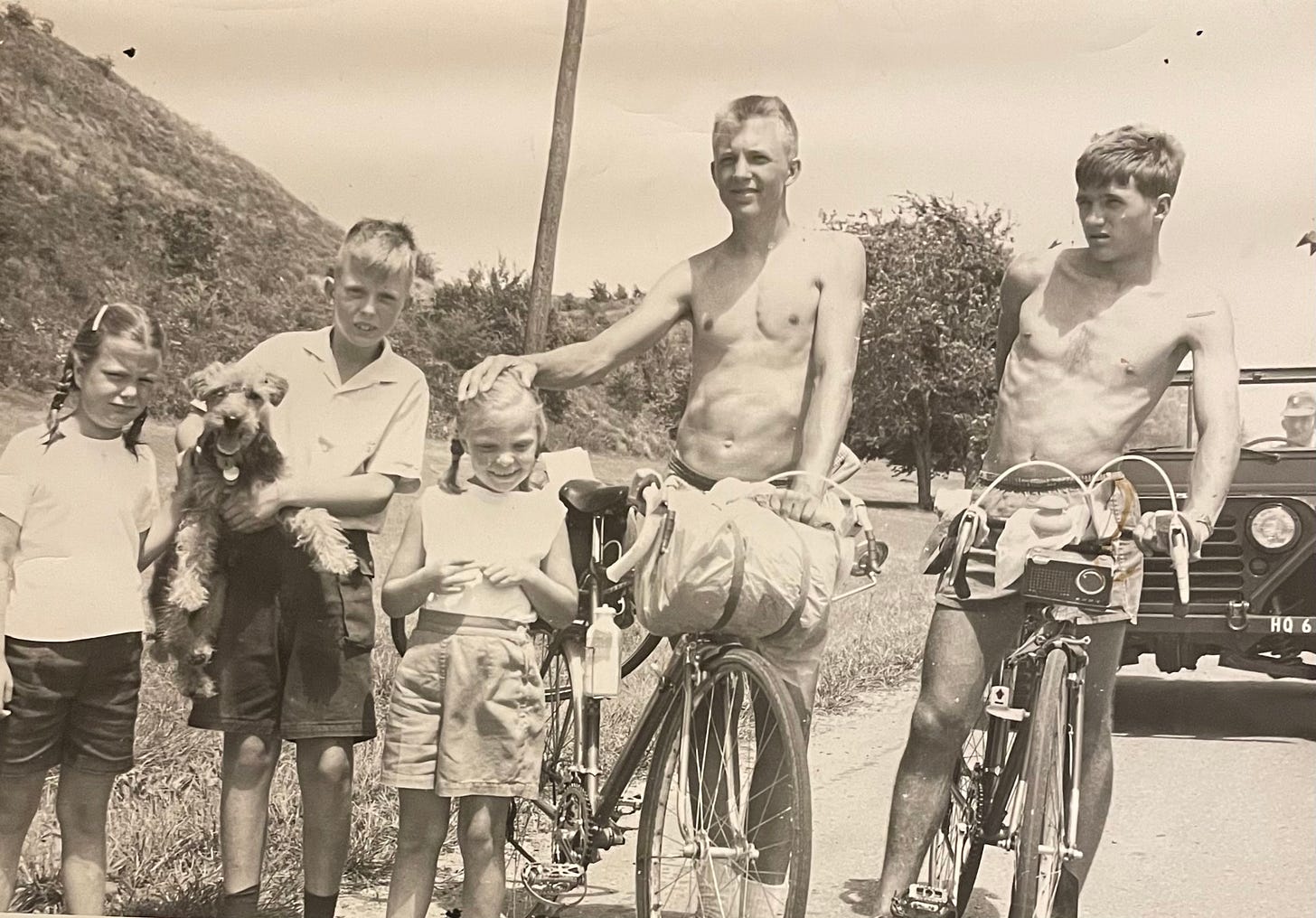

We rode 10-speed bikes halfway across America in 1964.

Fritz Lash and I were 17 years old. That summer changed our lives.

I ate the best breakfast I had ever had somewhere between the towns of Paradise and Gap, Pennsylvania, just off US 30 in June of 1964. My old friend Fritz Lash – and when I say “old friend” I mean it, because Fritz and I had known each other since attending Kindergarten together at Fort Benning in 1953 – and I were riding our 10-speed bikes cross country that summer. We had started in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, where my family was stationed in the Army, and our destination was Fort Riley, Kansas, where Fritz’s family lived.

