(This story first appeared in the May 6, 1971 Village Voice.)

Out on the street, a group of black clad tough-looking longhairs who called themselves the Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers were distributing a handbill. It was a bitterly cold Friday in late December of 1968, and few people paused to take the hastily prepared statement describing a brief seizure of the Fillmore the night before and calling for a renewed struggle for a “free Fillmore” over the weekend. The Fillmore East, or so believed the UAW/MFs, belonged to the “people,” and it was up to the “community” to take what was rightfully theirs.

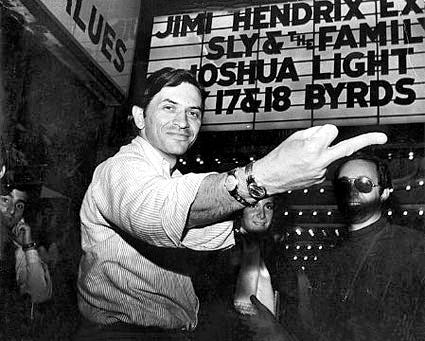

Inside sat an unshaven and unsmiling Bill Graham, who owned the place. He had been lashed across the face by an unfriendly biker during the previous evening’s confrontation while the MC5 was playing, and his swollen and scarred nose glowed red as he spoke in the colorful language he was given to use during such times. “Those crummy fuckers. Those snotnose punks. Gimme that sheet. Lemme see what they’re sniveling about now.”

He came from the Bronx, he said. As a kid, he was a member of a gang known as the Pirates. The distinctive green and yellow of the Fillmore jerseys worn by the staff is a hangover from his gang’s old colors, said Graham, reading the UAW/MF handbill. On the streets of the Bronx, he ran across the likes of the group parading around outside more than once. It seems Graham already had ideas about how to deal with them. “They come in here last night yelling about me ripping off the community. Those rotten pieces of shit. They all want something for nothing. One of ‘em says last night, ‘Hey, Graham, why’s your hair getting so long, huh? You trying to get hip?” So I told them, I don’t give a half-assed fuck about my hair. I just haven’t had time to get it cut, that’s all.”

He stopped and ran a thick hand through the aforementioned hair. The phone rang. It was Mike Bloomfield, the guitarist who was then playing highly touted “Supersessions” at the Fillmore with organist Al Kooper. “Where are you?” Graham barked. “You stupid fucker. I told you to be here this afternoon. Don’t give me this ‘I’m snowed in’ shit. I don’t give a flying fuck if Gravenites is gonna be here. Your name is on the program, not his. Listen, you better be on that stage tonight, or it’s your ass, and I don’t care if you have to charter a fucking plane to do it.”

Slam. Smile. “Now where were we. Ah, yes, those scumbag fucks outside. I’m so sick and fucking tired of listening to that ‘rip off the community’ bullshit. I told those pieces of shit, you get the musicians, and you get the equipment, and you pay my stage people, and I’ll let you have this place on Wednesday. Those crummy punks. They want it all done for them. Well, let me tell you, I won’t give them nothing. For all I care, this community can fucking shrivel up and die if they continue to let themselves be represented by that bunch of cheap-ass chicken-shit punks.” The phone rang again. More barking. More threats. Slam. Silence. Bill Graham. Pig capitalist Bill Graham. The man everyone hates. Everyone.

It's been three years since the Fillmore East opened. Two years since the AUW/MFs last showed their faces on the Lower East Side. A year and a half since anyone has talked to Graham about the “community.” A little less than a year since the deaths of two of the Fillmore’s biggest headliners, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. Six months since anyone at the Fillmore can remember the trouble with kids bad-tripping on acid. Now they’re eating reds and putting a fuzzy, angry edge on things with cheap wine. Many of them pass out in their seats during the show. And maybe that, more than anything else, explains why Bill Graham announced last Thursday that on June 27, 1971, the Fillmore East will close with its San Francisco counterpart following.

“The scene has changed,” Graham said in a prepared statement for the daily press, “and in the long run, we are all to one degree or another at fault. All that I know is that what exists now does not seem to be a logical, creative extension of the beginning.”

It’s hard to imagine Bill Graham confused, leading a statement to the press with an implied shrug and “all I know is….” because he was there at the beginning and has led the way ever since. Graham has had few uncertain moments during the years since Ken Kesey’s Trips Festivals in San Francisco, the first time that music and light shows and the burgeoning psychedelic scene were brought together in a public place. There was no doubt in his mind that such a thing could be reproduced, and it wasn’t long after those first festivals that Graham quit his job as the manager of the struggling San Francisco Mime Troupe and began a new career as the greatest impresario of live rock music this country has seen. His business sense, a finely tuned and hard-edged version of the instincts he had picked up on the streets as a kid, told him that the Fillmore could be the start of something big. It was. Graham has single-handedly produced more live rock music for more people in the years since he opened the first of the two Fillmores than any other man alive. And he’s racked up that record with not just the most, but the best production and atmosphere in the business, bar none.

He's a pro. At his best, Graham has always reminded me of an Army first sergeant. He is loud and abrasive, and he cusses a lot; in his own words, he’s a “dictator.” To him, there is no substitute for the job being done right the first time, no excuses accepted. “If I want that spotlight right there now,” he told me with a snap of his fingers last week, “then it had better be there. Not one second from now, not one second before, but now. That’s the way it’s got to be, and man when it happens, there’s nothing more beautiful. My fondest memories of this place will be of the people who worked here, the guys who got that spot right every time. This is no commercial for me, man. I’m a hard man to work for, but my people have done it, and they’ve done it in spades. When it works, it’s beautiful, man, and it’s been beautiful around here for a long time.”

I pity the people who try to recreate the Fillmore when Bill Graham and his crew leave, because that madman, that lovely, lovely madman has gotten the job done, and he’s left one hell of a lot to live up to.

