In 1948, I accompanied my mother on a voyage from Japan to San Francisco on a troop ship that lasted 28 days and should have qualified her for sainthood, or at least free drinks at every Officer’s Club she ever walked into for the rest of her life. The ship was about the size of the cork in a bottle of wine and pitched and bobbed like one, or at least I was told that by my mother when she saw fit over the years to remind me how much I owed her for putting up with the “first sergeant” all the way across the Pacific. In later years, she admitted that the presence of a baby was so unique that the ship’s crew and the soldiers aboard took care of me for most of every day, so she was stuck with me and my considerable lung-power only in our stateroom at night.

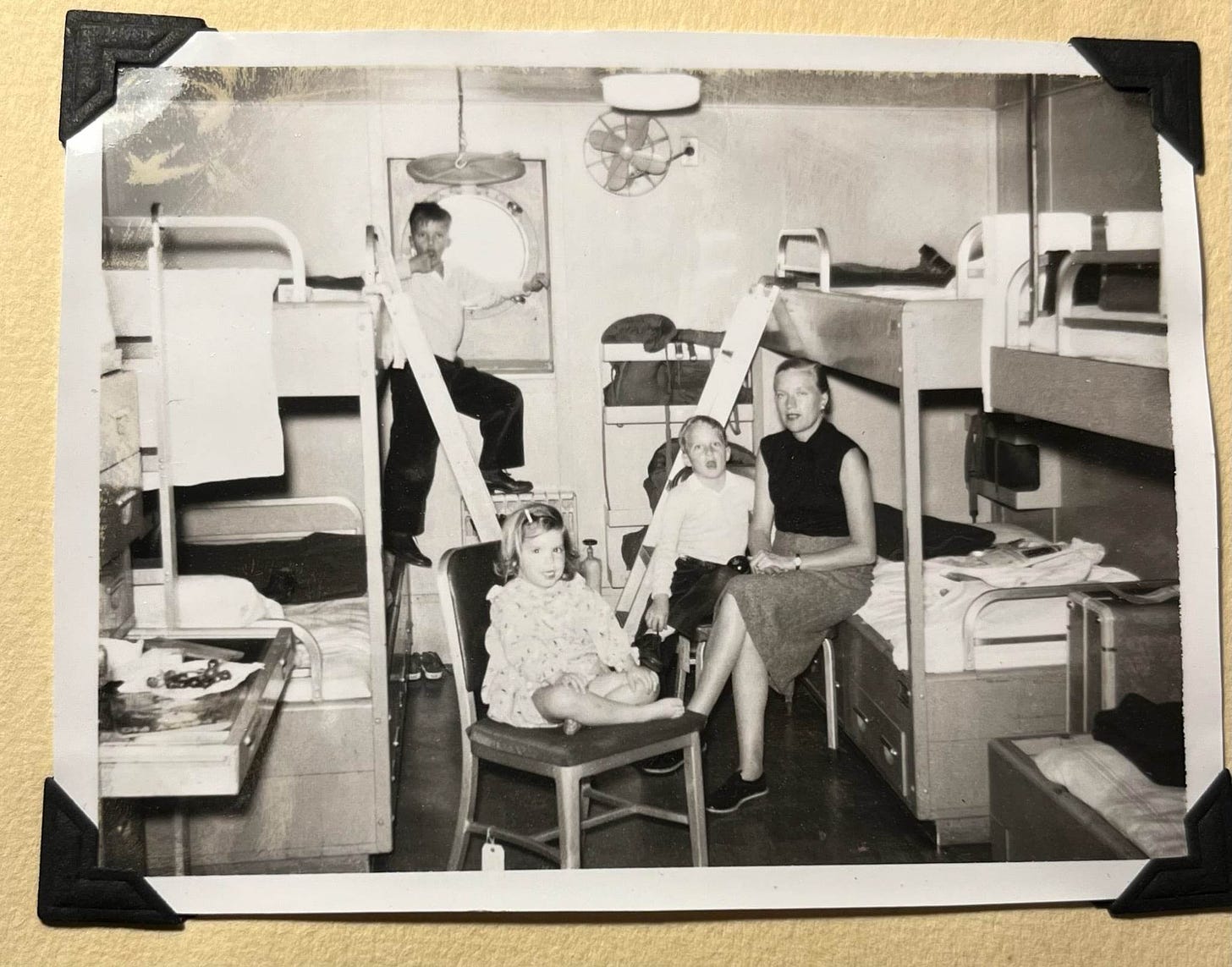

To give you an idea of the luxury accommodations afforded military dependents traveling across the oceans in those days, here’s a picture of our family on the SS Patch, another troop ship, on our way to assignment in Germany in 1955:

