Saturday Reprise: Words and sentences and me

Writing came naturally to me after thousands of practice runs

I first posted this in August of 2001. It’s good to look back at where you came from and who helped you get here.

The words you’re reading right now don’t belong to me.

What does belong to me is this sentence, and the one above, and every one I’ll write today and every other one I’ve written in my lifetime.

Writers use words the way a carpenter uses nails, because without nails there wouldn’t be a wall or a floor or a window frame or anything else the carpenter builds. Same with writers: without words, the writer couldn’t build a book or a screenplay or a short story or a poem or a column.

But words don’t turn into the walls or windows or floors of a piece without being nailed together into sentences. I think of sentences as what I use to build what I write. You can find words in a dictionary or a thesaurus or a rhyming dictionary or even an old fashioned phone book, but you can’t find sentences in any of those places. Sentences are what I do.

For some mysterious reason, I’ve never been able to do word games like crossword puzzles or Scrabble or the word games they play with callers on NPR every weekend. When I say I can’t do them, I mean it. I look at the clues in a crossword puzzle, but unless they nearly spell out the word, I don’t get it. I think it must be because words don’t gain meaning for me until they’re used, and what they’re used in is sentences.

I think I’ve told this story elsewhere, but as you will see, it’s worth telling again. I learned to write sentences, and to love them, from my 7th grade English teacher at George S. Patton Jr. Junior High School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1959 and 1960, Mr. Lockhardt. To say that he was one of a kind doesn’t come close to doing him justice. He had a tangle of curls on the top of his head that somehow managed to look neither messy nor attended to and came to school every day in a long sleeved white shirt and tie, and he took his place behind his desk in a classroom, and he taught 7th graders how to write sentences for almost 50 years, the last ten or so as a substitute teacher because he didn’t want to quit after he had reached mandatory retirement age.

Mr. Lockhardt had a deceptively simple teaching method. He began each day by going to the blackboard and writing a sentence. I recall that he started with the simple declarative sentence: Jim threw a ball. Then he diagrammed the sentence, showing the noun, verb, and object and told us to take out our notebooks and write 20 declarative sentences.

When the sentences were simple, he sat down at his desk and waited until we were finished and then he took our notebook pages and graded them right there in front of us. When he was finished, he handed them back to us. As the sentences became more complex, we would begin writing them in the classroom and finish as homework and hand them in the next day. I know that he was teaching us grammar and usage, and as the year wore on, we would be required to write sentences with prepositional phrases, like The boy caught the bus on time. And then we were required to write with a prepositional phrase that modified nouns and verbs and prepositional phrases that act as nouns and verbs and eventually prepositional phrases that act as adjectives and adverbs.

And onward through the sticky wicket that is the English language we went.

But here’s the thing: Mr. Lockhardt never required us to memorize the names of the rules we were following. I had to look up “pluperfect tense” to remind myself what it is, and I stole the example of the prepositional phrase above from a website called “PrepScholar” that is supposed to get you ready to take the SAT’s or ACT’s. All Mr. Lockhardt wanted us to learn was how to write those sentences, not remember the grammatical terms of what they were. To this day, I couldn’t tell you what the future perfect verb tense is. I had to look it up, so here’s an example I found on another grammar website: The parade will have ended by the time Chester gets out of bed, “will have ended” being the future perfect tense of the verb describing the “action” of the parade.

Well, let me tell you: the more complicated the sentences got, the more I loved puzzling them out. The other thing Mr. Lockhardt insisted was that the sentences say something, that they make sense. It wasn’t good enough to write “The thing will have ended…” You had to use the pluperfect tense in a way that you could understand what the sentence was saying, so “the parade” was okay, as was “the game,” and so on. It made the sentences that much harder to require them to actually say something, rather than just slapping whatever it was we were learning to use in between some random words.

The other thing Mr. Lockhardt didn’t require you to learn was to diagram the sentences. He just wanted to see that you could write using the particular grammatic construction properly. But as you will see by the following, being able to diagram sentences I wrote became more and more necessary as the year wore on.

That’s because the first thing Mr. Lockhardt did every day was hand out the homework we had done from two days ago complete with our grades, so we were graded every single day. If you got a sentence wrong, he might mark it with some red ink indicating what you had done wrong. If the sentence was really wrong, he would just draw a red line through it, and if you got a lot of sentences wrong, you would be required to do the homework over again until you got a passing grade.

Once we got our papers, he gave us a few moments to check our grades and if there were mistakes, see what we had gotten wrong. If you thought that he had marked something in a sentence as a mistake for a wrong reason, you could raise your hand and challenge his grading of your sentence. If you were right, and the mistake he’d made in grading you was clearly wrong, he would up your grade automatically to an “A”. But if your challenge didn’t hold up, he gave you an “F”. It was all or nothing, and that’s where having to learn to diagram my sentences came in, because when he had gotten something wrong and continued to dispute it, you were allowed to go to the board and write the offending sentence and diagram it to show you had the grammatic construction right.