I think the time has come to heap some praise on old dirty-button-down-shirt-wearing Bill Graham. Since the doors of his auditorium on 2nd Avenue on the Lower East Side opened on March 8, 1968 (with Janis Joplin making her second major appearance), more than two million people have filed through to get their money’s worth, and then some. The people who bitch about Graham and the Fillmore, the ones who have marked him “the anti-Christ of the underground,” as he put it, have forgotten some important facts.

Graham has sponsored literally hundreds of benefits at both Fillmores for causes which have run from dying radical newspapers to VD to peace in Southeast Asia. “Show me a cause,” Graham once said to me a few years ago, “and tell me why I should be for it, and if I’m with you, I’ll do it.” Not only Bill Graham has been there with his time and energy, however. His staffers have worked benefit nights for free more often than not, a fact that is little known and even less appreciated. And Fillmore benefits have been more important than many people realize. The anti-war movement alone must be into the Fillmores on both coasts for thousands.

Who could forget the free concerts, given chiefly by the Grateful Dead and other San Francisco bands which have been friendly with Graham over the years? The stories behind the concerts are rife with the kind of secrets old anti-Christ has shared with few. One concert given by the Dead in Central Park is a good example. To get the city to agree to the use of the bandshell, Graham had to supply the Parks Department with several hundred wire trash baskets due to a shortage claimed by the city. They remained in the park when the Dead were long gone, a rather expensive donation to the city for that “free” concert. For that single concert, Graham gathered 200 kids off the streets of the Lower East Side to serve as his clean-up detail. They cleaned the park from 59th Street to Bethesda Fountain twice on the day of the concert. Graham gave them subway fare, Fillmore t-shirts, seats close to the stage for the concert, and breakfast and a midnight supper at Ratner’s deli. They worked from 5 a.m. until dark, and old capitalist pig Graham was right there with them the whole time.

Then there were things the Fillmore did for people in the business. Thanksgiving dinners in New York at the Fillmore East (I ate at the Fillmore East with the Dead and the Jefferson Airplane one year), Christmas dinners in San Francisco at the Fillmore West, and New Year’s Eve celebrations in both places. Ask the musicians about playing the Fillmore sometime. Ask Paul Butterfield, who never played there that he didn’t find his favorite beer and pizza waiting in the dressing room between shows. Or ask Al Kooper, for whom Graham rented a harpsichord at $200 a night so he could plink out one song on it each show. It’s the little things that count, they’ll tell you, and the Fillmore never missed even once.

Okay, okay, maybe Graham isn’t so perfect. And maybe I’m a little fonder of him than most because of my general affection for people who do a job well with little pomp and no circumstance. Professional. Austere. That’s Graham. I admit it. I like that, and because I like it, because I see a place on the scene for a guy like Graham, this piece is a tribute, an appreciation of the man who founded the production of live rock and roll music as we know it today.

Alas, the scene, as Graham said Thursday, has changed. Prices are up; rock acts that used to be a band are now huge corporations; agents are promoting not just one group but a “package” that more often than not demands booking a mandatory third-billed act along with the headliner, or no deal. Audiences have changed from peace-and-love masses of psychedelic boppers to angry mobs of hungry consumers that scream “more” as a demand, not a plea. And finally, the drug scene has become a frightening monster – bad trips may be few at the Fillmore these days, but fights are breaking out for the first time in the history of the place. The scene on both sides of the stage is big and powerful and dangerous. Pretty soon, there won’t be britches big enough to fit the thing Bill Graham has wrought. When that happens, he won’t be around to yell and cuss and with black eyes and gritted teeth.

He'll be missed. The promoters who have shoved their acts into massive caverns like Madison Square Garden, and the musicians who have twanged all the way to the bank inside those hollow environs, will lament it with no Fillmore to fall back on when the 20,000 seats just don’t sell out anymore. And the consumers, that demanding lot with a well-honed taste for their money’s worth, may has well hang it up. He’s been an angel, and he’s been an asshole, but the rules that Bill Graham set down to play the wild rock and roll game have been as steady and reliable as clockwork. You play the Fillmore alone, and you play for one half the gross, no more, no less. You buy a ticket and listen to the music, and you listen to the best, no more, no less. It hasn’t been that way anywhere else but the Fillmore, and come this summer, it won’t be that way ever again. It’s the end of an era, folks, and I, for one, am damn sad to sad to see it go.

Wolfgang’s Vault is sort of his legacy company. The story is that the heirs, cousins I believe, fought over the estate for years, the main asset was a building in downtown San Francisco. They finally settled in maybe 2005? Anyway none of them ever went inside and they sold it to condo developers for $5 million. The buyers went inside and found he saved posters and tickets and handbills (the tickets and handbills are small replicas of the posters) from every show and realized they had something worth hundreds of millions so they opened up a website and starting selling the posters and tickets. He commissioned the art from the most famous and prolific counterculture artists! When the buyers went into the basement they found a locked bank vault, inside were films and recordings of every show! Which once the get all the rights resolved, and they will, is probably worth a billion or so…

George Harrison, in (Beatles Anthology) spoke of how he wanted to go to San Francisco and groove with a new civilization in the making. It wasn't pretty. Thousands of stoned kids crapping in the alleys and thousands more sleeping where ever and hundreds facing disaster when local hospitals shut their doors to the crazy's and the damaged. In New York City the Fillmore was a magnet and it attracted a lot of damaged kids. It is unfair to blame Bill Graham for the worst of it. He inspired a generation of musicians and boys who grew up to be producers and promoters. No one really understood the magnitude of the Hippie Era until it was over.

Lucian Have you any idea the value of your writings, especially from the 1970's? Your stories are authentic history and they affect even the hardcore cynics. Thank you sir.