She asked the question that changed my life: Betty Prashker, dead at 99

There aren’t many people who can point to a single moment in their life that changed everything. Quarterbacks who took the ball from the center with only seconds left on the clock and threw the pass that won the game come to mind. So do mathematicians who finally write down the last few figures in an equation that solves a seemingly impossible theorem. Holding an infant son or daughter who has just been born is another.

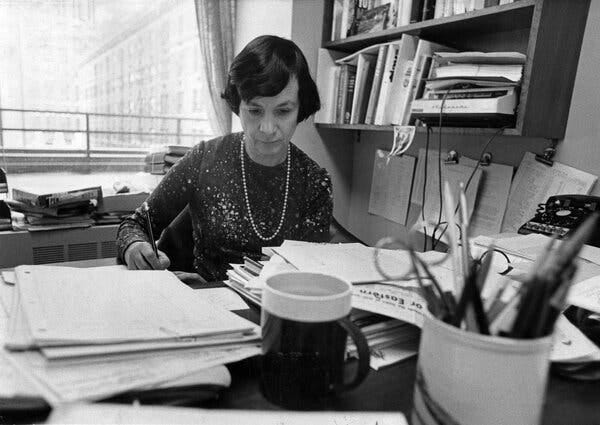

Betty A. Prashker, who died at the home of one of her children at age 99 on July 30, asked me a question that changed everything for me 47 years ago in her office at the New York publisher, Doubleday. The New York Times devoted nearly two-thirds of a page to her obituary today, and she deserves every column inch.

She is described by the Times as an indefatigable advocate for women in publishing and for equal pay in an industry that was a paragon of patriarchy when in 1945, she became a reader of unsolicited manuscripts from “the slush pile,” as it was called in publishing. After taking time off to raise her three children, she went back to work at Doubleday in 1963, when the editor in chief of the publishing house, who she had worked for before, took her to lunch and offered her a job as an editor because Doubleday was under pressure from the government to have more women “in our group,” as she recalled in an interview with the Times. She remained an editor at Doubleday for the next 21 years, rising through the ranks to become a senior editor in the 1970’s, where she was when I met her.

I was working for the Village Voice as a staff writer, and in the lower right drawer of my desk, I had a stack of letters from editors at publishing houses who had written me to ask if I was interested in writing a book. Yes, such a thing happened back when publishers were looking to the Voice and its writers for books on the counterculture and topics the uptown editors thought would appeal to young readers. I didn’t answer any of the letters. I wasn’t a counterculture writer, and I figured if any of the big-time editors from New York publishers really wanted something from me, they would do more than write a one or two paragraph letter.

Betty Prashker never wrote me a letter on Doubleday stationery asking me if I had any book ideas. One day at the Voice, the guy at the reception desk on the writers’ floor, who happened to be James Wolcott (who would go on to become a columnist for Vanity Fair and write books of his own) yelled through the door, “Hey, Lucian, somebody for you on line two.” I picked up the phone and heard a woman’s voice. “Is this Lucian Truscott?” she asked. Her voice was high-pitched and soft, as if she was whispering into the phone. When I answered yes, she told me she had been reading my articles in the Voice and wanted to talk to me about writing a book. I told her I didn’t have any ideas for a book. Assuring me that was okay, she said, “I want to take you to lunch. Are you free on Friday at one?” When I said yes, she told me to meet her at La Grenouille on 52nd Street. “Do you have a tie?” she asked. I said I thought I could scare one up. “Well, if you can’t, they have some in the cloak room.”

And so began our semi-annual lunches at some of the better French restaurants uptown. She would call in the early fall, in September or October, or in March or April, and when I answered, she would say, “Isn’t it about time for one of our lunches, Lucian?” We would talk about the series of articles I had done during Watergate on Bebe Rebozo, Nixon’s bagman, or a personal piece I had written about my great aunts in the Randolph family in Charlottesville, Virginia, or whatever I was writing about that fall or spring.

And then another six months would go by. In 1976, I was awarded a grant from the Alicia Patterson Foundation to write a series of reports about my class at West Point. The previous year, about 50 percent of my class had resigned from the army on the date that their five-year service obligation expired. The reason for the mass resignation could be written with a single word, “Vietnam,” but I convinced the Patterson foundation there was more to it than that, and I got the grant. I wrote my dozen reports for the foundation, a few of which I published in magazines. All the reports were printed and circulated to a list of people the foundation considered influential that included members of Congress. Betty was on the list, so were other editors and publishers.

In early 1977, she called earlier than usual, inviting me for lunch in January or February. She had the stack of Patterson Foundation reports with her in a thick folder. When we sat down, she put her hand on the folder and said, “You know this is a book, don’t you?”

I did. We talked at lunch about how the reports could be turned into a book. I had some ideas. So did she. Right there at lunch, she offered me a book contract.

