It may inform the way you read the closing chapter of this saga to know a few details about how I wrote this story. I got the assignment on a Sunday night from my editor at New Times, John Lombardi. He told me the New York Times and the Daily News and New York Magazine itself all had reporters trying to get the story of how Clay Felker managed to lose his empire. To beat them, we would have to hit the publishing deadline for the next issue, which was a week away on the following Monday.

I reported the story and did all the interviews over the next five days, Monday through Friday. On Friday night, I put up a spare sheet of 4 by 8 plywood next to my desk, and one of the assistants from New Times came down to my loft on Houston Street, and together we outlined the story using notebook pages taped to the plywood board.

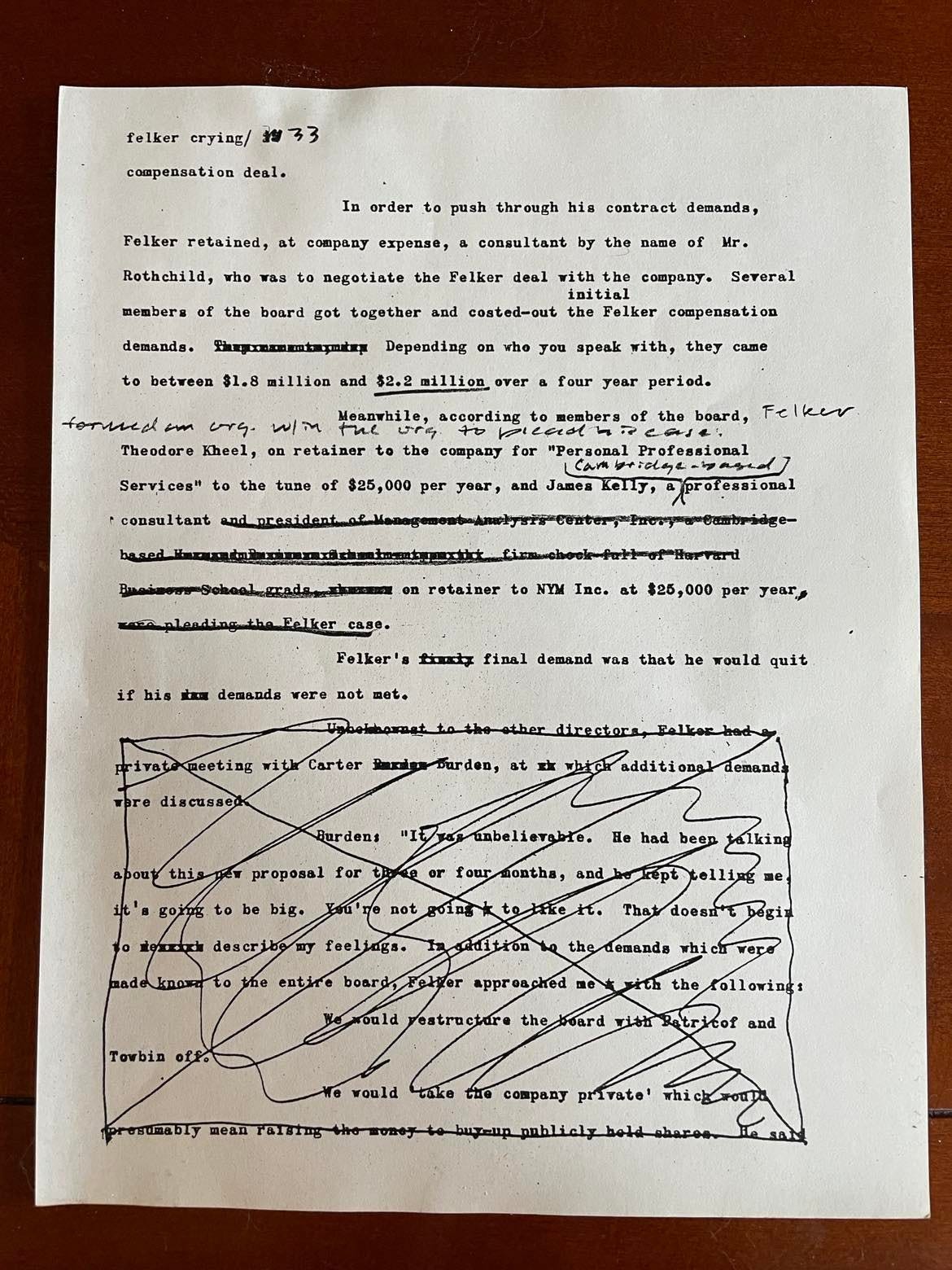

On Saturday morning, I sat down at my rented IBM Model D typewriter and began writing. Around noon, Lombardi showed up and set himself up at the dining room table in the front of the loft. As I produced pages, I would walk them up to Lombardi, and he would edit them. As I looked through the original manuscript, I saw one page with a big penciled X across a third of a page. “Not much left of this one,” Lombardi said, as he lit one of his ever-present Gauloises cigarettes and went back to scratching out words, inserting commas, and making notes in the margins of my pages.

