are plenty of young women students who are eager for sexual relationships with their professors. I’ve supported feminist causes throughout my adult life, but I can’t agree with a certain type of bitter feminist Puritanism that assumes ALL such relationships are somehow coerced by the male professors, and that the young women are always helpless victims.