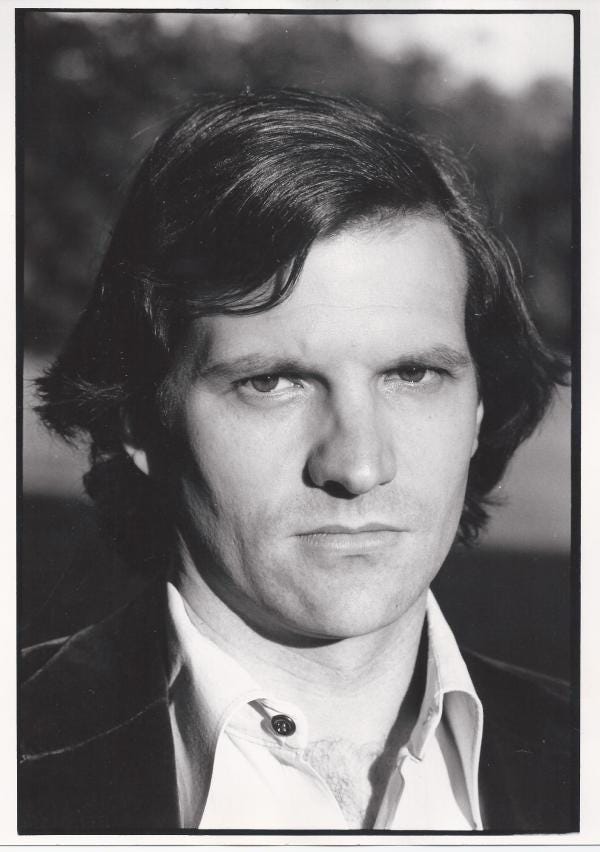

The author at the height of his hair years.

Yes, that’s your humble correspondent in the photograph above…or maybe not so humble by the look on my face, come to think of it. It’s one of the photos taken by Fred Seidman for my first novel, “Dress Gray.” It wasn’t hard to find someone to take my author photo way back when. Fred was dating my then-girlfriend Carol Troy’s best friend Mary Peacock and working for the short-lived but magnificent fashion magazine Carol and Mary co-edited, Rags. Of course he was. Everyone knew a talented photographer, or was dating one, or used to date one, or was working as a stylist for one, or knew a model who was posing for one, just like everyone knew a talented singer, or had a friend who was in a band, or maybe their ex-boyfriend was an off-Broadway actor, or they were dating a dancer in the Joffrey Ballet or an editor at Random House or a writer for Vogue or an artist showing at a gallery on Greene Street or an editor at the Times or even Abbie Hoffman’s accountant.

That’s the way it was in the 70’s in New York. You could afford to live in the city back then, and every other person you passed on the street in the Village was someone you knew. We existed in a narcissistic world of each other – leggy girls in black mini-shirts and knee-high boots and formless peasant tops, guys in fringed-leather jackets and rough-out cowboy boots and faded jeans, all of us moving headlong into a future we just knew held promise not only for ourselves but for practically everyone we knew. It seemed like all of us were young and busy and driven and filled with hope and opportunity, or maybe that was because our radars were tuned only to each other. You’d turn the corner and someone would invite you to dinner or give you a ticket to see this new hot guy named Springsteen at the Bottom Line or a free pass to a movie premier or an invitation to an art opening on West Broadway.

Or you’d get home and your phone would ring and an old high school buddy would be telling you about the new job he’d just scored as Paul Mitchell’s accountant and manager, and man, you’ve got to get up here and check out his salon, man, the place is crazy! Which is exactly what happened to me one afternoon when I walked into the loft carrying my mesh shopping bag filled with stuff I’d picked up for dinner on the way home from the Voice. Of course an old buddy would be working with the hottest hairdresser in Manhattan! Of course the place would be as crowded with models as a subway car full of commuters at rush hour. You didn’t even think twice about it, because when you were young and on the move in New York City, that kind of thing happened daily.