I finished writing the manuscript and Lombardi finished editing it on Sunday night. We repaired to Raoul’s Restaurant on Prince Street for Steak Frites and beers to celebrate. Lombardi took the manuscript home, and it went to the printer in the morning. They had already done the art, and they inserted photos at the printers. It came out that Wednesday. To this day, it’s the quickest 68 page piece I ever cranked out for anyone.

We pick up the story a few days before the deal went down. Going back through the manuscript, I figured out that from beginning to end, it took Murdoch just 49 days to take over the New York Magazine empire.

Part Three

December 22: Lawyer and NYM Inc. board member Peter Tufo lunches at Clay Felker’s duplex apartment on East 57th Street. He represents board member Carter Burden and his 24 percent of NYM Inc. stock. He tells Felker that Murdoch has offered $7 a share for Burden’s stock, and that Burden is actively considering the offer. Tufo says he wants to give Clay a chance to counter the Murdoch offer, and it’s obvious that if Burden sells 24 percent of the company, Felker has lost.

Felker’s first response, according to a sworn affidavit from Tufo: “He can have it.” (italics in the original document) Felker maintained in an interview with me that he made no such statement.

Then, according to Tufo, Felker said he wanted time to work out a deal that would give him 51 percent of the company without Burden’s stock. “Fine,” said Tufo. “Go ahead.” Burden had not made up his mind about Murdoch’s offer and asked for 10 days to think things over.

Felker recalled: “I made my position clear, and I’ll stick by it. Burden is a goddamn incompetent little dilettante.”

That afternoon, Felker begins to make some moves. Murdoch: “Felker rang me up – it must have been right after he had lunch with Tufo – and he was incredibly abusive. He was in the New York Magazine bullpen in the office. I could hear people around him over the phone. He wanted an audience, and he was really giving it to me. ‘I’ll sue you, I’ll finish you in this town.’ He was making all kinds of threats. Then suddenly, after two or three minutes of this abuse, he quieted down and was completely rational. He began telling me about his problems with the Voice. He said he had ‘completely lost a sense of what the paper is.’ The most recent issues had been the worst in the paper’s history, he said. Then suddenly he’s screaming at me again, threatening lawsuits, and I said, ‘Look, Clay, Shuman and I are serious, but we haven’t made up our minds. I’ll get back to you.’”

December 23: Peter Tufo calls Burden in Sun Valley and says Murdoch has agreed to hold off and give Burden time to make up his mind.

December 24: Burden calls Felker at the New York Magazine offices and fails to reach him. Burden tries him at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, the Beverly Hills Hotel, and finally calls the Lyford Cay Club in Nassau, Bahamas. No Felker.

Felker was in fact in Nassau staying at David Frost’s house. I asked him why he left New York in the middle of a firestorm that might cause him to lose his company. “I felt protected by my rights of first refusal clause over Carter Burden’s stock. I don’t know how to explain it to you. I just felt protected, that’s all.”

Rupert Murdoch, meanwhile, feeling another kind of protection, is in New York City at his Fifth Avenue duplex.

December 27: Burden reaches Felker in Nassau. The phone connection from Sun Valley, Idaho to Nassau, Bahamas isn’t good, but Burden finally gets through and explains to Felker that Murdoch’s offer is real, and that because Murdoch has promised to buy out all the other shareholders at the same price he offered Burden, Felker will have to come up with the same kind of deal.

According to Burden, Felker explodes: “You’re going to be charged with selling out two New York publications! You’re going to be the target of a huge publicity and legal battle! If I were you, I wouldn’t want to take on Dick Reeves (author and NY Magazine writer Richard Reeves), let alone Clay Felker!”

Felker denies yelling at Burden and calls the conversation “friendly,” although he admits that he “told Carter a lot of people are going to be mad at him.”

December 29: Kay Graham, owner of the Washington Post, is prepared to buy Carter Burden’s shares, or so Clay Felker believes. Felker calls Burden and tells him he is glad that “we can finally be friends,” and tells him he will have an offer for his shares by December 31.