We began on June the 13th in Carlisle and rode east, headed first for New York City and the hugely hyped World’s Fair. The trip to New York was, in a word, epic. We figured out a way to ride our bikes right into Manhattan by crossing a steel lift bridge over the Arthur Kill River onto Staten Island and then taking the ferry to Manhattan and riding up Trinity Place to Church Street and winding our way over to 6th Avenue up to the 32nd Street YMCA where we stored our bikes in the basement and got rooms for 75 cents a night.

We spent three or four days in the city. The Worlds Fair was a bust – mobs of sweating families dragging kids from one exhibit to another, and Cokes were a then-outrageous 50 cents apiece. We refused to pay that amount and drank from water fountains which were as hard to find as people having fun. Fritz and I had spent our junior years in high school mowing lawns and bagging groceries and in my case washing dishes at the Carlisle Barracks Officer’s Club to earn enough to make the trip. No way were we wasting 50 cents on a Coke.

At least half the reason Fritz and I had organized the bike trip had been because neither of us got along with our fathers. It was my idea to take off for the summer and get away from “the colonels,” as we called them, but how? A kid on the post at Carlisle Barracks had just returned from a posting in England and had a Raleigh 10-speed he had gotten over there. Riding it was like driving a Ferrari, or so I imagined. I talked him into selling it to me, and once had I got a decent price from him, all I had to do was figure out how to sell my parents on the idea.

I waited on a Friday night until my father had had about three martinis, and at the dinner table I announced that I wanted to ride a 10-speed bike with Fritz from Carlisle to New York and the World’s Fair and all the way to Fort Riley. I knew exactly what my half-in-the-bag dad would say: “You’ll never do it. You’ll never earn enough money to pay for a bike and as much as a trip that long would take.” I took a deep breath and challenged him: “Well, if I earn enough for the bike and the trip, will you let me?” He lit up a cigarette and said, “Sure, son! Sure!” and laughed. I wrote about how I’d pulled it off in a letter to Fritz and he followed my script to the letter with his father with the exact same result and the hard part was over.

After paying for our 10-speed bikes – that is what they were called back then, and man were they exotic! – we each had about $200 that had to last us all the way to Kansas. I don’t think we ever sat down and added up the miles, but today using Google Maps and following as closely as I could to the route we took, I found the distance was just under 2,000 miles. With stops here and there along the way, it would take us almost two months.

So back to Manhattan for a few more days, where we discovered the joys of 15 cent rides on the subway, 10 cent pizza slices, and bacon and eggs breakfasts at a luncheonette on 31st Street for a quarter, and Beatnik coffee shops on McDougal Street. It was on that trip I bought my first issue of the Village Voice. The cover story was about the night that one of the first off-off Broadway theaters burned down. It was called Café Cino, and there was a photo by Fred McDarrah of Joe Cino on the front page. I’ve still got it.

We were on our way back through Carlisle when we spent the night in the backyard of an Amish family’s farmhouse along US 30. We carried Army surplus jungle hammocks to sleep in, so around 6 pm every day we started looking at people’s backyards for pairs of trees between which we could sling our hammocks. We settled on the Amish farm because that’s pretty much all there was in that part of Pennsylvania. We knocked on the door – something we would do nearly every night as we rode across the country for the next two months – and asked if we could stay in their backyard, explaining the bit about the trees.

Sure, the man of the house said, and promptly showed us around to the back. We were ready to climb into our hammocks when the Amish farmer showed up and invited us inside for milk and cookies. We spent the next two or three hours telling the whole family – they had seven or eight kids as I recall – about New York City and the World’s Fair and what we’d seen from our bikes along the way. We discovered that the Amish, who didn’t drive automobiles, didn’t travel much, so they wanted to know everything.

The next morning, one of the kids came outside around dawn and woke us up and showed us the way to a wooden trough along which were arranged about a dozen galvanized steel spigots. He handed us two towels and a bar of homemade soap and we washed up alongside the rest of the family. Then they invited us in for the best breakfast of our lives: fried eggs from their chickens, fried ham they had butchered from their own hogs and smoked, thick homemade bread slathered with farm-made butter and homemade strawberry jam and fried potatoes from their underground potato keep. Everything they ate came from the farm. The furniture in the house was Amish made. All the kids wore blue shirts and pants and skirts their mother sewed. Fritz and I ate enough to last us until dinner.

