If you are lucky in your life, you come to know one or two people who made you who you are other than your parents who gave you the extraordinary gift of life. Edwin Fancher, who it is my sad duty to inform you died last Wednesday in his apartment on Gramercy Park at the age of 100, is one such person in my life. He was one of the three founders of the Village Voice, the Greenwich Village weekly that became known as the nation’s first alternative newspaper. The Voice, and he, were so much more than that.

Fancher, was born in 1923 in Middletown, New York. His father, Frank, was the vice president of the Orange County Telephone Company. His mother, Elizabeth, was a homemaker. He went to college in 1941 at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. When the war broke out the following year, he enlisted in the Army and joined the Infantry.

The co-founders of the Voice, Daniel Wolf and Norman Mailer, did pretty much the same thing: they volunteered for the Army straight out of college and after Basic Training, went into the Infantry. Fancher served in the storied 10th Mountain Division in Northern Italy, more about which below. Wolf served as an aerial reconnaissance specialist in Papua, New Guinea. Mailer served in the 11th Cavalry in the Philippines. All three men saw combat during the war.

After the war, they returned to New York. Fancher and Wolf met at the New School in Greenwich Village when they were student there. Wolf and Mailer were roommates in an apartment on First Avenue, where Mailer wrote his first novel, “The Naked and the Dead.” Wolf introduced Fancher to Mailer, and ended up introducing Mailer to Fancher’s girlfriend, Adele Morales, who three years later became Mailer’s second wife. Greenwich Village after the war was a small town within the big city of New York filled with artists, intellectuals, and writers. As Fancher and Wolf both told me later, and as I came to know when I moved there myself in 1970, everybody knew each other.

In 1955, Fancher and Wolf came up with the idea of starting a weekly newspaper, which they named the Village Voice. Mailer and Fancher invested $5,000 each in the new venture. Fancher, who was finishing an internship in clinical psychology, agreed to work part time as the publisher while he began his practice as a psychologist. Mailer wrote a column for the paper. Wolf became the paper’s editor.