Hairdressers had recently started to become celebrities and Paul Mitchell was one of them. You’d see mentions of him on Page Six in the Post, in Liz Smith in the Daily News, even in the style pages of the Times. Suddenly there was a Paul Mitchell “cut.” I think I first heard the words, “wash and wear hair” from someone who had gotten a Paul Mitchell cut. Now, according to my friend Frank Wasuta, who had been a wrestler and something of an operator when we were seniors at Mount Vernon Senior High School in northern Virginia, Paul Mitchell had moved his salon uptown to 58th Street, on the block between Madison and 5th Avenue, a hot piece of real estate just around the corner from upscale joints like Tiffany’s and Gucci and Saks Fifth Avenue and Bergdorf’s and Bonwit Teller.

Wasuta kept calling me and telling me I had to get myself uptown and check out the scene, which he described as “unbelievable.” “Models are dripping down the walls, they’re falling out of ceiling vents, man, the place is a riot of hot chicks. There’s even a coke dealer in an upstairs apartment keeping everyone supplied.” Which wasn’t surprising, since everyone had a coke dealer upstairs in those days. I explained to him that I had a girlfriend and we lived together and the whole I’m-settled-down-now thing, but Wasuta insisted. “If only recreationally, you’ve got to check out Paul’s scene, man. He’s a cool guy, the salon is out of control, you won’t believe it. I’ll even get you a free haircut, man.”

I got my hair cut at a joint on 8th Street in the Village, and I had never had my hair styled at a real uptown salon by a hot hairdresser. I decided I’d give it a whirl, so I jumped on the uptown subway and got off at 57th Street and made my way over to 58th and found the Paul Mitchell salon in a space that had been punched through to connect the second floors of two buildings. The place was called “Superhair,” and was pretty much like Wasuta described -- all-white, with chrome chairs mounted on little chrome bell pedestals in two rows down the sides of a long, narrow room festooned with palm trees and hanging ferns. Wasuta took me through a door to the other room which was being used to train new hairdressers and for storage. Frank was living in a studio apartment in the back, which he described as a really good deal: he wasn’t paying rent and he was meeting tons of girls.

Paul Mitchell was a Scotsman who got his start working for Vidal Sassoon, probably the first celebrity hairdresser, in London. Sassoon sent him to New York in the mid-60’s to help open his first American salon. Mitchell quit working for Sassoon after a few years and opened his own place as a stand-alone salon within Henri Bendel called Crimpers. He opened satellite salons in other major cities, including his own flagship shop on St. Marks Place before moving uptown to open Superhair in 1972. The main part of Wasuta’s job, as it turned out, was to help Mitchell start up his own line of haircare products, which eventually became ubiquitous in their white cylinders with his name lettered in black down the sides.

Wasuta described how he had been juggling Mitchell’s books so he could float the money necessary to manufacture shampoo and conditioner at a factory over in New Jersey. They were already selling the products out of the 58th Street salon, but Mitchell knew that wasn’t enough to really get his product line going. He and Wasuta came up with a plan to take his show on the road by advertising appearances in cities around the country at which he would teach his signature Paul Mitchell “wash and wear hair” cut to hairdressers at the same time he would wholesale his products to them for sale at their salons.

There was only one problem, Frank explained to me over drinks in his backroom apartment that afternoon. Michell couldn’t get a bank to loan him enough money to manufacture the products, take the show on the road, and run the salon at the same time. Something was going to have to give if they were going to make it to the next step, which was selling enough of his products to support the manufacturing and roadshow end of the business. The salon itself was going gangbusters, which I could see as I walked through the main room, crowded with models and uptown wives and professional women eager to have their hair styled with Mitchell’s easy-care cut. He was earning enough with the salon every week to make enough product to take on the road and sell every weekend. It was the salon’s payroll that was the problem. Wasuta said they could get the roadshow going if he could borrow enough to make the payroll every other Friday. All they needed was a loan to carry them over every other weekend, but banks weren’t interested. Did I know anywhere he could get two thousand by Friday? Wasuta said he could pay $500 interest by Tuesday because of the land-rush business they did on Fridays and Saturdays.

Well, it so happened that I had just landed a check for $2000 for a piece I wrote for Oui Magazine, I told him. Five hundred bucks? That’s loan shark style interest. Are you serious?

“You give me two-grand on Friday so I can make the payroll, and I’ll give you $2500 on Tuesday morning when we open, 10 sharp. You know me, man. I wouldn’t take your money if I wasn’t going to cover you.”

