In 1958, Al Kooper, the famous musician, songwriter and producer, was a guitarist from Brooklyn, New York, starting out playing with the Royal Teens. They became famous for recording a novelty song that became a hit that year, “Short Shorts.” Kooper was only 14 years old when the Royal Teens made it, and he didn’t even play on the recording session for the song, but it got him started in what was then called “the record business.”

In 1960, he co-wrote “This Diamond Ring” for Gary Lewis and the Playboys, and “I Must Be Seeing Things” by Gene Pitney. At 21, he moved to Manhattan and started hanging out in the Village and getting work as a session player. Playing sessions at CBS recording studios, he met producer Tom Wilson and got him to record a few of his songs.

In 1965, Kooper was at CBS recording studios when Wilson asked him if he wanted to come to a Bob Dylan session later that week. “I hear you’re a Dylan fan,” Wilson said to him. “Thursday, two o’clock. Studio B.” Kooper recalled later that he showed up early with a plan to see if he could sit in on the session as a guitar player. “I was just going to go and tell him (Wilson) I misunderstood and thought that he had hired me to play on the session.”

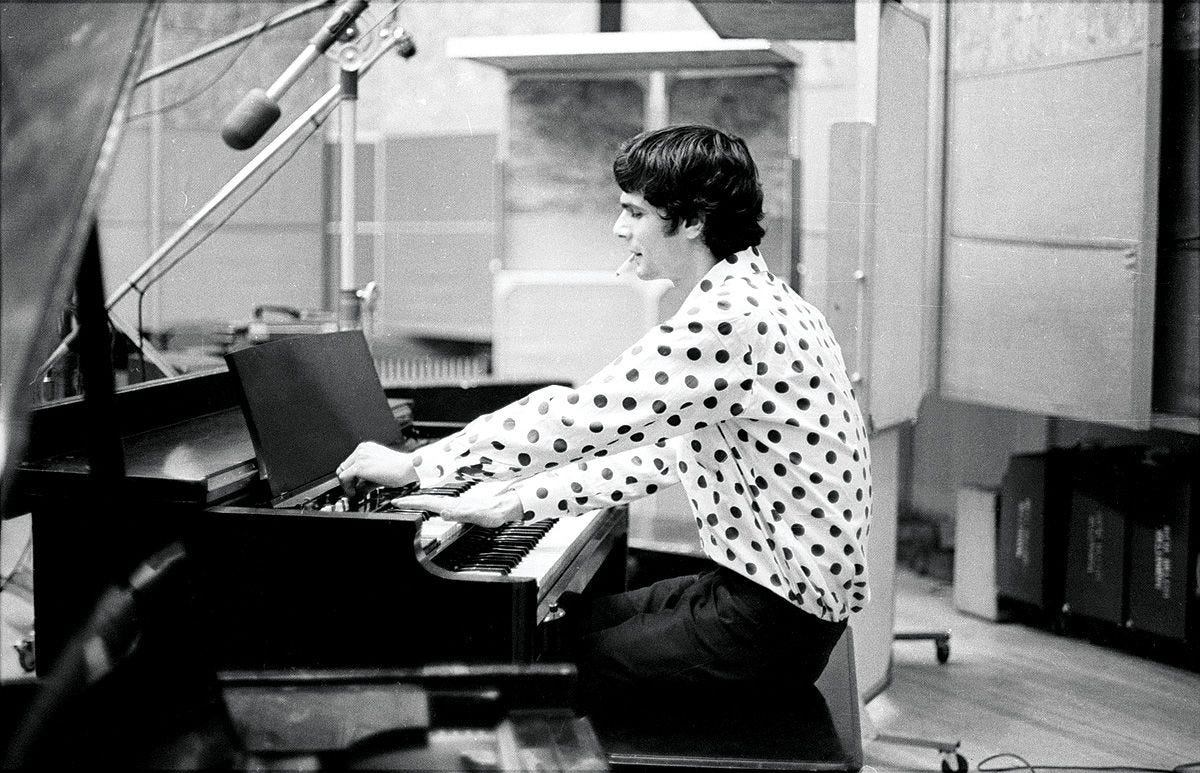

Kooper sat down in the studio with his guitar and was starting to warm up, when the real guitar player who had been hired for the session showed up and sat down next to him and plugged in and began his warmup. “He was about 50 times better than me, just warming up, so I unplugged and took my guitar and left the studio.” Kooper was in the control room putting his guitar in its case when he noticed that they had moved the organ player over to the piano. Realizing that producer Wilson hadn’t seen his failed attempt to sneak into the session previously, Kooper asked him if he could play organ, telling him, “I’ve got a great part for this song, which was a total lie. I didn’t have nothing.”