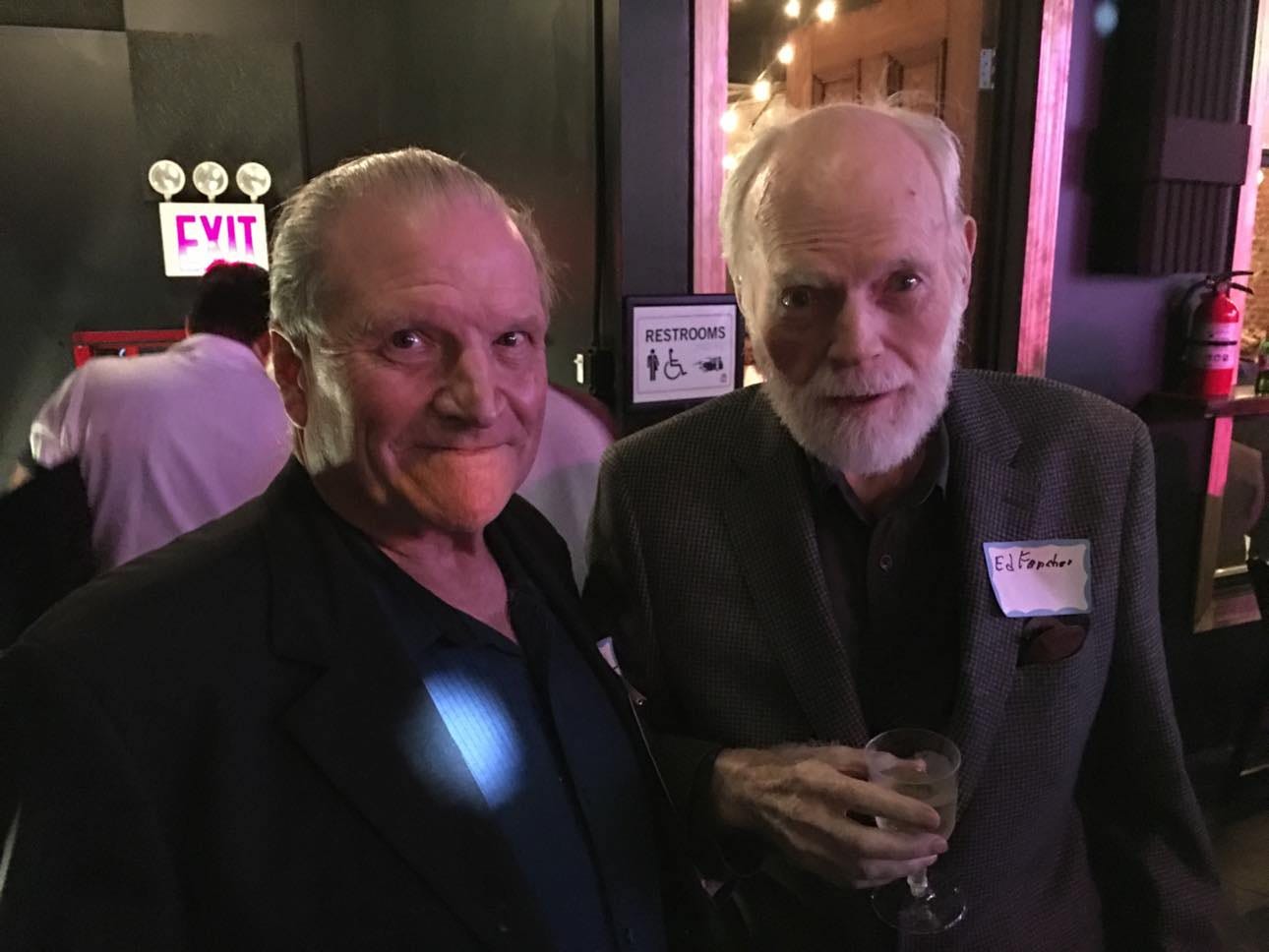

Fancher, speaking at a reunion of Village Voice writers and staffers in Tribeca in 2017, described the early years of the Voice as a week-to-week struggle. Fancher was in charge of ad sales and distribution of the paper. He told the gathering of Voice veterans that starting the paper came straight out of the three men’s experiences in World War II. They had survived the war and wanted to start a paper that reflected their belief in a free and open society. They were “optimists,” Fancher said, who wanted a newspaper that would be open to new ideas, and new ways of reporting.

Wolf and Fancher saw the Voice as a “writer’s paper” rather than as a paper driven from the top down by editors. In the early days of the Voice, they couldn’t even afford to pay writers. After the paper started to make some money, they paid $10 for freelance articles, and practically every piece in the Voice was written by a freelancer. The idea that the Voice was a writer’s paper grew out of the days when the Voice struggled. Who were they to tell writers what to write, when they could barely pay them?

Although the Voice would become known as a leftist paper, and in later years as a counterculture paper for its coverage of liberal politics, pop art, rock and roll and off Broadway plays and playwrights – the Voice founded the Obie Awards for off and off-off Broadway productions – the paper wasn’t intended as a paper that pushed any one ideological viewpoint. The politics of the paper were the politics of the writers, and it so happened that many Voice writers came out of the scenes that they covered, from culture to politics. Jonas Mekas was an underground filmmaker who also covered the underground film scene. Other Voice critics were playwrights and dancers who wrote about those scenes. The famed Voice City Editor, Mary Nichols, started writing for the Voice when Wolf got tired of being asked by her to publish stories critical of Robert Moses’ project to build the Lower Manhattan Expressway that would take out a large chunk of the South Village and what became Soho. He told Nichols if she was so obsessed by the issue, she should write about it herself, so she did.