Burden recalls the conversation completely differently: “He didn’t tell me he was involved with Kay Graham and the Washington Post in any way.” Perplexed, Burden hung up and called his lawyer, Peter Tufo and asked him what was going on. He didn’t know any more than Burden did.

December 30: Burden gets a call from Tufo, who has spoken to investment banker Felix Rohatyn, who is representing the Washington Post. Rohatyn explains that the Post’s offer would dissolve NYM Inc. and make it a division of Newsweek, which the Post owns. Tufo tells Burden there would be no continuing role for him on the board of NYM Inc., which would be folded into Newsweek, or with Newsweek itself.

In an interview, Burden tells me that he picked up the phone and called Murdoch, whose offer for his 24 percent of the company was still on the table. “Murdoch said, ‘Felker is no friend of yours. Did you know he was up all of last night negotiating a new contract for himself with the Washington Post?’ There it was. Clay and his contract again. So I called Clay and I said, ‘Look, you’ve claimed for 18 months that you wanted control of NYM Inc, and now you’re selling out the whole company to go to work for the Washington Post?’ Felker started screaming: ‘You have to accept the Post offer tomorrow! If you don’t, there will be no magazine left to sell! I’m going to turn the entire New York journalism community against you!’ The irony here is that at that point, I hadn’t really made up my mind.”

December 31: Rohatyn strides into Tufo’s office and bids $7.50 a share for Burden’s stock on behalf of the Washington Post. Tufo picks up the phone and calls Murdoch, who betters the offer.

Told that Murdoch has topped the offer by the Post, Felker picks up the phone and calls Sir James Goldsmith, a brash ultra-conservative London financier who is looking to get into publishing. But Goldsmith presents Felker with a serious problem. He is politically far to the Right, and in the last 12 months had filed 100 writs of libel against the satirical London biweekly, Private Eye, a British record. To the extent that Private Eye is a muckraking, scandal-mongering tabloid, it is to London what The Village Voice is to New York.

I asked Felker later why he would even think of turning to such a character. “He would have gone to $8.50, he might have even gone to $9 a share. I was scrambling, that’s all.”

January 1, 1977: Felker somehow obtains a temporary restraining order (TRO) in Federal District Court barring the sale of Burden’s stock to Murdoch, pending the outcome of whatever legal action he can come up with.

What Felker didn’t know, or forgot, was that at midnight on December 31, 1976, the fourth quarter results for NYM Inc. were official. The company had lost money for four straight quarters in a row. According to the stockholders’ agreement, the consecutive four-quarters loss had nullified the right of first refusal contract Felker had over Burden’s stock.

Later on New Years Day, Tufo, Shuman and Murdoch fly to Sun Valley, Idaho. Upon landing, someone informs them that the TRO had been issued back in New York, but because none of them had been served, they decide to ignore it and go through with the deal.

At 9 p.m. over a table in a Sun Valley restaurant, Burden signs the papers transferring his stock in NYM Inc. to Murdoch, who promptly signs a check for $3.5 million and passes it across the table to Burden. “Let me see it! I’ve never seen a check for three and a half million dollars!” says Susan Thompson, Burden’s “frequent companion.”

January 2: By that evening, Rupert Murdoch owns outright or has signed contracts giving him control of 51 percent of NYM Inc. stock. “We didn’t have to go after the other stockholders,” Stanley Shuman recalled later. “They came to us. Not one of them wanted to stand by Clay.”

That night, Murdoch phones Kay Graham, informing her that he now controls NYM Inc.

“We had kept up a warm but occasional friendship over the years,” Murdoch recalled as the clock in his duplex living room struck 12 on the night of our interview. “Once she gave a dinner for me and invited Henry Kissinger. Another time, I visited her at her country home, and Felker was there. It was ‘Clay said this’ and ‘Clay said that.’ Every time Clay would suggest something, she’d pick up the phone and call Ben Bradlee (the editor of the Washington Post who famously oversaw its coverage of Watergate by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein). She would relay Clay’s suggestion. You could almost feel the hostility coming back over the line from Bradlee every time she mentioned Felker’s name.”

Murdoch’s wife called from the top of the stairs in the living room for him to come up and help her get the children back to sleep. The interview had woken them up. He disappeared for a few minutes and came back downstairs, collapsing into his armchair.

“When I told Kay, she was very, very emotional. ‘I wanted to buy it [NYM Inc.] for my Clay,’ she kept saying. ‘You’ve taken it away from my Clay. You’re going to ruin his life’s work. All the writers will leave.’ She was sobbing, just sobbing over the phone. I had rung up to make peace, to tell her I hoped our friendship could survive. I could hardly believe how emotional she was.”