It went like that for weeks. We would wake up at dawn and roll up our hammocks and sometimes the families who let us stay in their backyards fixed us breakfast, sometimes not. On the road we went: Old US 30, the Lincoln Highway and first toll road in America through Pennsylvania, across the Ohio River at Wheeling West Virginia, and onto old US 40, the route we would take for nearly the next month. They were building what would become I-70, the first stretch of the interstate highway system alongside old 40, but other than the Pennsylvania Turnpike, there were no four-lane highways across America, east-west or north-south. US 40 was two-lanes, and it was one of the main east-west trucking routes across the country. Its shoulder, outside the westbound lane, wasn’t much wider than 18 inches, sometimes a little more, sometimes less.

That’s where we rode. Semi-tractor trailer trucks would blow by us doing 60 miles an hour often less than a foot from our left elbows because there wasn’t any room for them to move over if there was traffic coming in the eastbound lane, which there almost always was. We were too inexperienced to search out the state and county roads that could be found slightly north or south of US 40. That’s where cross-country bike riders would ride today, but what did we know? We just stayed on US 40 and went west.

The truckers who drove that route between the coasts, or between cities like Indianapolis and Kansas City, say, passed us going east, turned around and passed us going back west, and a few days later passed us again going east. We were easy to see because we were the only bike riders out there, and we got to know quite a number of them. They would hail us from roadside truck stops and buy us lunch or dinner and ask us how far we’d ridden since they saw us last. Out there in Ohio and Indiana where it was so flat you could see ten miles ahead from your bike seat, we were riding 80 to 100 miles a day.

We had been interviewed by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and their story had been picked up by the AP and spread all over the place, so by the time we hit Columbus, Ohio, the people we asked to sleep in their backyards had read about us, and we got invited in for breakfast more often. We stopped off for Cokes at a Stuckey’s somewhere in Ohio and discovered that the man who owned the famous chain of pecan candy stores had notified all his stores that we were welcome to eat and drink for free! So Stuckey’s became our midday refuel stop whenever we saw one. At some of them, you could even get a hamburger or hot dog.

Midwestern afternoon thunderstorms happened almost daily, so we got wet a lot. But the thunderstorms usually blew through, and we quickly dried in the sun on our bikes. But if it was raining in the early evening when we stopped for the night, we couldn’t hang our hammocks in the rain, so we had to find other lodging, preferably free. I remember pulling into a sheriff’s station in Vandalia, Illinois in a driving rain one night and asking if we could stay in their jail. They’d seen us in the papers, so the sheriff laughed and said, sure, but we had to be in our bunks by 8 pm because they locked down the cells at that hour. The rain let up, and Fritz and I made our way down the street to the library and read for awhile and returned to the jail on time and got locked down. They gave us blankets and pillows and when they clanged shut the cell doors and turned off the lights we were asleep in minutes.

Sometime later, I heard Fritz whispering to me from the next cell to wake up. Groggily, I looked over him through the bars. They had brought in a drunk to sleep it off in the cell on the other side of Fritz. The drunk lit up a cigarette, promptly fell asleep and his blanket was beginning to smolder, so we started yelling for the deputy, who unlocked the drunk’s cell, took his cigarette and matches, thanked us, and we went back to sleep.

During another downpour in Terra Haute, Indiana, the sheriff didn’t have any spare cells, but he directed us to a Lighthouse Mission just down the street. They agreed to give us a bunk for the night but wouldn’t let us in until we had rummaged through their pile of donated clothing and found pairs of trousers to wear, since shorts were decidedly not permitted in the Mission. Fritz and I emerged from a basement room filled nearly to the ceiling with overcoats and suits and whatnot attired in houndstooth woolen suit pants tied to our waists with lengths of clothesline. We discovered that before we would be given dinner and shown to our bunks, we had to shower and attended a fire-and-brimstone church service that went on for over an hour.

It was the shower, however, that I remember best. We stood in line with about 30 road bums who were at the Mission for the night, about half of whom we had run into out on US 40 in our travels. There we were, stark naked with towels over our arms and miniature bars of soap in hand chatting with “Lightnin’ Larry” out of Bangor and “Okie” O’Connor out of Tulsa, listening to their tales of woe about jobs lost, girlfriends who threw them out, and lot-bosses who stole their pay. Then it was my turn. I was given two minutes under a thin stream of luke-warm water, told to towel off, and then a huge bald guy with tattooed arms took one of those old-fashioned bug-spray cans with a long pump and handle and covered me head to toe with white anti-louse powder, hair, “spread your legs” and a shot in the crotch. Fritz came out of the shower and lost it laughing at me. “You look like a ghost!” he said just before the big guy hit him with the stuff.