The 1963 newspaper strike in New York City, which lasted for more than 100 days, was the breakthrough the Voice needed. With nowhere else to place their ads, businesses flocked to the Voice to advertise. The Voice also broke through a stranglehold the big newspapers held on newsdealers during the strike and distribution soared with few other newspapers to sell. The storied investigative reporter Jack Newfield was hired by Wolf in 1964 to write stories that combined his political activism with his writing, and other writers with a similar bent followed. But there was always room at the Voice, as Fancher and Wolf intended from the start, for a broad array of voices in the paper. Writers like Ron Rosenbaum, who became famous for his exploration of pop-culture subjects and figures, joined the Voice from a small Long Island paper when Wolf noticed his writing while he was vacationing on Fire Island. And of course I started writing for the Voice in 1966 while I was a cadet at West Point.

I’ve written about this before, but it bears repeating here. I met the three Voice founders at the annual Christmas party in 1967. I had been writing letters to the editor as a cadet, and Wolf and Fancher sent me an invitation to the party that year. When I was introduced to Mailer and Wolf at the party, they shook my hand and told me they were Infantry veterans of World War II. When I shook Fancher’s hand, he announced that he had served under my grandfather, General Lucian K. Truscott Jr., in the 10th Mountain Division in Italy. To say I was surprised doesn’t do the word justice. At the party were such people as Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, and founder of the off-off Broadway La Mama theater, Ellen Stewart. And there were the three former infantrymen.

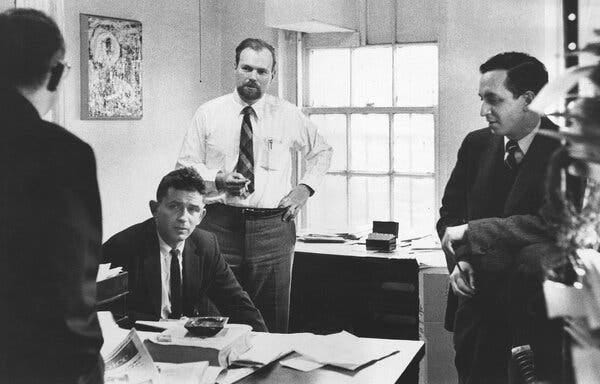

Ed Fancher was a quiet but powerful presence at the Voice. He and Wolf shared an office on the second floor of the Voice offices when they were located on Sheridan Square. At the office on 11th Street and University Place, their offices were next to each other, and I don’t think I was ever in either of their offices when the door between them was shut. Wolf once told me that neither of them made an important decision at the paper without the other. On several occasions when I was assigned to write a story about the Voice itself – when the paper was sued, for example, or when the paper had been challenged by a political figure like Mayor John Lindsay or John Murphy, a congressman who would later be charged in the ABSCAM scandal -- it was Wolf and Fancher both who I met with. They never tried to slant my story, and once or twice I had to interview them during my reporting. It was an example of how they did the important things as a team.

Years later, I gave Ed a copy of the first issue of the Village Voice, which I had taken with me from a basement file cabinet when I quit the paper in 1975 after the paper had been taken over by Clay Felker, who had fired Fancher and Wolf from their positions. I visited him at his apartment at 10th Street and Fifth Avenue, and we sat down in his study to talk about the old days at the Voice. On his wall was a photo of him in his fatigues carrying a rifle standing alongside two other men who were not in uniform. Ed told me the photo was taken after the 10th Mountain Division had taken Riva Ridge in Northern Italy from Nazi forces. The two men standing with Ed were Italian partisans. The three of them had been a scout team that had been assigned to reconnoiter the German positions on top of the mountain before the main attack. Ed and his scout team climbed the sheer cliffs of Riva Ridge at night. His reconnaissance had yielded the information that at night, the German army left its positions overlooking the Po Valley from the top of the ridge and went to sleep in bunkers yards behind the top of the ridge. The 10th Mountain Division launched its surprise attack at night when the Germans thought it wasn’t possible for the Americans to climb the rocky cliff face of Riva Ridge. Ed and his team climbed the cliff twice, once on their scout mission, and once during the main attack. It was the action he was most proud of in the war. There was no war memorabilia in his office other than the photo of Ed and his partisan scout team. Like so many other veterans of the war, including my grandfather, Ed Fancher didn’t talk about his exploits. I had had to visit him in his apartment and be invited into his study to see the photo, and only after I asked about it, did he tell me the story.