I didn’t get many sentences wrong. I got used to getting an “A” every day, so when I thought Mr. Lockhardt had made a mistake, I challenged it. Sometimes I won the challenge and got my “A,” but when I didn’t, Mr. Lockhardt would reach into the bottom drawer of his desk and pull out one of those maddeningly small gym towels and wad it up and throw it and hit me in the chest.

“The crying towel for you, Mr. Truscott!” he would call out loudly. “F.”

As you can imagine, I worked hard on that list of sentences every night, and glory be! I discovered over the coming years that I had learned to write.

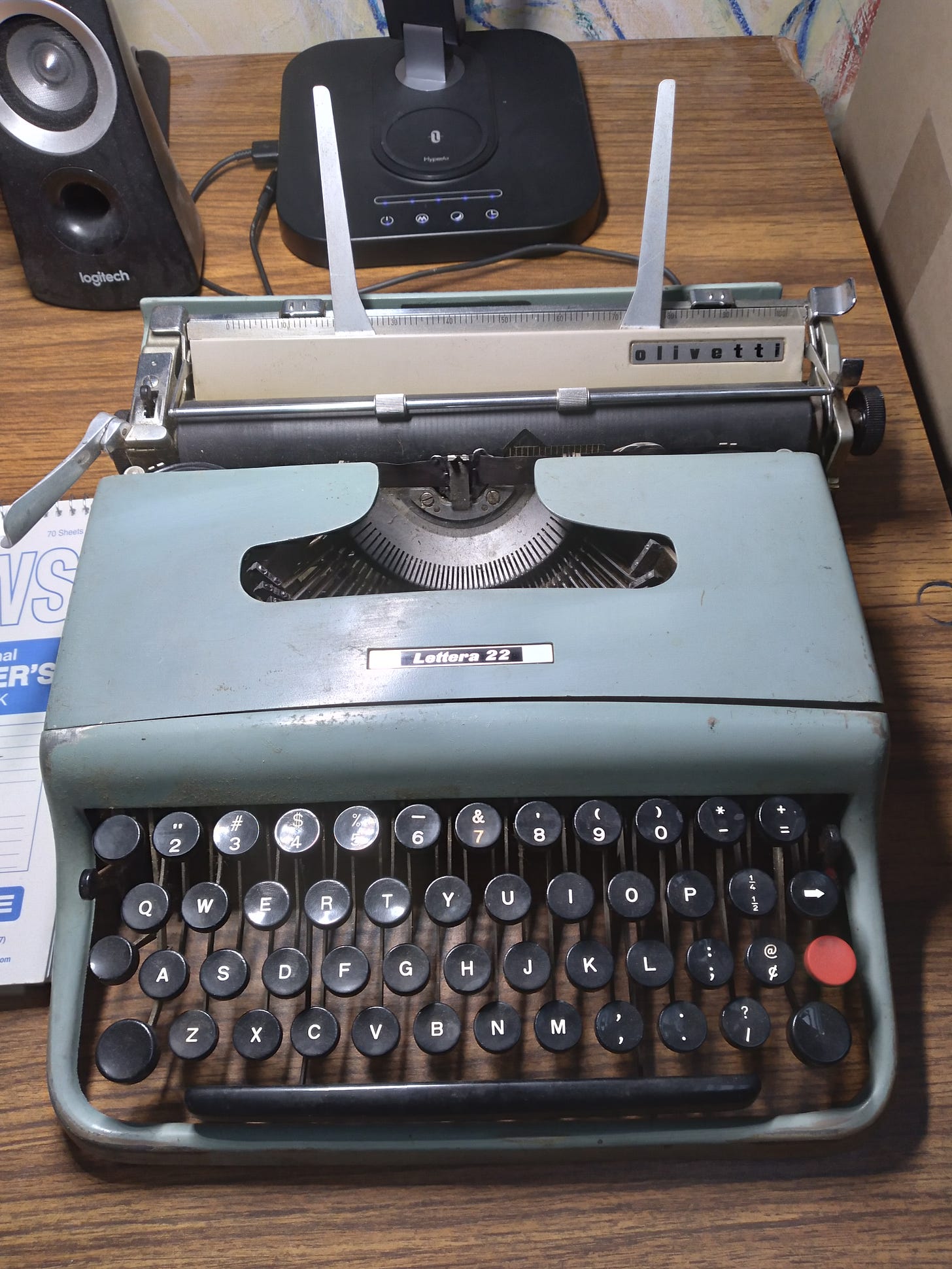

As it happened, being an Army brat, I did a lot of writing other than English grammar assignments. We moved practically every year, so I was always writing letters to friends…including girlfriends…I had left behind at the last duty station. I ended up going to three high schools in three states in three years. I wrote many, many letters, and after I learned to type Sophomore year, I typed every one of them.

