Why artificial intelligence will not take over the world

There is an easy answer to this question, and a hard one. The easy answer is one you read about every time you pick up a paper or read a story in your newsfeed about the building of another one of those gigantic AI data centers that are popping up all over the country. They use more electricity than the towns they’re built next to, is one common complaint you read about. They’re huge; they take up too much land, is another. Google has announced a partnership with a company that will build “energy parks” that will include solar and wind power generation and battery storage facilities. Amazon is building “the largest pipeline of new solar projects of any company in the United States,” according to a solar energy association report.

They are building all these gigantic data storage and processing facilities so that AI companies such as OpenAI, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon and Google can accumulate, store, and distribute the massive amount of data they use to fuel the overall theory behind AI, which is called “scaling.” It is “the idea that training A.I. models on ever more data and using ever more hardware would eventually lead to A.G.I. [Artificial General Intelligence] or even a superintelligence that surpasses humans,” according to a recent New York Times op ed written by Gary Marcus, who the Times describes as “a founder of two A.I. companies and the author of six books on natural and artificial intelligence.”

If what they are trying to achieve is what Marcus calls “superintelligence,” the way they’re doing it is just too damn big: AI data centers the size of 20 football fields consuming the same amount of electricity as a medium size city. As Marcus put it, “Large language models, which power systems like GPT-5, are nothing more than souped-up statistical regurgitation machines, so they will continue to stumble into problems around truth, hallucinations and reasoning.” Because of this, the AI systems currently in use will never “bring us to the holy grail of A.G.I,” which is to build a machine made of electrons, steel and plastic that can think and thereby act like a human brain.

Now, an argument can be made that there will come a day when you can hold all those giant data centers in your hand, in the same way a cell phone has millions times the computing power of an early IBM computer in the 1960’s that took up a room the size of a basketball court. But it’s not just size that AI is having problems with.

This takes us into the second, more difficult part of the answer to the question posed above. Current AI models are essentially Turing machines, based on the theories worked out by Alan Turing, the English mathematician, logician, and theoretical thinker and father of computer science who conceived of the idea of a computer that would use algorithmic and deductive logic in computing the answers to problems. Scaling AI large language systems is based on the idea that by taking in more and more data in the form of human-produced text, an AI system can “learn” from the information it has accumulated.

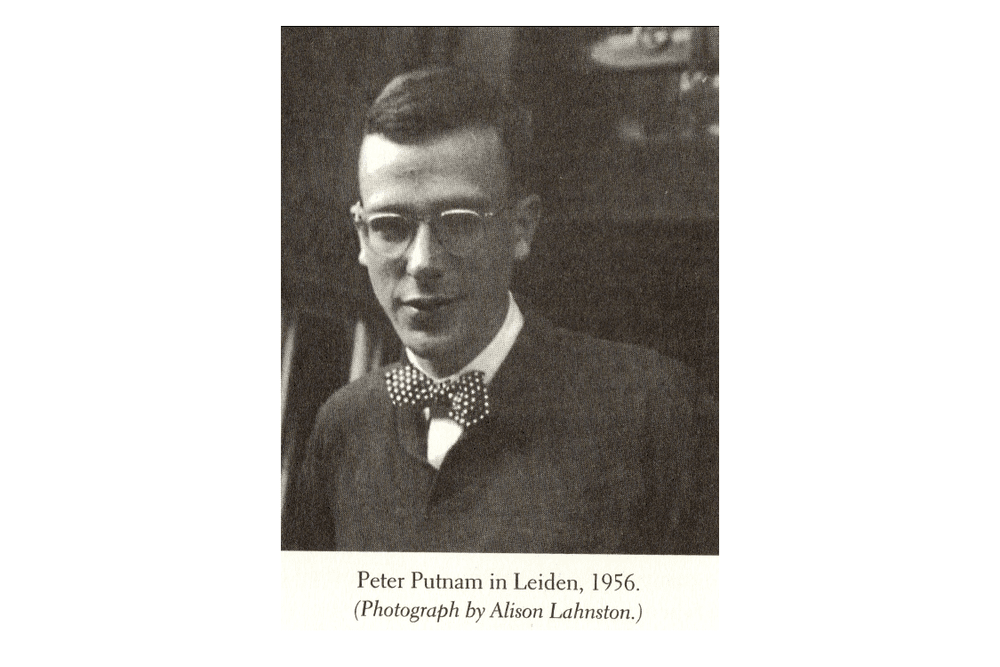

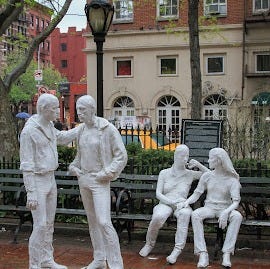

But deductive logic is limited by the information the machine is given. There is an excellent article in the journal Nautilus written by Amanda Gefter that grapples with the theories behind the problem faced by AI. Its title is “Finding Peter Putnam: The forgotten janitor who discovered the logic of the mind.” We’ll get into who the fascinating Putnum is in a moment. Putnam, among other things, donated the George Segal sculpture celebrating the Stonewall uprising in Christopher Street Park in New York City. But it was his contribution to the theories of how the human mind works that set him apart from other philosophers and scientists and put him in the same category of modern computer science as Alan Turing.

“A Turing machine, by design, performs deductive logic—logic where the answers to a problem are contained in its premises,” Gefter writes. Whereas what Putnam was interested in was the logic of induction rather than deduction. “Induction, on the other hand, is the process by which we come up with the premises and rules in the first place. ‘Could there be some indirect way to model or orient the induction process, as we do deductions?’ Putnam asked.” It was, as Gefter writes, the question Putnam asked that put him on the life-long track of trying to understand how the human mind works.