Wilson said, “Sit down, Al, you’re a guitar player.” Kooper thought it was over when Wilson took a phone call. “I thought, well, he didn’t say no,” so Kooper went into the studio and sat down at the Hammond B3 organ. “It’s a real difficult instrument to turn on, you have to do all these things, and I was just praying that the guy had left it on, and he had,” Kooper remembered years later in an interview with the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum. “Nobody looked at me funny, so I just sat down at the organ, and Tom came back into the control room and said, ‘Okay, this is take two…hey, what are you doing out there.’ That was the moment when this story could have turned out different, but he just said, okay, here we go, and he gave me a chance.”

Kooper had never played the organ before, but remembered that there were only four chords in the song. He had an additional problem: he couldn’t hear the organ, because the organ’s Leslie speaker was all the way across the studio covered with a blanket, so its sound wouldn’t leak into the other musician’s microphones. The sound wasn’t very loud in the headphones, either, and the guitar was mixed very loudly, “so I couldn’t hear what I was playing,” Kooper remembered. “So I had to play by looking at my hands and knowing what notes to play. Fortunately, there were only four chords in the song, so when I was playing, I would wait an eighth note before I came in to make sure it was the right chord. Because I didn’t want to be the one who made a mistake, especially since I was doing this commando raid on the organ. So, it turned out to be the only complete take of the day, that take.”

Afterwards, producer Wilson invited the players into the booth to listen to the take. “After about 30 seconds, Dylan says to Tom Wilson, ‘turn the organ up.’ And Wilson says, “Hey Bob, that guy’s not an organ player, he’s just a guitar player.’ And Bob says, ‘I don’t care what he is, make the organ louder.’ That was the take that they kept for ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’ When the session was over, Dylan came over and asked, ‘can you come back tomorrow?’ and I said, absolutely, and that’s how I became an organ player.”

As Kooper recalls, when the song hit the charts, “I became a famous organ player, and my style, which was based on ignorance, became a very copied organ style. This was not wasted on me. I have to say that at that time, when I was 21 and trying to make it in the music business, I believe I was 90 percent ambition and 10 percent talent. It’s totally reversed now. Forty-three years later [at the time of the interview] I think I’m 90 percent talent and 10 percent ambition.”

Al Kooper’s story of how he made it in the record business is my story in the writing game. I’ve written about this before, but it’s worth recounting here how at age 19, I used to take leave as a cadet from West Point and travel down to New York City just so I could sit in Village Voice editor Dan Wolf’s office on Friday afternoons when his office turned into a kind of writers’ salon as Voice writers like Nat Hentoff and Pete Hamill and Michael Harrington and Jack Newfield entered to turn in their copy for that week’s issue. A year after my first trip to hang out at the Voice, I slipped a copy of a letter to the editor under the door of the Voice on a Sunday morning, and the next Wednesday, they ran it on the front page as an article, my Hammond B3 moment in 1967.

Like Kooper, I had way more ambition than talent. My attitude was, if a door is open, I’m going through it, and if it’s closed, I’m giving it a push and going through anyway. That’s the way I broke into writing for the Voice. In 1970, with an assignment for Esquire to interview James Brown during a run of appearances at the Apollo Theater, Brown was giving me the stiff arm and refusing to give me the interview on which my story depended. So, during a week of shows, I had a backstage pass and started hanging out across the hall from his dressing room in a little office where two women from Georgia sat at sewing machines repairing the tight-fitting outfits he constantly split out at the seams during performances.

On the last day before the James Brown show left the Apollo, one of the seamstresses I had gotten to know asked me if I had been able to get into see “Mr. Brown” yet. When I told her no, she grabbed a hanger holding one of Brown’s suits she had repaired and stood up and told me to crawl behind her across the hall and hide under her floor-length skirt. “I’ll kick you when we’re inside,” she said.