That same evening, Robert Towbin, another NYM Inc. board member and stockholder, called Graham to tell her he was selling his stock to Murdoch. (Towbin’s 1.5 percent put Murdoch over the 51 percent threshold.) In an interview, Towbin shook his head in amazement as he recounted the conversation: “She was crying, and all she could talk about was how we were ruining ‘my Clay.’ The only thing I could conclude was that the woman was in love with Felker.”

Stanley Shuman confirmed what Murdoch had told me: “She [Kay Graham] was willing to go to $7.50, maybe higher, but all her advisers were against it. Felker was making the same contractual demands on the Washington Post that had alienated his own board of directors.”

January 3: After a tumultuous board meeting to install Murdoch and Shuman on the board, Felker retreats to the New York offices looking for the support he couldn’t get from the men who owned his company.

January 4: The staff of New York Magazine issues a press release denouncing Murdoch on “moral” grounds, supporting Felker, and threatening to walk out if Murdoch takes over. But Murdoch had already taken over, and the principal spokesmen for the staff, political writers Richard Reeves and Ken Auletta, did not bother to inform themselves that Felker had only a month before been negotiating with Murdoch in a fruitless attempt to sell both New York and The Village Voice in return for a controlling interest in New West. Nor did the staff spokesmen bother to learn about Felker’s approach to the right-wing king of libel-suits, Jimmy Goldsmith.

January 7: After a staff work stoppage at New York Magazine, Felker sells 10 percent of the company to Rupert Murdoch for $1.2 million.

Later, Murdoch reflected on the mistakes Felker had made that enabled him to grab Felker’s empire:

“What Clay never realized was the simple fact that there are ways to deal with a board of directors. He could have had them to lunch twice a year at the offices of New York with the governor or Teddy Kennedy or somebody. He could have flown them all to the West Coast for the founding of New West, given them a dinner at the Beverly Wilshire and introduced them as ‘my colleagues and friends.’ With a few little moves, he could have kept them happy. Instead, he made enemies of them, one by one. In Clay’s eyes, they were all threats to his authority. I guess in a way, he was afraid of them.”

When it was all over, Clay Felker left for a 10-day vacation on an island in the West Indies. Felker’s loyalists, who quit the magazine to protest Murdoch’s takeover, stayed in New York and moved over to his duplex apartment on 57th Street with the promise of working for him in the future. They continued to answer his phone with the words, “Clay Felker’s office,” but it was his home phone.

It truly was the end of an era.

Editorial note: When my New Times story came out, lawyers for Kay Graham called the editor and publisher of the magazine and denied that Ms. Graham had cried on the phone with either Rupert Murdoch or Robert Towbin. They threatened to sue the magazine if a correction wasn’t issued. Later the same day, the magazine received hand-delivered letters from Murdoch and Towbin denying they had said that Kay Graham had cried over her friend’s loss of his company. They threatened to sue, too.

The editor and publisher of New Times called me with their denials and asked me to come to the office to discuss the response to the lawsuit threats. I produced my notebook showing the exact quotes I wrote down during both interviews and pointed out that of all the stuff we had printed about the Murdoch takeover, Kay Graham crying was the only thing they said I got wrong. I told them they could do whatever they wanted, but I wasn’t going to issue a personal correction or apology.

They settled with publishing letters to the editor from Murdoch, and Towbin denying they had said anything about Kay Graham crying. The editor issued a statement in the same letters column saying that New Times stood by its story.

They asked me if I wanted to reply to the denials in the letters, and I declined. The editor asked me why I didn’t want to issue my own denial. I answered, “They got two lines in the letters column. I got 9,000 words in the magazine. I think readers of New Times can make up their own minds who they believe.”

'Sensational' is probably too 'tabloid' a word to describe your article, but damn... that was good.

When we discussed this at the time New Times published it you told me you'd caught the principals at the brief peak moment for revelation. They'd just had time to digest what had happened and were still open before inevitably clamming up.

I forget what the final court proceeding was to seal the deal. A formality—neither Murdoch or Felker was in the room where that happened, but I was. (Kevin McAuliffe reported that in his VV history.) Felker had trashed my world and I wanted to see his around his ankles.

You mentioned.his admission he and Glaser had lost their way with the Voice. I know exactly what went wrong. The Voice had been a newspaper from first issue to Dan Wolf's last. Felker understood only magazines, and tried to turn the Voice into one. From his first post-Wolf paper, he traded immediacy for sensation. The Voice was never the Voice after Felker switched from having a news photos+bylined news/features front page, to a kaboom! Glaser-era cover. Newspapers have front pages, magazines have covers; they never got the difterence.