I’m going to tell you something that you won’t hear from many writers. I’m going to tell you how you write a story and what the process is, but mostly, I’m going to let you in on what it feels like.

What made me think about it was re-reading the Tango Palace story I posted on Christmas eve. It’s a story I have a very strong memory of, because how many times do you spend your Christmas eve on Times Square in what they used to call a dime-a-dance parlor talking with one of the “hostesses?”

The whole thing came back to me like it happened yesterday. It was 1970. I had been living in New York and working full time for the Village Voice since July. It was a really cold night. I’m pretty sure there was snow on the ground. For some reason, I had been up to Times Square recently and had walked past the Tango Palace and was curious about what the place was like. It was on 48th and Broadway in a strip that included the Warner, an old movie theater, pizza joints, an Automat, a little storefront that just sold ties called Tie City – the typical array of Times Square businesses of the time. Everything was run-down looking with lightbulbs missing in the marquees, neon lights that blinked not because they were supposed to, but because they were on their last legs.

I know exactly why I wanted to go there on Christmas eve and write about it: There was practically no way it wouldn’t work. The Tango Palace was on its last legs and would close a few years later, a part of New York City that was going away. But I wasn’t looking to capture disappearing local color. Going there would be slumming, guaranteed pathos drenched in faded glamor and glitter. In fact, I remember when I walked in and saw the disco ball spinning forlornly above the empty, scuffed dancefloor, I knew I had hit the jackpot.

There are lots of different kinds of stories in journalism, but what separates two of the major ones involves whether or not you identify yourself as a reporter. If you cover a City Hall press conference, it’s a given. If you go out to write about a rock and roll band, or a dance company, of course you’ll be seen as a reporter for a publication like the Voice or Rolling Stone – that’s the way you get to interview the rock star or the dancer. But if you’re out on the street and something happens right in front of you, the way it did when I was walking from my loft to a bar on Christopher Street and ran straight into the riot at the Stonewall Inn, introducing yourself as a reporter wouldn’t be the best idea. It’s usually better to let the event happen and catch snatches of dialogue in the crowd and watch the action from the sidelines.

But there’s another kind of story when it’s often better not to identify yourself. I attended political fund raisers and campaign events, most recently a Trump rally in 2016 here on Long Island, without using press credentials or IDing myself to people as I spoke to them. Sometimes it’s necessary: often private fund raisers are off-limits to the press, and the Trump people would have caged me inside a press enclosure away from the crowd if I said I was a reporter. They wouldn’t have let me in at all if I had said I was from the Voice, because the paper had published numerous investigative stories on Trump over the years that weren’t exactly endearing.

The Tango Palace wasn’t a public event like a political rally, or a private one like a fundraiser in a big donor’s Fifth Avenue penthouse. It was a public place in the sense that if you paid your money at the door, they let you in. But the “public” aspect broke down when it came to choosing one of the hostesses and then interviewing her by chatting like any other taxi-dance customer might. At that point, even though I had no plans to identify her by name, I was invading her privacy, but I knew if I paid my $10 and told her I was a reporter for the Voice and I wanted to interview her, I would have gotten nothing. She might have just walked away, or more likely given monosyllabic answers to any questions I asked, and the whole “chatting” thing would have been right out the window.

I remember talking with her over the 30 minutes my $10 bought me. She asked me some questions, like if I was a musician, and I told her I had been in the Army and recently moved to the city, which was true as far as it went. As we chatted, I picked up a smattering of details about her – that she lived in Brooklyn with her mother, she’d been working at the Tango Palace for a couple of years and wanted to move along.

But I was looking for something good, some detail about her life in general, or her years at the Tango Palace, that would work for the story. I wasn’t chatting with her, I was interviewing her without telling her so. I remember running a mental clock, and as we got closer to the end of my half-hour, I got a little desperate. I thought maybe I’d have to put up ten bucks for another half hour when I casually asked her what last Christmas had been like, and she told me about the one customer she’d had that night, how he had “ended up buying me a color TV. A big color TV.”

As the words “color TV” came out of her mouth, I knew I had struck journalism gold. It was the kind of moment you prayed for as a writer, to have what amounted to the theme of your story delivered to you on a platter. And you have to realize what a color TV meant in 1970. It was something you coveted, something you dreamt of. They were expensive enough that I didn’t have one. You could get a good used car for what a color TV cost. Getting a color TV was a passage from one level of the middle class to a higher one, where people would come over to your house to watch a game or a popular show just because you had one.

It was after she told me about her color TV that she said she was saving her money to open her own hairdressing salon. Outside, on Broadway, I had seen a sign advertising a “School of Hair Design” on the second floor of a nearby building. There were billboards advertising color TV’s by Sylvania and Phillips and other big companies all down Times Square. It was a place that shoved 40-foot tall dreams at you lit by a thousand light bulbs, and yet reality was all around you sizzling on the grill at Tad’s Steakhouse or coming out of an oven at a two-dollar pizza joint or ready to go around your neck at Tie City.

Striking journalism gold happened again, but not frequently. Years later I was writing a story about Columbia Pictures, interviewing a wealthy investment banker who owned a controlling interest in the company. I was trying to understand why he had not fired an executive of the company in Hollywood who had embezzled money from several movie stars, but he wouldn’t come clean. I pushed and pushed and finally he got so angry, he grabbed me by the arm and pulled me over to a glass wall between his office and his company’s trading floor. He pointed through the glass and asked me, “Do you know what that is out there?” I played dumb and said, no I didn’t. “That’s a trading floor. We do business with crooks and thieves and scoundrels every day out there. That’s the way this company was built. That’s the way this country was built, and don’t you forget it.”