A week or so later, she sent the contract to me at the Voice. I didn’t have an agent, but I had talked with other writers who had written books, or were writing them, and I knew that publishing contracts were mostly boilerplate. What mattered was the advance you got, the money publishers paid upfront which would hopefully be recouped by the first royalties you got when the book was published. My contract was for $20,000, which seemed like a lot to me. I had been earning about $5,000 a year at the Voice. When magazine money was added in, a good year for me amounted to about $10,000 or a little more, so I was happy with the contract.

Until I got to its so-called indemnity clause. That is where the publisher and author come to an agreement about sharing the costs of litigation if there is a lawsuit against the book, for, say, defamation. Usually, the author and the publisher are, as they say, joined at the hip in fighting the lawsuit and defending the book’s accuracy.

Not so with Doubleday. Their clause allowed the publisher to sever itself from the lawsuit and come to an agreement over liability or damages separate from the author. That meant if I was sued by any one or more of the subjects of my non-fiction book on my West Point class, I’d be on my own when it came to lawyer’s fees in fighting the suit and damages if it was decided against me. Worse, in my view, was that Doubleday’s contract allowed it to issue a retraction or apology or whatever they agreed to do without even consulting me, and they could also withdraw the book from publication without my agreement. As I soon learned, Doubleday’s was considered the worst indemnity clause in the publishing business.

I called Betty and told her I had some concerns about the contract. She asked me to come to her office, so that same day, I sat down and asked if the indemnity clause could be negotiated. Not a chance. Doubleday has never changed that clause for any author, and they won’t change it for this book. We talked for a few moments about the unfairness of Doubleday’s position. Then I put the contract on her desk and said I couldn’t sign it. We shook hands, and she said she was sorry.

I turned to leave her office, and just as I grabbed the door handle, I heard her voice behind me: “Loooshan?” She had a way of stringing out my name when she wanted to charm me. “Have you ever thought about writing a novel?”

I turned around. She was standing behind her desk with a little smile on her face. “No, I haven’t,” I answered.

“Well, if you did, what would it be? she asked.

Without a pause, I said, “How about a gay murder at West Point?”

Betty picked up the contract and waved it in the air. “Come back here and sign this contract,” she said, and not in her whispery voice.

I walked across the room. She had put the contract down on her desk and was holding a pen. “But Betty, it’s for a non-fiction book. I would be writing a novel.” Then it came to me that the indemnity clause wouldn’t apply to a novel because I would be protected by one of those “all characters in this book are fictional” statements at the beginning of novels. I asked her if that was true.

“Yes, it is, so just sign right here,” she commanded.

“But what about the title and the description of the book? Isn’t that going to be a problem?” I asked.

“You let me handle that. Just sign the contract. I’ll get you the first part of the advance right now, and you can walk out of here with a check.”

I signed a contract for a non-fiction book called “Generals and Other Victims” and wrote the novel that became “Dress Gray.” I wrote the book that summer and fall in Sag Harbor, handing over the manuscript 200 pages at a time to Betty, who had a house in Water Mill. It was a Literary Guild Book Club selection, sold to Warner Brothers where Gore Vidal would be hired to write the script, and when the paperback rights were sold, it made Page Six in the New York Post. The book reached number three on the New York Times bestseller list. That single question asked by Betty had changed my life forever.

We did another book, “Army Blue,” when she moved to Crown Publishers as a vice president and editor in chief. I introduced her to Dominick Dunne, and she published his first novel, “The Two Mrs. Greenvilles,” and his other books, every one of them a bestseller. I had moved away from New York by then, but every time I came back to town, whether we were working on a book or not, Betty would take me to lunch at the Grill Room in the Four Seasons. The young woman who had started out reading unsolicited manuscripts by nobodies had a regular table for lunch every day and was known by everybody at the Four Seasons -- Wall Street titans, movie studio executives, publishers, newspaper editors. They all stopped by her table to whisper in her ear and be introduced to “one of my authors,” me. She was a force of nature, and she made her mark at a time when women in New York publishing were as scarce as ice in the Sahara. I’m proud to have known her and to have been one of her authors.

It's a glorious piece, sadly born from Betty Pashker's death. There are two sentences which are especially smile-worthy: "Just sign the contract. I’ll get you the first part of the advance right now, and you can walk out of here with a check." For a freelance writer, then, to get a check put in your hands on the spot? We're talking serious heaven.

Ms Prashker was what the founder and dean of my professional school, the late Dr Alden Haffner would call a "change agent". Somebody who often meets people and changes their lives in the process. They walk among us and you don't know who they are. They are often not well known, but they've touched the lives of many people in ways that they can never repay. Dr Haffner had always urged us to become change agents to better the world we live in.