Okay, let’s first dispense with what they call the strategic implications: It’s a defeat. In fact, it is Putin’s third defeat since the beginning of the war. There was the retreat of Russian forces from their positions around Kyiv in late March and early April, and then in September, there was the Ukrainian offensive in the Kharkiv region in the northeast, when Ukraine re-took 7,200 square miles of territory it had lost to the Russians early in the war.

To put it bluntly, it’s not a good look for Vlad the bare-chested macho man, who began the war in February thinking his forces would roll into Kyiv and take a surrender from the Ukrainian government in a matter of weeks. Didn’t happen.

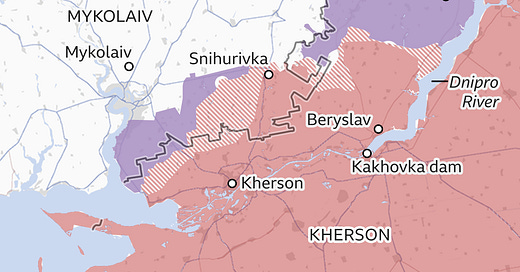

Russia began the war holding a small piece of the Donbas territory in the east, including the regional capitals of Donetsk and Luhansk. Invading from Russian territory in the east and from the Russian held Crimean peninsula, Russian forces over the first several months of the war managed to spread their holdings west from the Donbas, taking most of the Luhansk region, more of the Donetsk region to the south, finally connecting with Russian forces that had invaded from Crimea and had seized most of the Zaporizka region along the sea of Azoz, including the port city of Mariupol. They seized Kherson and connected with their forces in Zaporiska until Russia controlled a corridor stretching from the Russian border in the north and south through Donbas to the Sea of Azoz and the Black Sea at Kherson.

That is where things stand, with Ukraine having retaken a good deal of its territory east of Kharkiv. In the north, Ukraine’s front lines now threaten the city of Donetsk and are moving steadily east toward the city of Luhansk. In the south, of course, Russia has announced its pull-out from the city of Kherson, leaving its forces still holding the corridor through Mariupol and north into the Donbas.

What are they going to do now? They’re going to set up a front line east of Kherson so they can hold the two land-bridges that lead from Ukraine to Crimea and their essential supply lines for their forces in the south of Ukraine. They won’t hold the port of Kherson anymore, but they will still control all of the coast of Ukraine east of there, including the city of Melitopol in the south of the Zaporiska region.

It's useful here to pause for a moment and recall that it was just over a month ago that Russia held its so-called annexation referendums across its entire holdings, including the Kherson, Zaporiska, Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Now Russia is fighting fierce battles to hold its lines across the entire front of the regions it said it had annexed.

Now that we’ve gotten the strategic stuff out of the way, let’s talk about what the retreat from Kherson means to its army. In military terms, a retreat is called a retrograde operation. At the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York; at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia; at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; and at the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania – all of them places where U.S. soldiers are taught tactics and strategy, they teach that a retrograde operation is the most difficult and dangerous thing an army can undertake on the battlefield. There is a simple reason why that is so. You’re going backwards. You’re looking over your shoulder at the enemy, rather than looking at him straight on.

When an army is in retreat, it’s under attack by the enemy. It’s not like the enemy army just stops for a while, so you can pick up your stuff and put your army in reverse. While you’re going backwards, they’re shooting at you. This can cause panic and lead to all kinds of irrational stuff, like leaving your weapons and ammunition behind as you flee backwards.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lucian Truscott Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.