That night a chorus of snores and coughs from our fellow Lighthouse Missionaires kept waking us up. We left around 4 am at the suggestion of one of the road bums we knew who told us if we waited until wake-up, we’d have to sit through another hour listening to what sinners we were before they’d let us leave.

We didn’t sleep much the night we spent in the hayloft of a farmer’s barn during a deluge somewhere in Missouri either. That night, we were kept awake by scampering rats and the swooping of bats who dive-bombed the swarms of mosquitoes who were feasting on us.

The days, however, were sunny and hot and glorious. Out there in the Midwest you could see the grain elevators and trees of the next town the minute you left the last one. They were always about 10 to 12 miles apart, and we would pass through seven or eight of them, sometimes ten on good days. We’d eat at local diners, where burgers were a dime or 15 cents, a Coke was a nickel, and at night a Blue Plate Special with meat and three or four vegetables and soft rolls and butter and coffee was 75 cents. One day, US 40 ran right alongside I-70 so close we could push our bikes across a field and ride on the unopened superhighway all by ourselves. We thought we were really clever until I-70 veered away from US 40 so far that we couldn’t see it, and the stretch of interstate went on and on, skirting one town we could see but was too far away to push our bikes to. We ran out of water after about an hour on the interstate and had to fill our water bottles from a watering tank next to a big windmill out in the middle of a field. It took another hour to reach an exit that we could take back to US 40 and civilization. I was so glad to see a gas station with an ice-water Coke box, I stood there splashing cold water over myself until the owner came out and asked if we were going to buy one, or not? I think we each bought three nickel Cokes and quaffed them down on the spot.

We reached Fort Leavenworth around the end of July and spent a couple of days at the home of a guy we had gone to George S. Patton Jr. Junior High School with. We lounged around the pool at the officer’s club and basked in the attention of girls who had read about us in the Kansas City Star and the Leavenworth Times. By that point, we had made it a habit to stop in at the local papers in cities we passed through. We made the front page of the second section in Indianapolis and got two pictures and a half page story in the St. Louis Dispatch. Our friend’s mother looked us over when we turned up at their door, recognized the both of us, and exclaimed, “Well, don’t you two look lean and tanned and hardened.”

Indeed we were. By the time we rode into Fort Riley, we had rock-hard thighs and calves and muscled forearms and our hair was lightened from the sun. I spent a few days at Fritz’s house on the post and boxed up my disassembled bike and paid to ship it home to Washington D.C. where my parents had moved over the summer.

I wasn’t in any hurry to get home, so Fritz dropped me off on US 40, and following the tips we had learned from the guys at the Lighthouse Mission, I stuck out my thumb and hitchhiked back to Carlisle. It took a couple of days and sleep was hard to come by, but somehow very late one night I managed to turn up at my girlfriend’s summer cottage in the mountains south of Carlisle. I snuck onto their screen porch and spied a hammock in the dark. By then, I was very, very familiar with hammocks. I was sound asleep when they found me out there in the morning.

For more writing just like this, please subscribe to my newsletter. It’s $60 a year or $5 a month and worth every penny if I do say so myself.

My god, what an epic trip that was! You had the best of all worlds when you could go across country by back roads and live to tell about it.

Damn, it was such a glorious time to be an American.

Thanks for bringing back the times we have lived through.

About the same time you were riding your bike, my parents were taking us on road trips in the west. Just about the only money they spent was for gas. We had one relative in Idaho where we could spend the night. Other than that, we would pull off the side of the road and throw out the blankets and sleep. One morning we woke up to find we were very close to the railroad tracks. Another time, deer were just a stone's throw away. One night the mosquitoes were so bad we packed up and drove farther. We would stop at Safeway every other day or so and buy a loaf of bread and some bologna. Maybe some oranges or apples. One time we passed a farm where they were harvesting peas. We drove in and picked up the bunches that had fallen off the truck. We shelled those peas in the back seat of the car while Daddy drove up the road. We took many trips up through Idaho and Yellowstone and into the Colombia River basin states without spending much money. I don't think people could do that nowadays.