L -R, that’s me next to the open hatch, my sister Susan, my brother Frank, and my mother. Judging by our attire, the bell for dinner must have just rung, and we were ready to go up for the relatively formal evening meal they served nightly on the SS Patch.

Anyway, back to the origin story —

We moved around the country constantly after returning to the States. By the time I left home at 18, my mother figured we had lived in 22 different dwellings, including a converted World War II-era hospital wing at Fort Benning, GA, a metal Quonset hut in San Antonio, TX, during the summer, a converted WWII barracks at Fort Leavenworth, KS, and converted Nazi-era military housing in Oberammergau, Germany.

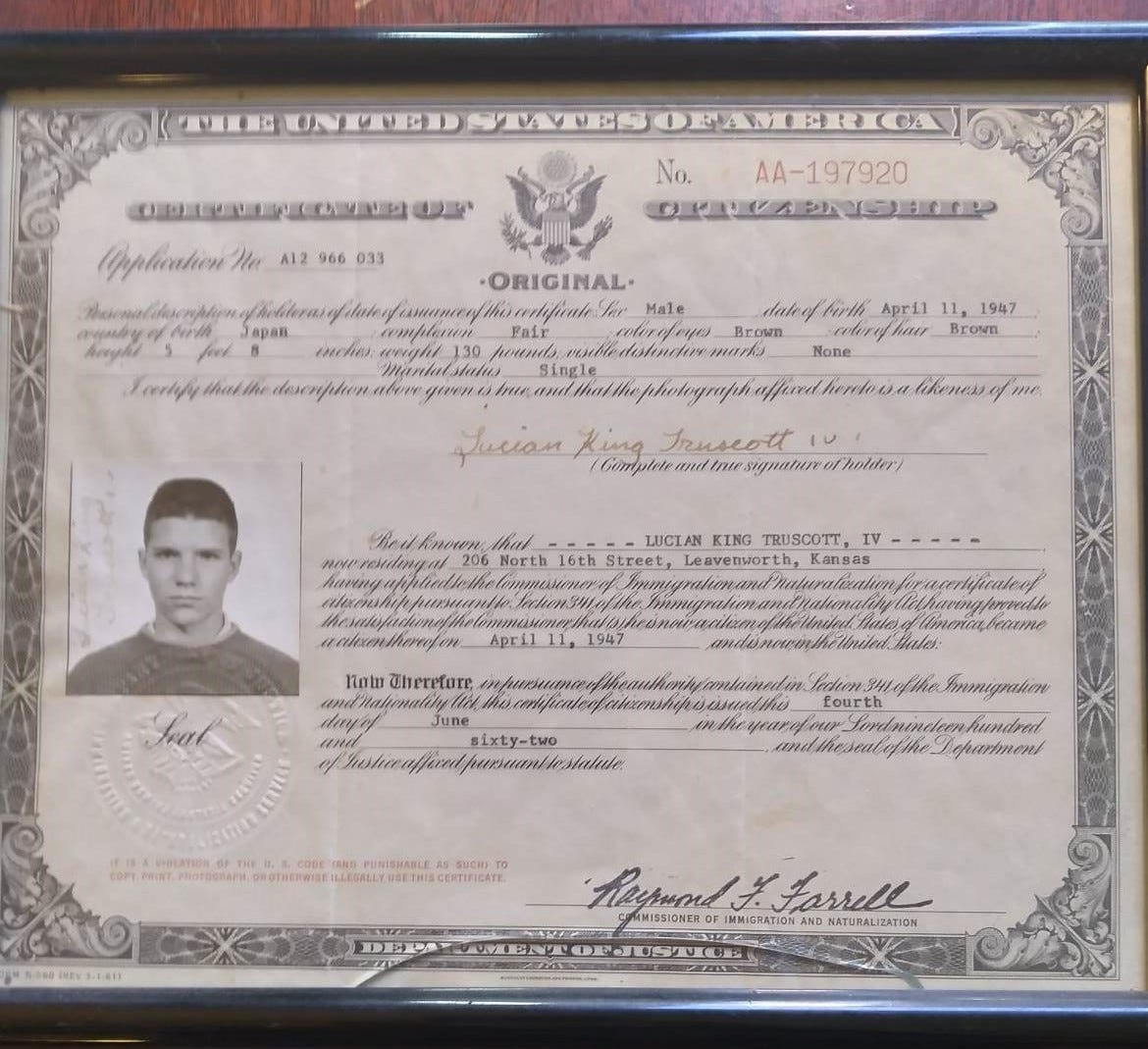

It was during the year we lived in downtown Leavenworth while my father was stationed in Korea in 1962 that the story of my life took an unexpected turn. One day, the government of Japan informed the Department of State that they were claiming Japanese citizenship for the 30 or so children born after the war in Japan before there was an immigration treaty between the two countries. That very day, the State Department called the parents of all the affected children and informed them of this unexpected diplomatic emergency. My mother drove down to Leavenworth Senior High School, took me out of class, and drove me to Kansas City, where under instructions of the Department of State, a federal judge was waiting for us in his courtroom. I raised my right hand, swore allegiance to the United States of America, and became a citizen.

I don’t know why the Department of State didn’t tell the government of Japan to take its claim of citizenship over a bunch of American kids and shove it up their ass. After all, Japan had waged an undeclared war against the United States, killing thousands of American soldiers, and lost. Maybe it was a kind of diplomatic macho move by Japan to remind the nation that had conquered them and written their Constitution that, hey, we’re a country, too. The whole thing was never explained to me, but I’ve held onto my citizenship papers, shown above, ever since.

My citizenship certificate has proved necessary several times over the years because I don’t have a birth certificate. The Army wasn’t prepared for the birth of babies in occupied Japan. The only proof I have of my birth is a Department of Defense medical form that shows my mother entering care at the Fukuoka field hospital on one date, and her discharge on April 16 along with the discharge of one child, Lucian K. Truscott IV. The DD hospital form proves she entered the hospital by herself, and came out carrying me. In the interim, I emerged into the world.