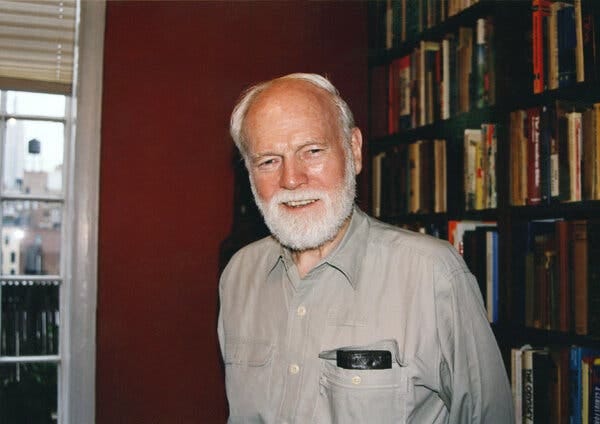

Once in 1971 at a party I gave on the barge where I lived on the Hudson River, someone dosed me with a powerful quantity of LSD, probably delivered by putting it in a beer. The result was one of the worst experiences in my life, a classic “death trip,” during which I recall passing through a red curtain of what appeared to be blood into another world filled with strange hallucinations and images – one of my best friends appeared to me as a devil plotting evil things against me, for example. The party was on a Saturday night, and when I woke up on Sunday afternoon, I was disoriented and frightened and still felt out of my own body. The only person I could think of calling was Ed Fancher. He told me to meet him at his office on West 10th Street as soon as I could get there. A friend drove me, and I arrived to find Ed waiting with the door open at the Brownstone flat where his office was. We sat down and talked for I don’t know how long, it must have been a couple of hours. Ed asked me to tell him what had happened and about the experience. I did the best job that I could, given the fact that I must have been still under the influence of acid. What I remember most about that day was his face. He had the kindest, most open countenance I had ever encountered. I felt safe in his presence. He told me to take a day or two off from work and to eat as much food as I could and drink a lot of water. A few days later, I ran into him on the fifth floor at the Voice where his office was. He smiled at me like he is in the photo below, and I felt like I owed him my life.

I did, in a way. The Voice was the best job I ever had. Writing for the Voice and the men who founded it made me into the writer and man I am today. I feel lucky to have known Ed Fancher. His wife, Vivian, died in 2020. Ed Fancher is survived by his son, Bruce, his daughter, Emily, and two grandchildren. He was a great man.

The Voice was like a (friendly) siren seducing me down into the city where a young boho could freely blossom from where I grew up and was college educated upstate. It was a required weekly read during my over 14 years as a resident of the city. Though my byline didn't appear in the VV until years later (sadly, the New Times ownership years), its influence was still obviously felt at its upstart competition, The Soho Weekly News, where my first significant professional pieces appeared. It was where I learned so much from so many, especially about what a scumbucket grifter Donald Trunp is long before he slimed his way onto the national stage (thanks to the also late, great Wayne Barrett).

So I bow my head in honor to Ed Fancher, impressed that he made it to 100 and by the life he lived. And am thankful, Lucian, that I subscribe and got to read this warm and affectionate tribute to a man who created a groundbreaking paper – I never would have been a Senior Editor/Writer at an alternative newsweekly if there hadn't been a Village Voice, as I see it. So I owe thanks and tribute to Fancher for bettering my life among all the good effects from his life well lived indeed. If there is an afterlife, maybe there's some version there of the Lion's Head where he is now being welcomed and toasted as one of America's great newspapermen.

I love your personal stories about bygone days in NYC. This one is especially moving. Makes me long for that era. It is somewhat comforting to read your comment about writing anything you want today on Substack, just like you did at the Village Voice. We’re fortunate to have you here.