As Putnam saw it, according to Gefter, “In a Turing machine, goals are imposed from the outside. For true induction, the process itself should create its own goals.”

This is a simplification of Putnam’s theories. Gefter spent several years going through two storage lockers containing dozens of filing cabinets filled with Putnam’s unpublished papers, all of them dense with what she came to call “Putnamese,” a complicated scientific language he developed by himself because there was no one he shared his papers with, for whom he might have had to write in a more clear and straightforward fashion so he could be understood.

Putnam was a genius, and a once in a lifetime singular one, according to Gefter. Putnam set out to understand the workings of the human mind – which is essentially what the makers of artificial intelligence set out to replicate – using game theory, which was “thick in the air at Princeton” while Putnam was a student there, according to Gefter. Putnam conceived of the mind as “an induction machine,” a game played within the mind.

“Every game needs a goal,” Gefter writes. “In a Turing machine, goals are imposed from the outside. For true induction, the process itself should create its own goals. And there was a key constraint: Putnam realized that the dynamics he had in mind would only work mathematically if the system had just one goal governing all its behavior.”

“That’s when it hit him: The goal is to repeat. Repetition isn’t a goal that has to be programmed in from the outside; it’s baked into the very nature of things—to exist from one moment to the next is to repeat your existence. ‘This goal function,’ Putnam wrote, ‘appears pre-encoded in the nature of being itself.’”

“The system starts out in a random mix of ‘on’ and ‘off’ states. Its goal is to repeat that state—to stay the same. But in each turn, a perturbation from the environment moves through the system, flipping states, and the system has to emit the right sequence of moves (by forming the right self-reinforcing loops) to alter the environment in such a way that it will perturb the system back to its original state.”

“Putnam’s remarkable claim was that simply by playing this game, the system will learn; its sequences of moves will become increasingly less random. It will create rules for how to behave in a given situation, then automatically root out logical contradictions among those rules, resolving them into better ones. And here’s the weird thing: It’s a game that can never be won. The system never exactly repeats. But in trying to, it does something better. It adapts. It innovates. It performs induction.”

You will notice that within Putnam’s concept of the workings of the mind, there is no introduction of variables from what we might call an outside manager, someone feeding information into the “game,” or the mind, from outside the system. The closest Putnam comes to that sort of introduction is what Gefter calls “a perturbation from the environment” encountered organically from within the system.

Putnam called it “a brain calculus,” explains Gefter. “As the game is played, perturbations from outside—photons hitting the retina, hunger signals rising from the gut—require the brain to emit the right sequence of movements to return to its prior state.”

The brain is accomplishing inference. By trying one thing after another in a never-ending series of repetitions, the brain narrows its calculations. They become less and less random in attempting to return to its resting state, its goal. But the brain isn’t doing this by taking in new information fed to it from the outside. The brain is accomplishing inference from within, by creating for itself new rules of how to play the game by playing the game.

Repetition is the key, and it is not the repetition of searches for new information. It is the repetition of the experience. Resolution is not achieved using right or wrong answers, but by repetition and elimination as the process is narrowed.

The job of artificial intelligence is to produce answers through the deductive process of computing. The job of induction is to create new questions, so that one question can lead to another and another in a process of repetition without answer. That is what “thought” is. It’s not conclusion. It is questing. Induction involves constantly reaching out. Deduction involves constantly taking in, which is why all those data centers are so enormous. They must provide more answers in the form of words to take in for their large language models.

The idea of building metaphorical humans – essentially, robots – began with science fiction, creating worlds that did not really exist peopled by creatures that came from the imagination of the author. Some say Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” was the first science fiction novel, others say science fiction had to wait for H.G. Wells. But the instinct to create what might be called humanness from that which is not human is an ancient one, and we’re still at it. Just look at all those AI data centers out there, trying to create with electrons – all those windmills and solar panels and other means of electrical generation! – and steel and plastic, all those millions of square feet of machines hooked together, and from there, via the internet all the way to…ta-da!...your phone or your laptop. It’s all going into what is sitting on top of your shoulders contained within a flesh and blood skull, the human brain, which in turn contains the human mind.

I urge you to read Gefter’s article in Nautilus, available here: https://nautil.us/finding-peter-putnam-1218035. Putnam is fascinating. He “retired” from science to an apartment in the swamps of Houma, Louisiana, where he worked for the rest of his life as a janitor and nightwatchman for the Department of Transportation, a job he described as “symbolically right.” He used money that he had made before moving to Houma and a small inheritance to invest in the stock market. He made more than $40 million in the market over his lifetime. He and his lover, Claude, whom he had met in Harlem, lived on their earnings, never touching the fortune he had in the bank, all of which he gave away, some of it going to pay for modern art sculptures on the grounds of the Princeton campus and the Segal gay pride sculpture across the street from the Stonewall Inn.

Gary Marcus, in his Times op ed, argues that what AI needs is not “scaling,” the addition of even more words to the large language models that now constitute AI. Instead, he says the next generation of AI will have to involve “the cognitive sciences (including psychology, child development, philosophy of mind and linguistics) [which] teach us that intelligence is about more than mere statistical mimicry.”

In his writings, Putnam refers to the study of how infants learn, beginning with essentially nothing and moving towards inferences from repetitive behavior that build behavior into knowledge. I could have quoted whole pages from both Gefter’s distillation of Putnam and Putnam’s work itself. It is dense, fascinating and essential — all at once.

The men who run the big AI companies would do well to read Peter Putnam and think through what they are doing with all those big buildings and all that electricity they consume. The “answer,” such as it is, to what they are seeking to accomplish may not exist, or it may be simpler than they think.

The tech titans calling the A.I. shots are greedy polar opposites of Putnam.

Thank you for the honors class explication of AI and its forerunners and likely successors. I now have hope in homo sapiens. Many thanks.