I scribbled his lines into my notebook and closed it and said thank you very much and excused myself and left. I had the quote I’d been waiting for. The details of what had happened with the executive who stole the money hardly mattered, because I had squeezed the truth out of him. The investment banker knew who I was, he knew I was writing a story for the Times Sunday Magazine, so there was no subterfuge about my identity. But I knew from reporting I’d already done on the story that he was the kind of guy who would explode if I pressed him long enough and hard enough and that he finally he would cough up the truth.

I remember walking out of the Tango Palace with my story already written in my head. It was ideal, sitting right at the intersection of happy and sad: I had scavenged the tattered boulevard of broken dreams and found one that had come true on Christmas eve. I wrote the story the minute I got back to the apartment, and it ran in that week’s paper.

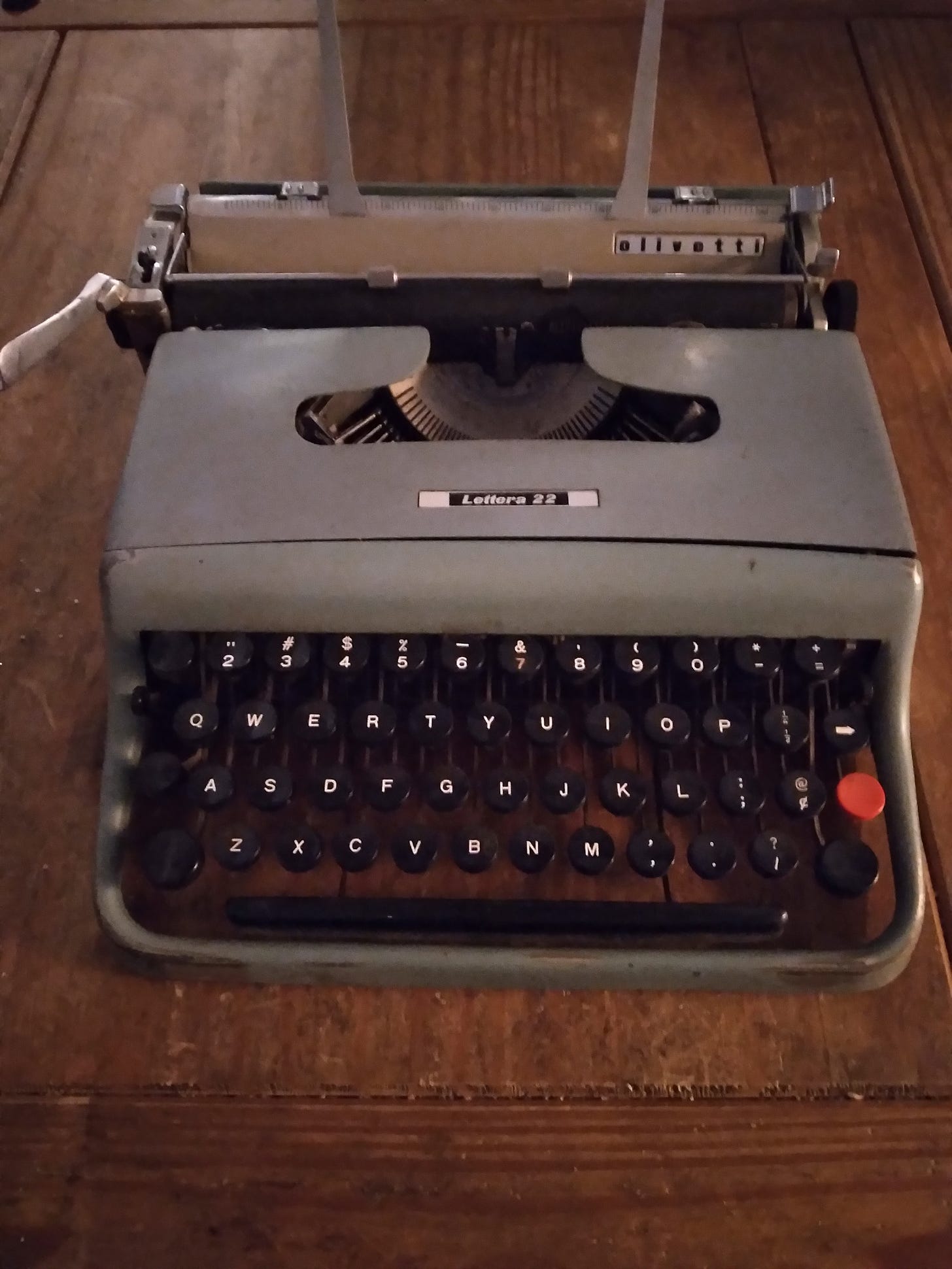

That’s what writing the Tango Palace story felt like. I sat there and pulled the last page out of the typewriter with the guilt that comes from a truth about journalism I live with even 50 years later: I exploited someone’s life for $80 a week and a hundred compliments from friends and fellow writers at the Lion’s Head, and then I went out and did the same thing all over again for next week’s paper.

This might be my most favorite of your columns since the one about being a Jefferson descendant. It touches something I've come to call "feminist journalism," though it isn't exclusive to feminists and indeed predates the modern feminist movement. The realization that "objectivity" doesn't exist. That journalism is ipso facto exploitation -- journalists come into other people's lives and take those people's truths out of context for an audience that usually doesn't include them -- but that sometimes justice, humanity, illumination, truth, any or all of those things, comes out of it. Maybe being able to write the story of how you got the story is what it's really all about. The heart of it anyway. This is a keeper. Thank you.

Lucian, yours is the one email in my in-box that I never delete before reading. Your essays always evoke an emotional response and I can almost smell the places you describe. In this era of stale “journalism”, you are a breath of pure oxygen.