My mother found some of the letters I wrote home when I got to West Point and showed them to me. I was amazed. They weren’t “how are you, I’m fine” or “I hate this place” or even “I can’t wait for Christmas,” although one of those notions might sneak into letters every once in a while. I wrote letters that said something, that told stories about what had happened on a particularly difficult field exercise, or about the excitement of going to see Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot in New York City (rather than watching West Point play basketball in the NIT tournament, which is what I was supposed to be doing.) I found one letter that told of walking out of the Five Spot at midnight one time and looking down the street and watching Andy Warhol and Gerard Malanga and Edie Sedgewick as they exited The Dom, where the Velvet Underground (managed at that time by Warhol) was playing with a lightshow called “The Plastic Exploding Inevitable.” I can still see the image I captured of Edie Sedgewick, in a sparkling silver mini-dress and heels with her platinum hair, twirling down the middle of St. Marks Place with her hands above her head like a ballerina singing the chorus of The Velvet’s “Run Run Run:”

You gotta run, run, run, run, run

Take a drag or two

Run, run, run, run, run

Gypsy Death and you

Tell you whatcha do

All my trips to the city and a subscription to The Village Voice led to me writing letters to the editor of the Voice, which they were happy to publish with the byline, Lucian K. Truscott IV, West Point. In 1968, I spent my Christmas leave in the city at a girlfriend’s apartment in the East Village, and on Christmas day I walked over to The Dom, which had just become the Electric Circus, to see a Christmas “be in” by Wavy Gravy and the Hog Farm. I thought it a bogus exercise in hippie fascism, with Wavy ordering all these stoned kids around and yelling at them to “have fun” like he was a stoned drill sergeant. So, I sat down and wrote another letter to the editor of the Voice and shoved it under the door on Christopher Street that night. Amazingly, on the following Wednesday, the Voice ran my letter as an article on the front page with the title, “Pocketful of love but no readmission,” and sent me a check at West Point for $80, and just like that, I was a published writer.

In the summer of 1974, I was driving across the country writing stories for the Voice and when I saw that I was approaching Kansas City, I took a turn and drove up to Leavenworth with the mission of thanking Mr. Lockhardt for teaching me how to write sentences. By that time, I had been published for 5 years.

I found him living in a little garage “back-house,” and as I walked up, I could see him through the screen door lying on a sofa with a big fluffy cat on his stomach watching a baseball game on a small black and white TV. I remember that when I knocked on the door it was hung loosely, so each time I knocked it made two sounds: the knock, and the sound of the screen door banging against the door jamb, thunk-thunk…thunk-thunk. Mr. Lockhardt had the volume on the TV up loud, so it took a few knocks, but finally he turned his head and called out, “Who’s there?”

I replied through the screen, “It’s me, Mr. Lockhardt, Lucian Truscott. I’ve come to thank you for teaching me how to write.”

As he sat up on the sofa and moved the cat off his stomach to the floor, he smiled widely and said, “Well, it’s about goddamned time, Lucian.”

In his his small place were piles of back issues of the Voice with my stories on the front page and copies of magazines like Esquire with articles I’d written. We sat for a few hours and talked about the days when I was in his 7th grade English class, and he asked me about stuff I’d written, and of course, he remembered a few grammatical errors in my sentences. I remember telling him that after I took his class, I never learned another thing in junior high, high school or West Point about writing. I told him when I sat down to write, I never thought about the construction of my sentences or whether they were correct or not, because I knew nearly every one of them was. All I had to concentrate on was what I wanted to say. That was the gift he gave me. To this day, I’ve never “thought about” how I’m writing what I write, all I do is write. The sentences that Mr. Lockhardt taught me to write just appear on the page because the act of making them is so instinctive.

I do spend a lot of time thinking about what it is that I want to say, but I don’t have to think about how to say it. Mr. Lockhardt took care of that.

What a compliment to you that he had saved all your articles! I’m glad you were able to locate him to close the circle.

We should raise statues to Mr. Lockhart - and my Mr. King in 9th grade, who told our class the first morning of my first day that we were going to learn how to WRITE.

Teachers should be celebrated - and this piece is everything, his methods, his simplicity, his appreciation and finally that visit you had an opportunity to experience and kindly report.

Reading your writing is a tribute to him. And Lucien, thank you for sharing your life experience with us.