And that’s the way I became Paul Mitchell’s loan shark. Every other Friday morning I withdrew $2000 in cash from my bank on 6th Avenue. I jumped on the subway at West 4th Street, made it uptown, walked across 58th Street to the salon and delivered the cash to Wasuta. “You want to go with us this weekend and watch your money at work?” he asked one Friday. They had been running ads in newspapers all over Connecticut. They would hit New Haven on Sunday and Hartford on Monday, because those were the off-days for hair salons. They would be back in town in time to start cutting hair on Tuesday. He would deposit the salon’s Friday and Saturday take that morning and get my money for me. Sure, I said. Why not?

I had an old ’64 Pontiac Bonneville Sport Coupe I had bought when I lived on the barge in New Jersey, so Wasuta and I drove up to New Haven day in time to meet Paul and the truck they had rented. We helped them unload at an old movie theater they had leased in downtown New Haven. The truck carried enough stuff to transform the stage into a set resembling the Paul Mitchell hair salon in New York: three chairs on their chrome pedestals, an entire sound system with a tape player and amp and mics and speakers that went on either side of the stage, and a backdrop painted with the name Paul Mitchell in the same lettering that was on the sides of the bottles of shampoo and conditioner, plus a half dozen or so palms to give the stage some color.

The advertising had worked, because by 3 p.m. or so, the theater was filled with hairdressers eager to learn from the master. I was backstage with Wasuta. He pressed play on the tape machine and something hot from the Rolling Stones filled the theater and Paul bounded onstage in sharp black trousers, a form-fitting black shirt, wearing a neck-mic and greeted he audience in his signature Scottish brogue: “Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to Superhair New Haven!”

And off he went, a natural born performer. Within minutes, he had three women shampooed at a sink that had been rigged up on the stage, they were in the chairs and Mitchell was bounding between them like Edward Scissorhands Baryshnikov, his fingers moving with such speed that hair flew from three heads at once. He whipped his blow-dryer around on its cord like Roger Daltrey did with his mic, catching it just in time to blast the back of a head or fluff the shag-cut sides. He was masterful, and he kept at it, throwing in patter about his new line of shampoos and conditioners as he went: he had them for dry hair, oily hair, thick hair, thin hair, you name it and Paul Mitchell had a shampoo for you and a conditioner to match.

By the time he was finished a couple of hours later, he had cut 9 or 10 heads of hair and the hairdressers and salon owners were lined up at the side of the stage where Paul himself was selling them whole boxes of his products. Wasuta and l looked at each other. This thing they had come up with was working!

We spent the night in a motel and hit the road for Hartford in the morning and did the whole thing over again Monday afternoon. As Paul Mitchell’s “roadies” packed up the set and got ready to drive back to the warehouse space they had rented in New Jersey, I drove Paul and Frank back to the city. Frank didn’t say a word about the “arrangement” we had made on Friday. He had explained that Paul wasn’t much of “a numbers guy.” As long as the show hit the road and he was back to cutting a dozen or more heads a day by Tuesday, Frank explained, everything would be cool.

That’s the way it went for almost a year. I would loan $2000 to Paul Mitchell every other Friday, and Wasuta would hand me $2500 in cash the next Tuesday. My deal with True had run out, but I was still making $80 a week at the Voice, and now I was pocketing a grand a month as a loan shark.

Paul Mitchell did cut my hair a couple of times; and I have to tell you, they were without a doubt the best haircuts I ever had. These days who cuts what’s left of my hair is hardly an issue, but I look back on my hair days with great fondness…except for the abject stupidity of loaning all that money to Paul Mitchell instead of putting a couple thousand into buying an owner’s share or two in his haircare company.

Had my brain not been raging with the overheated hormones of a 24 year-old, I would probably be writing this Newsletter, if I was writing it at all, under the shade of an umbrella on a patio with a view of my own private beach in Eleuthera.

Aaahhh, youth, when I had plenty of hair but absolutely no sense.

Heidelberg 1974...an English friend Malcolm who sold Belgian rugs all over the US bases at weekend bazaars rounded up a few of us to help out his girlfriend's hairdresser.

Seems they had no customers with short hair to train their staff...Americans to the rescue!

Edward Scissorhand Baryshnikov. Nice.