She did. When I sprang out from the seamstress’ skirt, notebook in hand, James Brown jumped back in surprise, and then cracked up, saying “Man, you want to ask me questions so bad, you got yourself here, what do you want to know?” I asked him where he learned how to dance, and he said, “I started out doing steps on my momma’s porch in Augusta, Georgia, when I was five or six.”

But getting in the door isn’t enough. Once he talked his way into Studio B at CBS studios in 1965, Al Kooper had to play the notes on that Hammond organ Dylan ended up playing louder so the world could hear them on his first hit record. In his interview with the Musician’s Hall of Fame, Kooper said he had to learn Dylan’s song, so he could play his organ notes even though he could barely hear himself in the mix. But he did more than that, way more. Kooper was living in the Village, hanging out in the clubs on Bleecker and McDougal, wandering through Washington Square Park, checking out the same scene Dylan wrote about in his famous song.

Any time you create something – it doesn’t matter what it is, art or music or writing – you go to a place inside yourself where you can visit your memories and listen to your dreams. But what you find in there isn’t just yourself: it’s everyone you know, all the places you’ve been, everything you’ve seen, all the emotions you’ve felt, and all the stuff that’s been acted on you, from anger to ecstasy to loss to grief, all of it not mixed together, but one by one, if you give yourself the room to re-experience them. Al Kooper’s organ part in “Like a Rolling Stone” doesn’t just follow the chords, although coming in an eighth note late turned out to be genius. His first notes hit you like the sound of a New York street when you walk out the door, a shock that takes you into another world. At the age Kooper and Dylan were in 1965, at the age anyone is when they’re 20 or 21, when you’re young, everything is a new world. Dylan’s genius was to capture it in music, and Kooper’s genius was first, to be there, and second, to sense where his music was going and what it meant.

Kooper knew it came from somewhere, because he was there, in the Village in the early 60’s. He knew the character Dylan was describing, who “used to laugh about, everybody who was hanging out, now you don’t talk so loud, now you don’t seem so proud, about having to be scrounging, your next meal.” It was him, it was Dylan, it was everybody they knew, if not at that exact moment, then over the last few years when all of them were trying to make it. They had all been complete unknowns. They had all asked someone, with their eyes if not their mouths, “do you want to make a deal?” Al Kooper’s commando raid wasn’t an attack as much as it was a plea, and his crying organ brought home that lonely thing of knowing that it was all on you, and yet you were going to have to compromise with others to get where you wanted to go.

The thing of any creative endeavor is how dependent you are on others, and how much you share it with them. In “Like a Rolling Stone,” the chords and words were Dylan’s, the organ notes were Kooper’s. He couldn’t have played them without Bob, but Bob wouldn’t have had “take two” without Al Kooper. The genius of Dylan was to know that about Kooper. The genius of Kooper was not to play the notes, but to get into the studio, and once there, to know where he was and with whom and what it meant.

I have a keyboard that plays letters rather than notes, and for years I was jealous of guys like Dylan and Kooper and anybody else who got to be on stage because they got to do what they did in public. I had a fascination with musicians and what they did for years before I understood that writers like me were doing the same thing. It took me almost a lifetime to get it that I go the same places they go, down inside myself, and I end up finding others in there, too – other rooms, other lives, feelings I can remember that are not my own but I record them anyway. You make it up as you go, you tell the truth even when you’re describing a lie, you play a note that’s sad even when you’re celebrating, and you are always telling a story that is not completely your own.

Al Kooper owes Dylan for his chords, Dylan owes Kooper for his organ notes, and they owe Greenwich Village and youth and ambition and ignorance for letting them take a chance on bending a forbidding world to their will. They both owe their listeners.

I owe my readers, and I owe a lot of editors, at least one of whom I have paid tribute to in this column. I also have a debt to being young and stupid that I pay every day in this column. It has taken me more than 50 years to understand that when I thought I was going deep inside to find myself, what I found instead was my mother and my father and, yes, Al Kooper and Bob Dylan and everyone else whose path I crossed over the years.

I owe you all.

It's our joy and privilege to have your articles to read and remember and share our comments

Lucian, you are one of the best writers I know. I only wish I could write as well as you.

Thank you for another wonderful column. While I enjoy the hell out of your political writings, it’s your memories and personal recollections that get me every time.