I had a similar experience at the age of five. My dad, a USAF captain, had been transferred from Kelly AFB, San Antonio (we have that city in common) to Chicksands Priory. a joint RAF/USAF post in Bedfordshire, England. He went over by plane before us to secure living quarters -- half of a thatch roofed cottage he sublet from a British Army officer who had been sent to Germany -- and Mom and I went to join him by ship. We boarded the S.S. Washington at New York in December for our voyage to Southampton. We were given bunks in a cabin we shared with two other women and either two or three children. We were greeted by our cheerful Filipino cabin steward, who introduced himself as Juan, making me think that "One" was in interesting name. All went well until we were out into the ocean and sailed into the teeth of what I was later told was the worst winter gale on the North Atlantic in 25 years. I got violently seasick. The ship's doctor said, "Feed him." Whenever we got close to the dining room and I smelled food, I would start retching. This lasted for about three days. The weather cleared, we made port and were greeted by my dad, who took us in his new Austin A-40 car to our home on a dairy farm in Hertfordshire. So began two delightful years in which I began my formal education in a county council school, where being American probably saved me from having my bottom caned by the formidable headmistress, Miss Brooks, who had climbed the Matterhorn and survived an early round or two at Wimbledon. Instead, my mother got phone calls.

Hi Lucian,

I also was born in 1948. My mother's fourth child, I was the first born with my father in town. He was Annapolis class of 1937, in Pacific in submarines throughout the war, got out in '46, as he put it, "because your momma couldn't handle three kids without me at home." She enjoyed telling the story that she got to the hospital fine for the first 3 births, but my father was in such a hurry driving her to hospital when I was about to arrive that he ran a red light and caused a car accident. He would respond, "Yeah, the boy's been a problem for me since before he was even born."

My wife, Tori, and I had dinner with you, Tracy and Doug Jeffrey and Ellen shortly before you left Hamptons for Pa. I continue to enjoy your writing.

Don Matheson